In a quiet corner of a physics building in Australia, a glass funnel filled with a tar-like substance has been dripping so slowly that only nine drops have ever fallen. As it approaches its centenary, this deceptively simple setup is on track to mark 100 years of continuous operation, making it the world’s longest running laboratory experiment. I see in this strange, patient device a rare window into how science can stretch across generations, challenging our sense of time, attention and even what counts as a “result.”

How a lump of tar became the world’s slowest experiment

The story begins at the University of Queensland in Australia, where physicist Thomas Parnell set out to prove a simple point to his students: some materials that seem solid can, over long periods, behave like very slow liquids. In 1927 he heated a sample of pitch, a petroleum derivative used for waterproofing, and poured it into a sealed glass funnel, then left it to cool and harden. Once the pitch had solidified, he cut the funnel’s stem and placed a beaker underneath, inviting future observers to wait and see whether the “solid” would ever flow.

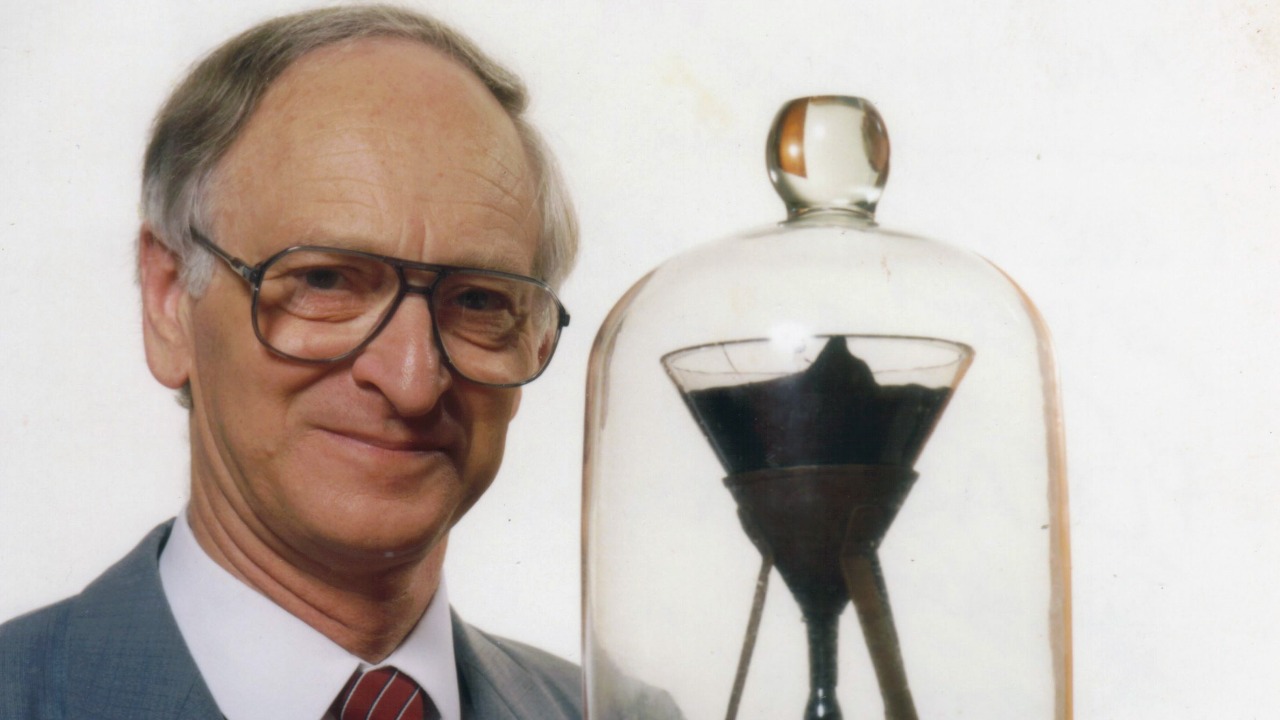

That modest classroom demonstration has since been recognised as Pitch Drop Experiment, officially listed as the Longest running laboratory experiment in the world. The apparatus, now housed on the St Lucia campus, still contains the original pitch sample prepared by the university’s first physics professor, Thomas Parnell, and it has been allowed to run essentially undisturbed for decades. What began as a teaching aid has become a living piece of scientific history, quietly stretching across the careers of multiple generations of physicists.

What the Pitch Drop actually shows

At first glance, the pitch in the funnel looks like a black, glassy rock, which is exactly why Parnell chose it. The point was to confront students with the idea that everyday intuition about solids and liquids can be misleading, and that time is a crucial variable in physics. Over years, the pitch slowly deforms under its own weight, creeping through the funnel’s stem until a bulbous droplet forms and, eventually, detaches into the beaker below. It is a direct, visual demonstration that pitch is a highly viscous fluid rather than a true solid.

Researchers at the School of Mathematics estimate that the pitch in the funnel is many orders of magnitude more viscous than water, so it flows extraordinarily slowly. To date, only nine drops have fallen in the famous Pitch Drop experiment, with the last one recorded in the 2010s and another expected sometime this decade. That glacial pace is precisely the lesson: materials like pitch, which seem rigid at human timescales, can exhibit quite surprising properties when observed over spans that approach a century.

A century of drips, and almost no one saw them

One of the strangest aspects of this experiment is that, for most of its life, nobody actually witnessed a drop fall. It took about eight years for the first droplet to finally hit the beaker, and subsequent drops have arrived at a cadence of roughly once every eight to thirteen years. Earlier this decade, coverage noted that the world’s longest continuously running lab setup was still going and about to turn 100, yet despite the global attention, the crucial moment of each drip has remained elusive.

Modern technology has tried to close that gap. The experiment is now monitored by a webcam at the St Lucia campus so that anyone can watch the funnel online, although technical problems prevented one of the drops around November 2000 from being recorded. According to the Pitch Drop experiment entry, the camera streams the apparatus in real time, turning a once obscure teaching aid into a minor internet curiosity. Even so, the odds of being logged in at the exact second a drop detaches are slim, which only adds to the mystique.

From cupboard curiosity to Guinness World Record

For years, the apparatus sat largely ignored in a cupboard of the physics department, its slow progress noted only occasionally by staff. Over time, as more drops accumulated in the beaker, the experiment’s age and continuity began to stand out. Accounts of the Pitch Drop Experiment describe how it gradually shifted from a forgotten demonstration to a celebrated symbol of patience in science, especially once the early drops were tallied and the timescales involved became clear.

Recognition eventually came in the form of a formal record. The Guinness World Record for longest continuous running experiment goes to the pitch drop experiment, which has run since 1927 at the University of Queensland. A university note on Guinness World Record this setup highlights that nine drops have fallen so far, with the last falling in 2014. Guinness itself lists the Pitch Drop Experiment at the University of Queensland as the Longest running laboratory experiment and notes that it could easily run for another hundred years if left undisturbed.

Why scientists still care about a 100‑year drip

It is tempting to treat the Pitch Drop as a quirky museum piece, but physicists still see value in what it represents. The experiment is a vivid example of viscosity at extremes, showing how a material can be billions of times thicker than water yet still flow. Reporting on the world’s longest running lab setup has pointed out that the pitch sample is so resistant to motion that it behaves as if it were solid, even though, at the molecular level, it is slowly rearranging itself. One analysis described the pitch as many orders of magnitude more viscous than water, a figure echoed in coverage that calls it the world’s longest running lab experiment.

There is also a cultural and educational dimension. A social media explainer on This 100‑Year‑Old Science experiment notes that no one has ever seen a drop fall in person, yet the setup continues to fascinate students and visitors who encounter it. It is a rare case where the absence of a dramatic moment is itself the lesson: science is often about careful observation over timescales that dwarf a single human attention span. In an era of instant results, the Pitch Drop quietly insists that some questions can only be answered by waiting.

More from Morning Overview