In a set of experiments that has jolted a notoriously grim field, researchers in Spain report that a carefully calibrated trio of drugs wiped out pancreatic tumors in mice and prevented them from growing back. The work targets the same molecular circuitry that drives most human pancreatic cancers, raising the prospect that a similar strategy could one day change the outlook for a disease that is usually lethal within months of diagnosis. I see it as a proof of principle that the right combination, aimed at the right weak points, can turn even this cancer’s entrenched biology against itself.

The findings come from a team led by cancer biologist Mariano Barbacid at Spain’s National Cancer Research Center, which has spent years dissecting how pancreatic tumors depend on a single mutated gene and its downstream signaling network. By hitting three critical links in that chain at once, the group reports complete tumor clearance in mice with no signs of resistance, a result that has quickly drawn global attention and cautious hope among clinicians and patients alike.

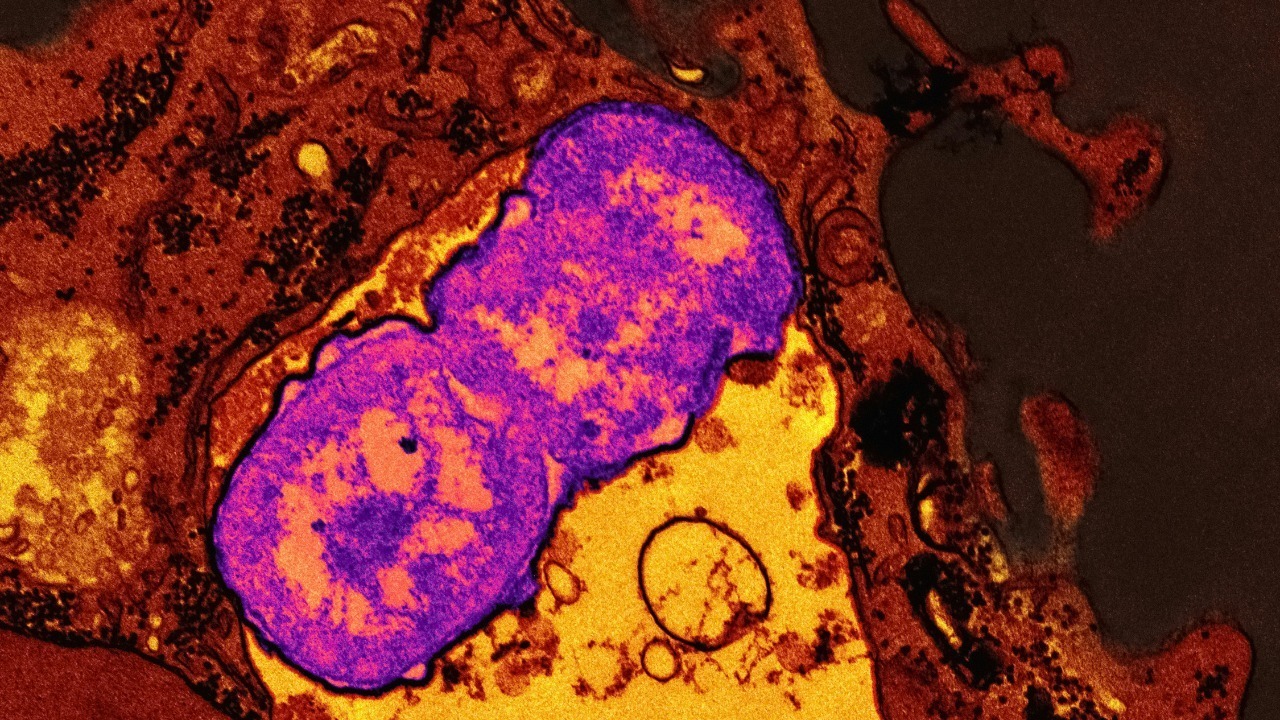

How a Spanish team erased tumors in mice

The Barbacid group focused on pancreatic tumors driven by mutant KRAS, a gene that acts like a stuck accelerator pedal in many cancers. In their latest work, the researchers used a triple combination that blocks KRAS itself and two of the main signaling routes it uses to keep tumor cells alive, essentially cutting power to the cancer’s growth engine at three separate switches. In genetically engineered mice that spontaneously develop pancreatic tumors, this strategy led to complete disappearance of the cancers and no detectable regrowth over the course of the study, according to the center’s detailed report on pancreatic tumours.

What makes this especially striking is that the tumors did not seem to find a workaround, a common problem when a single drug is used against a single target. The researchers describe “no resistance developing” in the treated mice, suggesting that simultaneously shutting down three KRAS-dependent pathways leaves the cancer with nowhere to go. The same report notes that the group is now looking at how to translate this approach into treatments that can be given to people, a step that will require identifying or refining drugs that can safely block the KRAS molecule and its key signaling partners in human tissue.

What “triple therapy” actually targets

Pancreatic cancer has long been defined by its resistance to standard chemotherapy and radiation, so the logic behind this triple therapy matters as much as the headline result. Instead of relying on a single blockbuster drug, the Spanish team designed a combination that interferes with three distinct but cooperating signals that KRAS uses to drive tumor growth and survival. Reports on the work describe a regimen that targets three “links in the chain” of KRAS signaling, a phrase that captures how the drugs are meant to interrupt the flow of growth commands from the mutated gene down through the cell’s machinery, as outlined in the center’s explanation of targeting three nodes.

Other researchers have been pursuing similar multi-pronged strategies, including combinations that enlist the immune system. Earlier work on pancreatic tumors in mice found that pairing PD-1 inhibitors, which release a brake on T cells, with TIGIT inhibitors, which block another immune checkpoint, produced stronger responses than either drug alone. In that study, scientists began testing whether PD-1 and TIGIT inhibitors together could do what each drug could not achieve on its own, an approach described in detail in a report on Following this discovery. The Spanish triple therapy fits into this broader shift toward combination regimens that attack pancreatic cancer on multiple fronts, whether by cutting off its growth signals, unmasking it to the immune system, or both.

Why the mouse cure is not yet a human cure

For all the excitement, I have to stress that curing cancer in mice is not the same as curing it in people. The animals in the Barbacid study were bred to develop tumors in a controlled way, and their treatment was carefully timed and monitored, conditions that rarely exist in real-world clinics. Reporting on the work notes that the therapy completely eliminated pancreatic tumors in mice, but also emphasizes that the new approach is still a potential breakthrough rather than a proven treatment for patients, a distinction highlighted in coverage of the Spanish findings.

Translating the regimen into human trials will require solving several hard problems at once. The drugs used in mice may not behave the same way in human bodies, and hitting three powerful signaling pathways at once raises the risk of serious side effects in organs that rely on the same signals for normal function. Researchers involved in the work have acknowledged that applying the same strategy in patients will mean searching for drugs that can block KRAS and its downstream routes with enough precision to spare healthy tissue, a challenge that is already shaping early discussions of how and when to test the triple therapy in people, as reflected in the center’s comments on Applying the approach beyond the lab.

Global reaction and parallel breakthroughs

The response to the Spanish data has been swift, in part because pancreatic cancer remains one of the deadliest malignancies worldwide. A social media post from Jan described how researchers in Spain had achieved a triple combination that cleared pancreatic tumors in mice, calling it fresh hope in the fight against a cancer that usually kills within a year of diagnosis, a sentiment captured in a widely shared summary of work from Spain. Another account described how scientists in Spain used a medical treatment known as triple therapy to cure pancreatic cancer in mice, underscoring that the work could represent a major advance if it translates to humans, as noted in a concise explainer on Scientists using this approach.

Officials have taken notice as well. The Embassy of Spain in the UK publicly highlighted the achievement, describing it as a major breakthrough that could make a difference for one of the most lethal cancers if future trials confirm the benefit, a point emphasized in coverage citing Embassy of Spain. At the same time, other laboratories are reporting complementary advances, including work from Stanford researchers who developed a lab-made molecule that, when paired with paclitaxel, wiped out aggressive breast and pancreatic cancer in preclinical tests, as described in a detailed note on Stanford. Taken together, these developments suggest that the field is finally starting to crack some of the biological defenses that have made pancreatic tumors so hard to treat.

What comes next for patients and trials

For patients and families living with pancreatic cancer today, the obvious question is how soon any of this might change their options. Scientists involved in the Spanish work have been careful to describe the triple therapy as a significant advance in research rather than an immediate cure, stressing that the mouse results must be validated in carefully designed human studies. One detailed account notes that the therapy works by blocking signals that promote tumor growth and that the next step is to test whether similar combinations can safely shut down those signals in people, a cautionary note that appears in a report quoting Scientists involved in the study.

More from Morning Overview