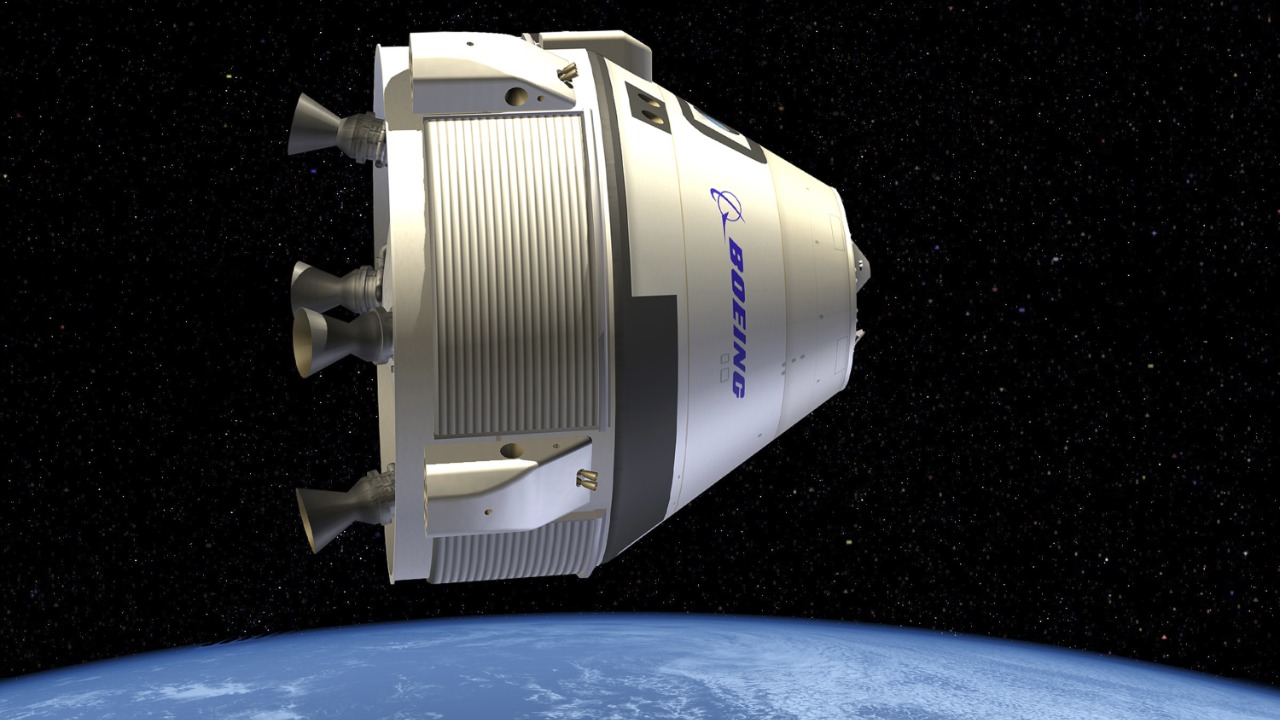

Boeing’s Starliner capsule is about to face the kind of trial that can redefine a program’s future. After years of delays, cost overruns, and technical surprises, the spacecraft’s next outing will fly without astronauts, turning a planned crew rotation into a cargo-only mission that doubles as a high-stakes engineering exam. Whether Starliner clears that bar will shape not only Boeing’s role in low Earth orbit, but also how much redundancy NASA can really count on for access to the International Space Station.

Instead of showcasing a mature crew vehicle, the upcoming Starliner-1 flight will be a carefully constrained test, focused on proving that the capsule’s propulsion and plumbing can be trusted before anyone straps in again. I see this pivot as a rare moment of candor in human spaceflight: an admission that the hardware is not yet ready for routine astronaut service, and that one more uncrewed dress rehearsal is the price of keeping Boeing in the game.

The quiet downgrade from crewed debut to cargo test

Starliner-1 was originally pitched as the spacecraft’s first regular crew rotation, a four person ride to the ISS that would finally put Boeing on equal footing with its commercial rival. Instead, NASA and Boeing have now formally recast that mission as a cargo-only flight, with no astronauts on board and a launch target no earlier than October 2026. The shift, confirmed in a program update, turns what was supposed to be a milestone into a remedial exam, signaling that the agency is not yet prepared to trust Starliner with routine human transport.

The decision did not come out of nowhere. Earlier planning had assumed that, after its crewed test flight, Starliner would quickly transition into operational service, flying four person crews to the ISS on a regular cadence. Instead, NASA officials used a Monday briefing to make it official that Starliner-1 will carry only cargo to the station, with the new schedule explicitly framed as “no earlier than October 2026” in the same announcement. For a vehicle that was supposed to be a co-equal pillar of NASA’s crew access, that is a sobering reset.

Technical demons: thrusters, helium, and “dissimilar redundancy”

The cargo-only plan is not just about optics, it is about specific hardware that has to prove itself under flight conditions. The Starliner-1 mission will be used to wring out the capsule’s “doghouse” thruster assemblies, the helium plumbing that feeds them, and a set of procedures that were refined after earlier anomalies. NASA and Boeing have framed this as a chance to validate the propulsion system in a lower risk configuration, with the cargo mission explicitly tasked to test those thrusters and plumbing as part of a broader push for what engineers call “dissimilar redundancy” in crew transport. That focus was underscored in reporting that described Starliner-1 as a pivotal cargo mission designed to exercise the doghouse thrusters, helium lines, and related procedures before anyone flies on them again.

From my perspective, this is the clearest sign that Starliner’s problems are not just paperwork or software, but physical systems that need more real world data. Thrusters and helium plumbing sit at the heart of any capsule’s ability to maneuver, dock, and, in an emergency, abort. By turning Starliner-1 into a cargo mission, NASA is effectively buying itself one more full up test of those systems while keeping astronauts off the risk curve. If the doghouse assemblies and helium network behave as designed, the agency can argue that it has restored confidence in the capsule’s propulsion. If they do not, the consequences for Boeing’s human spaceflight ambitions will be severe.

From flagship partner to over-budget question mark

When NASA selected Boeing for its commercial crew program, the company was supposed to be the safe bet. Over a decade ago, NASA agreed to pay billions of dollars for Starliner flights to and from the International Space Station, expecting that a legacy aerospace giant would deliver a robust second option alongside SpaceX. That original vision, described in detail in a retrospective, now sits uncomfortably next to the reality of a capsule that still is not ready to carry NASA astronauts on its next flight.

The financial picture is just as stark. Starliner is already more than $2 billion over budget, a figure that reflects redesigns, rework, and the cost of repeated test campaigns. NASA and Boeing have both stressed that they are continuing to rigorously test the Starliner program, but the same reporting that highlighted the budget overrun also noted that the next mission is rated cargo only, not crew. That combination, captured in an analysis of how Starliner is already, turns the cargo-only flight into a referendum on whether that investment can still be justified.

NASA’s redundancy problem in a SpaceX dominated era

For NASA, the stakes go beyond one contractor’s balance sheet. The agency’s commercial crew strategy was built on the idea of dissimilar redundancy, with two very different spacecraft providing independent paths to orbit so that a problem with one would not ground all crew access to the ISS. In practice, SpaceX’s Crew Dragon has become the workhorse, while Starliner has struggled to reach operational status. The cargo-only Starliner-1 mission is therefore not just a test of hardware, it is a test of whether NASA can still credibly claim to have two functioning crew systems in the medium term.

The contrast is sharpened by the cadence of other launch providers. SpaceX, for example, regularly advertises backup launch opportunities down to the minute, such as a Saturday window at 6:41 pm EDT that was promoted with the reminder that “Please be advised that all launch times are subject” to change. That level of routine scheduling, captured in a note about a, highlights how normalized crew and cargo flights have become for one provider while Boeing is still working to certify basic systems. If Starliner-1 succeeds, NASA can argue that it is finally on the path to restoring the redundancy it has long promised. If it falters, the agency will remain heavily dependent on a single commercial partner for human access to the ISS.

Why this cargo flight is a make-or-break moment for Boeing

All of this is why I see the upcoming cargo-only mission as a make-or-break test for Boeing’s role in human spaceflight. The company has already absorbed reputational hits from delays and cost overruns, and it now faces a binary outcome. A clean Starliner-1 flight, with doghouse thrusters, helium plumbing, and docking operations performing as designed, would give NASA the technical basis to proceed toward crewed rotations and would help justify the billions already spent. A troubled mission, by contrast, would raise hard questions about whether the agency should keep pouring resources into a capsule that still cannot fly astronauts safely.

There is also a broader industry signal at stake. If Boeing can turn Starliner-1 into a quiet success, it will show that traditional aerospace contractors can still recover from early missteps and compete in a market increasingly shaped by faster moving rivals. If it cannot, the cargo-only downgrade will look less like a prudent safety step and more like the first step toward winding down a troubled program. With NASA, Boeing, and the ISS all tied to the outcome, the next Starliner launch will be far more than a simple cargo run, it will be a verdict on whether this spacecraft has a future beyond being an expensive cautionary tale.

More from Morning Overview