Humanity has already flung machines into interstellar space, but sending people is a different problem entirely. The physics of propulsion, the fragility of the human body, and the sheer size of the solar system combine to make crewed escape feel less like a delayed milestone and more like a fundamental limit. If we ever do leave our stellar neighborhood, it may be as data and machines, not as flesh and blood explorers.

That is not for lack of ambition. From early rocketry to today’s Mars plans, each generation has assumed the next breakthrough would finally unlock the stars. Instead, the closer researchers look at the engineering, biology, and economics, the more it seems that no matter how hard we try, our species may be effectively confined to the Sun’s domain.

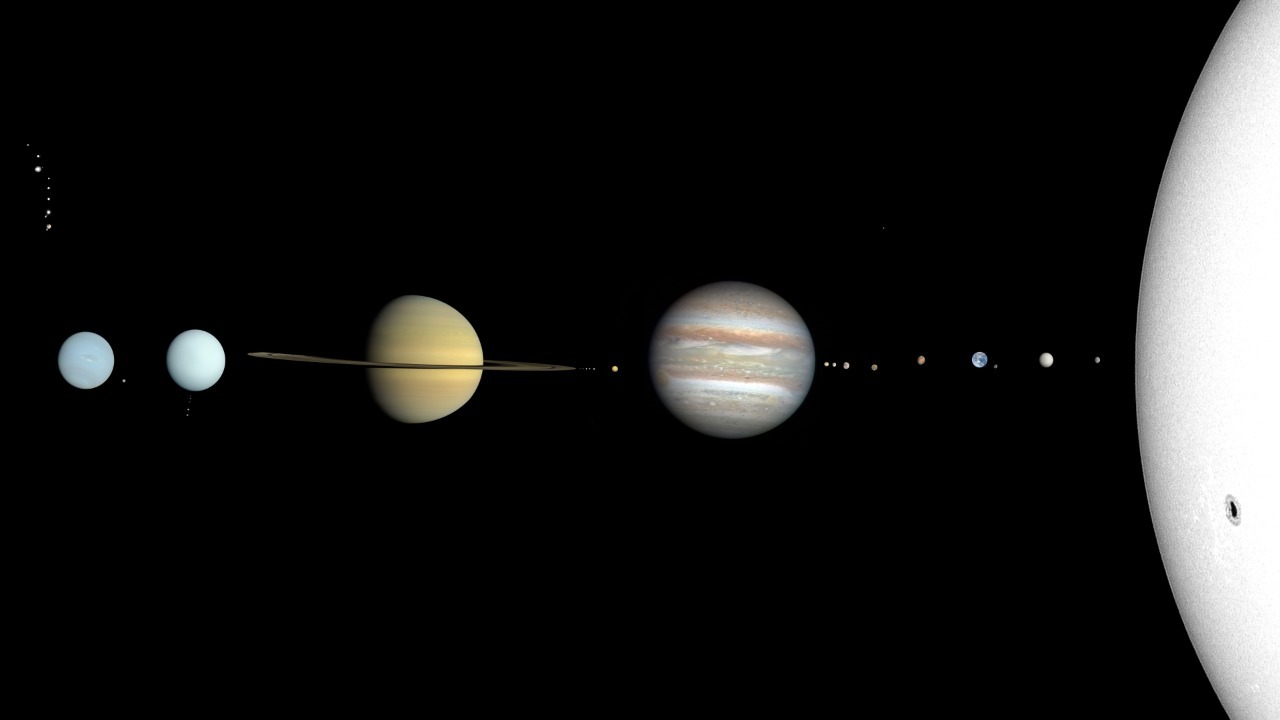

The solar system is bigger, and harsher, than it looks

Escaping the solar system sounds simple on paper: build a faster rocket and keep going. In practice, even defining where the system ends is tricky. Probes like Voyager have crossed the heliopause, where the Sun’s wind gives way to interstellar plasma, yet they still face the vast shell of icy bodies called the Oort Cloud that may extend for light years before true interstellar space begins. Even at tens of thousands of kilometers per hour, a spacecraft can spend tens of thousands of years threading that distant haze.

Closer in, the basic act of leaving Earth is already a monumental hurdle. As one spaceflight primer notes, Challenge number one is simply Getting to Orbit, climbing out of the deep gravitational well that locks us to the planet. That same gravity shapes the entire solar system, binding comets in the distant Oort Cloud and making “escape” a matter of accumulating enormous kinetic energy, not just pointing a ship at the stars.

Physics punishes any attempt at star‑hopping

Once a spacecraft is free of Earth, the real problem begins: interstellar distances turn even aggressive propulsion concepts into centuries long cruises. Interstellar travel between stars is not just a matter of going farther, it is a regime where relativistic effects, collision hazards, and energy demands dominate the design. A knowledge of the properties of interstellar space shows that even sparse gas and dust become dangerous at high fractions of light speed, because each grain hits with the force of a bomb and would be much more destructive than at orbital velocities.

Rocket equations add another layer of difficulty. As one technical discussion on Answers puts it, the biggest issue, apart from the sheer distance, is that any conventional rocket must carry its own reaction mass, and that requirement explodes as you aim for higher speeds. In that exchange, the consensus is that Manned interstellar space flight is not going to happen anytime soon and Definitely not within the next 50 years, because no plausible fuel can deliver the required delta‑v without turning the ship into a flying fuel tank.

Even if exotic drives solved the mass problem, high speed itself becomes a threat. A recent analysis of relativistic missions notes that near Earth, the growing cloud of artificial satellites already complicates safe trajectories, and at interstellar velocities, tiny particles pose lethal risks to any hull. Another study of the limits of exploration puts it bluntly: Unfortunately, current spacecraft technologies simply cannot traverse such astronomical distances in feasible time frames, especially with fragile human passengers on board.

The human body is not built for deep space

Even if propulsion were solved, biology might still strand us near home. Humans are not built for space, and our bodies are tuned to Earth gravity, atmosphere, and magnetic shielding. Long missions already cause severe physiological damage, from bone loss and muscle atrophy to immune changes and vision problems, and those effects compound over months and years. Medical reviews of With the emergence of space tourism describe how microgravity disrupts cardiovascular function, fluid distribution, and even cellular processes, turning every system into a potential failure point on a long voyage.

Radiation is even harder to engineer away. Outside Earth’s magnetic cocoon, astronauts face a constant storm of high energy particles that damage tissue and DNA. One overview of long duration missions highlights the Radiation risks that appear as soon as crews leave the protective zone, noting that highly energetic particles can penetrate most shielding and that hybrid approaches to mitigation are still experimental. Another assessment of why Human bodies really cannot handle space points out that Spaceflight damages DNA, alters the microbiome, and disrupts circadian rhythms over the long term, suggesting that multi decade journeys would push human physiology far beyond tested limits.

Even ambitious countermeasures underline how extreme the problem is. One space medicine specialist describes how Muscles weaken, bones thin, and cardiac strain grows on the way to Mars, prompting proposals for induced hibernation to slow metabolism and preserve organs. Another explainer on astronaut health stresses that Our bodies evolved over millions of years to function optimally in Earth’s environment, with gravity and atmospheric pressure as non‑negotiable inputs. If we struggle to keep crews healthy on a months long trip to Mars, the idea of surviving centuries in a starship begins to look less like engineering and more like biology fiction.

Economics and psychology quietly close the door

Beyond physics and biology, there is the question of why anyone would pay for a journey that no one can return from. One detailed essay on the sheer vastness of space argues that distance divides ambitions into modest interplanetary projects and almost unreachable interstellar ones, with the latter demanding resources that could transform life on Earth instead. In a more personal reflection, the writer Jul notes that it would be extremely expensive to send a crew beyond the solar system and that even if some volunteers like James would sign up, the mission would still only move a tiny number of people off world, leaving the rest of humanity behind.

Psychology compounds the cost problem. Generational “space arks” are often proposed as a workaround, but even optimistic scenarios admit that Even the nearest star system, Proxima Centauri, lies more than four light years away and that Current propulsion concepts would require enormous energy costs and substantial risks just to keep a closed city alive for centuries. A popular video essay on why we may never escape the solar system points out that in recent years we have managed to land on the Moon and send probes to Mars, yet those triumphs still sit firmly inside the Sun’s gravitational bubble, with no clear economic case for pushing further.

Why “never” might still leave room for robots

When people talk about being trapped in a “cosmic bubble,” they are usually thinking about human crews, not machines. A widely viewed explainer on why it is so difficult to get out of the solar system asks whether we are effectively stuck in our little cosmic bubble and then walks through the colossal challenges that stand in the way, from propulsion to life support, before conceding that uncrewed probes face far fewer constraints. Another video on why it is so hard to leave, released in Jun, similarly contrasts historic achievements with the dreams of interstellar travel, arguing that robots can tolerate the slow, hazardous journeys that humans cannot.

That distinction matters for how I read the word “never.” Technical reviews of Challenges of Interstellar Travel The challenges associated with reaching “Earth 2.0” emphasize that the obstacles test the limits of human ingenuity and technological prowess, but they also imply that machines, not people, are the likely pathfinders. As long as physics, biology, and economics line up the way they do today, I suspect “never” will apply to crewed escape from the solar system, while swarms of robotic scouts quietly slip into the dark beyond the Oort Cloud.

More from Morning Overview