The common cold is so ubiquitous that it feels like background noise, yet for a subset of people it is a wrecking ball that triggers weeks of misery or even dangerous complications. The same respiratory viruses that barely slow one person can send another to urgent care, and that gap is not just bad luck. It reflects a layered mix of viral behavior, immune wiring, genetics, age, and environment that tilts the odds long before a cough starts.

When I look at why some people sail through infections while others are flattened, the pattern that emerges is not a single “weak immune system” but a series of small advantages and vulnerabilities that stack up. From the cells lining the nose to inherited variants in immune genes and the chronic conditions that shape our defenses over decades, the story of who gets crushed by a common virus is really a story about how unevenly our bodies share the burden of everyday pathogens.

Why a “common” cold is anything but simple

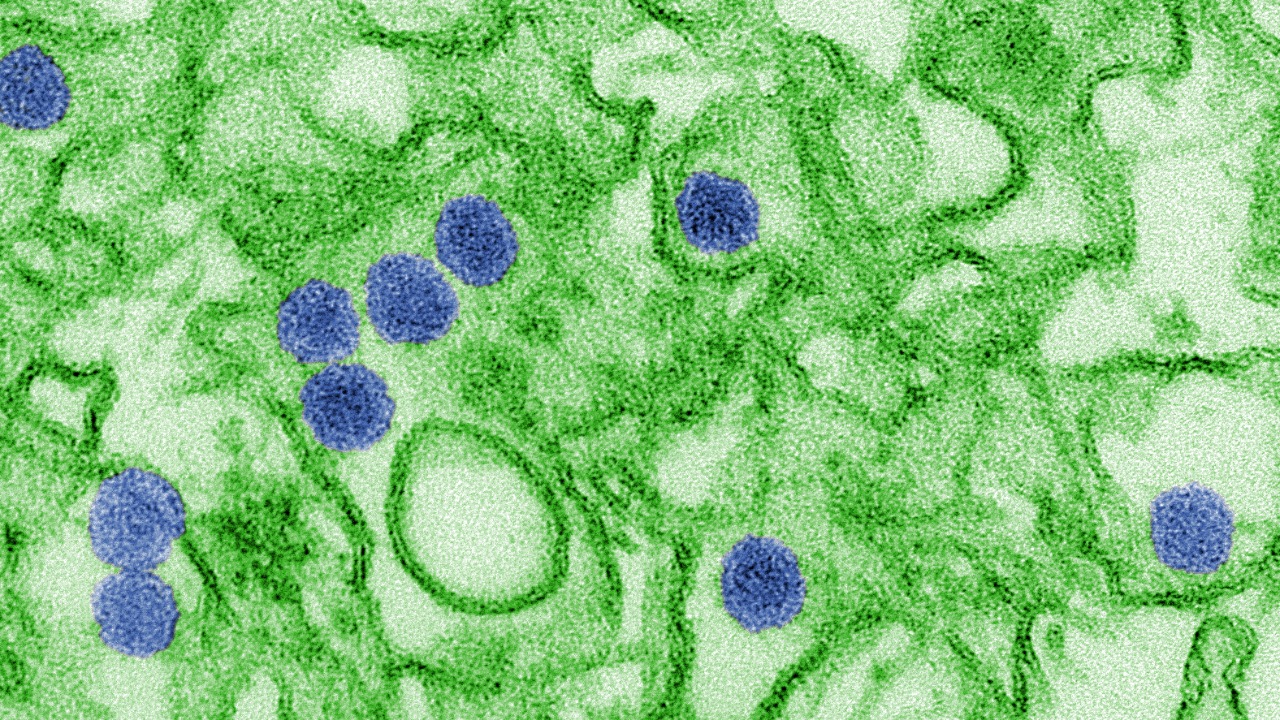

On paper, the common cold looks straightforward: a short, self limited infection with runny nose, sore throat, and fatigue. In reality, it is a cluster of different viruses that exploit the same real estate in the upper airways, which is why experts describe it as a unique human disease with a huge variety of causative agents and symptom patterns. Detailed reviews of the common cold emphasize that rhinoviruses dominate, but coronaviruses, adenoviruses, and others also contribute, each interacting differently with the host’s immune system.

Those interactions matter because cold symptoms are not just a direct effect of viral damage, they are the result of a dynamic tug of war between viral traits and host responses. Analyses of cold symptoms show that the same infection can be trivial in one person yet trigger severe, even fatal, complications in another when inflammation spills into the lower airways or aggravates existing disease. That variability is the first clue that the virus itself is only half the story.

The nose as frontline: why some infections never take off

Before a virus ever reaches the lungs, it has to get past the nose, which turns out to be a surprisingly sophisticated gatekeeper. Earlier this year, researchers reported that nasal cells coordinate an early defense against rhinovirus, releasing antiviral molecules and recruiting neighboring cells into a collective shield. In that work, Scientists found that the robustness of this first response could determine whether the virus is contained quickly or allowed to spread, suggesting that some people’s noses are simply better prepared for battle.

That frontline performance is shaped by age, prior exposures, and the local ecosystem of microbes that live in the nasal passages. One study of the nasal microbiome, which sampled the noses of 152 people, found that certain bacterial communities were linked to more intense cold symptoms, hinting that resident microbes can either help train the immune system or leave it off balance. When I put those findings together, the picture that emerges is that some infections are blunted at the door, while others are effectively invited in by a less responsive or poorly tuned nasal environment.

Genetic wiring and ancestry: who is primed for severe disease

Once a virus gets past the surface, inherited differences in immune genes start to matter. Large analyses of severe viral infections have identified specific variants that change how efficiently people detect viral RNA, produce interferons, or regulate inflammatory cascades. In one Abstract focused on host genetics, the Background section notes that Susceptibility to severe viral infections has been tied to variants that alter inflammasome activation and the risk of a cytokine storm, the runaway immune reaction that can turn a routine infection into a crisis.

Those variants are not distributed evenly across populations, which is where ancestry comes in. Work on how our genetic ancestry shapes responses to influenza has highlighted that Susceptibility to infectious disease is one of the strongest evolutionary pressures on humans, and that One of the key findings is that immune pathways have been tuned differently in distinct ancestral groups. When I look at those data, I see a reminder that “normal” immune responses are not a single standard but a spectrum shaped by generations of viral encounters, which helps explain why the same respiratory virus can produce very different patterns of severity across families and communities.

Age, sex, and underlying conditions: the slow forces that tilt the odds

Beyond genes, the slow march of time and the presence of chronic disease quietly reshape our vulnerability to everyday viruses. Detailed epidemiology of the Common cold shows that Age patterns are striking, with young children experiencing frequent infections and older adults facing higher risks of complications as immune memory and lung resilience change. Public health guidance on risk factors underscores that Some groups of people have higher chances of getting very sick from respiratory viruses, including those with heart disease, chronic lung disease, or weakened immune systems, because their baseline reserves are already stretched.

Sex differences add another layer. Immunology work summarized under the heading Evidence shows that men and women respond differently to infection because different parts of their immune systems are enhanced, and Age is also a factor in how those differences play out over a lifetime. That pattern shows up clearly in more severe infections too: analyses of the novel coronavirus causing COVID found that people with conditions such as diabetes and chronic lung disease were far more likely to die, even when exposed to the same viral dose. When I connect those dots back to the “common” cold, it becomes clear that a virus that is trivial for a healthy 25 year old can be a serious threat for an older adult with COPD or heart failure.

Immune history, lifestyle, and the new era of overlapping viruses

How often someone gets sick, and how hard, is also shaped by the immune history they carry into each season. Clinicians who study why some people seem to catch every bug point to differences in sleep, stress, nutrition, and chronic inflammation that can blunt immune responses. A related Introduction to this topic notes that Some individuals have immune systems that are either overactive or underactive, and that understanding those patterns can benefit overall well-being by guiding targeted lifestyle changes. At the population level, experts on the tripledemic of COVID, RSV, and flu have warned that Some scientists use the phrase “immunity gap” to describe how reduced exposure during lockdowns left susceptible people, especially young children, with fewer antibodies against flu and other airborne pathogens, setting the stage for more intense waves once restrictions lifted.

Vaccination and prior infections also recalibrate risk, particularly for influenza. Official guidance on People at risk stresses that Anyone can get flu, and that serious problems can happen at any age, but it singles out older adults, pregnant people, and children younger than five years as especially vulnerable. That mirrors what detailed reviews of the Abstract on the common cold have found: the first infections in early childhood are often the roughest, and subsequent colds are usually milder after several infections as immune memory builds. When I step back from all of this, the pattern is stark. The virus may be common, but the terrain it lands on is anything but uniform, shaped by genetics, age, chronic disease, lifestyle, and a lifetime of prior encounters that together decide who shrugs off a sniffle and who ends up fighting for breath.

More from Morning Overview