The first humans walked on the Moon more than half a century ago, yet a stubborn minority still insists the whole thing was staged on a soundstage. Polls and surveys in the United States and Europe show that disbelief in Apollo has become a durable feature of modern conspiracy culture rather than a passing fad. To understand why, I have to look past the physics and photography and into the mix of politics, psychology and online storytelling that keeps the hoax narrative alive.

The political stakes that seeded suspicion

From the start, the Moon landings were entangled with power and prestige, which made them ripe for doubt. During the Cold War, the United States treated Apollo as a high‑stakes demonstration that its technology and system could outpace the Soviet Union, and NASA ultimately raised about US$30 billion to reach the Moon, a scale of investment that critics like Kaysing later pointed to as motive for fakery. In that telling, an agency under pressure to beat Moscow and justify vast spending might have found it easier to fake success than risk failure in front of the world, even though the actual Apollo budget, totaling US$25.4 billion between 1960 and 1973, is well documented in NASA records.

That geopolitical backdrop still shapes how hoax believers frame their case. Popular explainers on why some people think the United States did not really land on the Moon describe a narrative in which NASA and the U.S. government supposedly orchestrated a deception to win the propaganda war, with the Moon program cast as a secret weapon in the Cold War and a way to prove the United States had the better technology. In this view, the question is not whether the rockets could work but whether a government locked in rivalry during the Cold War and space race could be trusted to tell the truth about its most symbolic victory.

How a handful of “anomalies” became canon

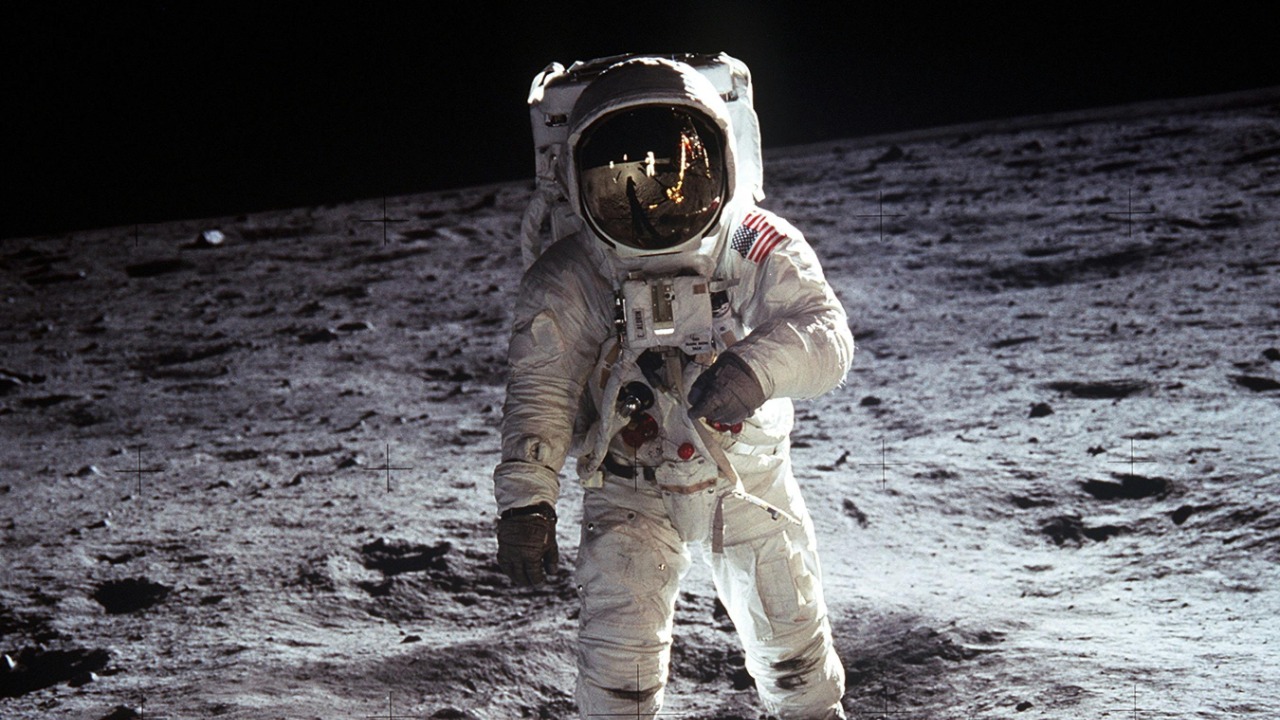

For most Americans, the televised Apollo missions were a shared national memory, but from almost the point of the first Apollo flights a small group of Americans began insisting they had never taken place at all. Early hoax books and TV specials elevated a short list of supposed photographic and physical anomalies, and those talking points have barely changed since, even as experts have answered them in detail. One influential critique argued that images of Buzz Aldrin saluting the U.S. flag on the Moon showed impossible motion in the fabric, a claim that engineers and historians have repeatedly debunked by pointing to the specially designed flagpole and the physics of movement in a vacuum, as detailed in analyses of Buzz Aldrin footage.

Other familiar claims focus on missing stars, odd shadows and lethal radiation. A critical review of hoax arguments notes that one of the most prominent talking points is the absence of stars in Apollo photos, even though cameras set for bright lunar terrain would not capture the dim light of distant stars, a point laid out in a detailed Critical Examination of. Lists of “top” Apollo conspiracies also highlight claims that multiple‑angle shadows in surface images prove there was more than one light source, when in reality uneven ground and perspective can produce shadows of many different lengths and directions, as explained in breakdowns of The Shadow Knows and similar claims.

Radiation belts, flags and other “gotcha” science

Technical‑sounding objections give the hoax narrative a veneer of expertise that can be persuasive to non‑specialists. One widely shared argument insists that The Van Allen Radiation Belts Would Have Killed Them, framing the belts as an impenetrable wall that would have made lunar travel lethal for Apollo crews. Detailed rebuttals point out that the spacecraft trajectories, shielding and limited time spent in the highest radiation zones kept doses well below fatal levels, but the phrase “Few arguments feel as technical or as frightening” captures why this line of attack resonates in discussions of Van Allen Radiation.

Visual “gotchas” are even more accessible. Conspiracy Theory lists often start with the idea that The American flag is waving in the wind, even though there is no air on the Moon, and then build out a catalog of supposed impossibilities. Engineers respond that the flag was a specially designed flag with a horizontal bar to hold it out, and that any motion came from the astronauts’ handling, not a breeze, a point that careful Explanation pieces walk through frame by frame. Similar compilations of space myths note that Some of the questions moon landing deniers ask, such as “Why are there no stars in the sky?” or “Why are the U.S. flags moving?”, rest on misunderstandings of cameras, lighting and physics, even as they are recycled in lists of Some of the biggest space conspiracies.

Polls, mistrust and the psychology of doubt

Despite the scientific answers, disbelief has become surprisingly common. Research starters on Moon landing conspiracy theories note that such ideas emerged shortly after the Apollo 11 mission and that opinion polls in the United States have tracked a persistent minority who say the landings never happened, even as the technical evidence has grown. A separate survey in Europe found that In February and March researchers asked people in France, Germany, Hungary and Italy, among other countries, about various conspiratorial claims and reported that 25% of Europeans said the Moon landing never happened, linking that response to an established history of conspiracy thinking in the region, according to a survey of attitudes.

Psychologists point to deeper motives behind those numbers. Reviews of Motivational and Social Factors argue that Epistemic Motives, such as a desire for certainty in a complex world, can drive people toward simple, all‑explaining stories when reality feels messy or threatening. One honors essay on the topic describes how Mistrust and Existential Motivations When analyzing the data emerge as common themes, with believers often expressing a general suspicion of institutions and a need to feel they possess hidden knowledge, patterns echoed in Mistrust and Existential researchers interview them. Experimental work at Johannes Gutenberg University in Germany similarly finds that belief in conspiracy theories is stronger among people who say they want to feel special and who are more likely to reject authorities and the status quo, a pattern highlighted in a study from Johannes Gutenberg University in Germany.

The internet, community and why the hoax story will not die

Digital culture has turned what was once a fringe belief into a constantly refreshed storyline. Communication researchers note that Moon landing conspiracy theories emerged in the wake of Apollo but have persisted in the popular imagination because modern media ecosystems make it easy to share and remix claims, even when experts show that a widespread deception is highly improbable, a point underlined in Moon focused research. Commentators who track these narratives argue that the hoax claim should not spread on merit, since the evidence cited by deniers is, in every single case, ridiculous, yet they warn that the Moon‑hoax conspiracy may grow as social networks reward provocative content and as distrust of institutions deepens, a concern raised by historian Launius.

Online, the hoax narrative is not just a set of claims but a community. On Reddit, a Former Aerospace engineering student patiently explains to skeptics that it is exponentially easier to go to the Moon with rockets than to fake every detail convincingly, yet the thread itself shows how persistent the doubts remain, as users on Former Aerospace forums trade links and memes. Educational videos walk viewers through why some people claim the Moon landing was faked, replaying the moment Buzz Aldrin did land on the moon on July 20th 1969 and then unpacking how selective frames, Including misinterpreted audio and grainy stills, are used to sow doubt in clips such as Including. Other explainers show how one of the main kind of arguments that conspiracy theorists have used, from flag motion to studio lighting, falls apart under scrutiny, as presenters in Jan debunking videos methodically address each point.

More from Morning Overview