Microbes that hitched a ride into orbit are not just surviving in space, they are changing in ways that give them startling new abilities. In the strange physics of microgravity, bacteria and viruses are mutating into forms that can cling harder, resist stress and, in one striking case, attack pathogens that normally shrug them off. Those same adaptations that make space microbes formidable could, if handled carefully, become powerful tools for medicine on Earth.

What sounds like the premise of a disaster movie is instead emerging as a disciplined research frontier. From the International Space Station to China’s Tiangong outpost and even NASA cleanrooms, scientists are watching microbes evolve in real time and then reverse engineering their tricks. I see a pattern taking shape: space is turning into a kind of accelerated evolution lab, and the most shocking “new power” these organisms are gaining is the ability to outthink our antibiotic crisis.

Microgravity as an evolutionary pressure cooker

In orbit, microbes encounter a physical environment that biology on Earth never prepared them for. Fluid barely stirs, nutrients drift instead of flowing, and cells experience constant radiation and confinement. Experiments on the International Space Station show that these conditions push bacteria and viruses into evolutionary corners they would rarely explore on the ground, forcing them to rewire how they grow, stick to surfaces and interact with hosts, as documented in work on microbes mutated in. Instead of the well-mixed flasks of a typical lab, microgravity creates a patchy, low-mixing world where only the most adaptable strains thrive.

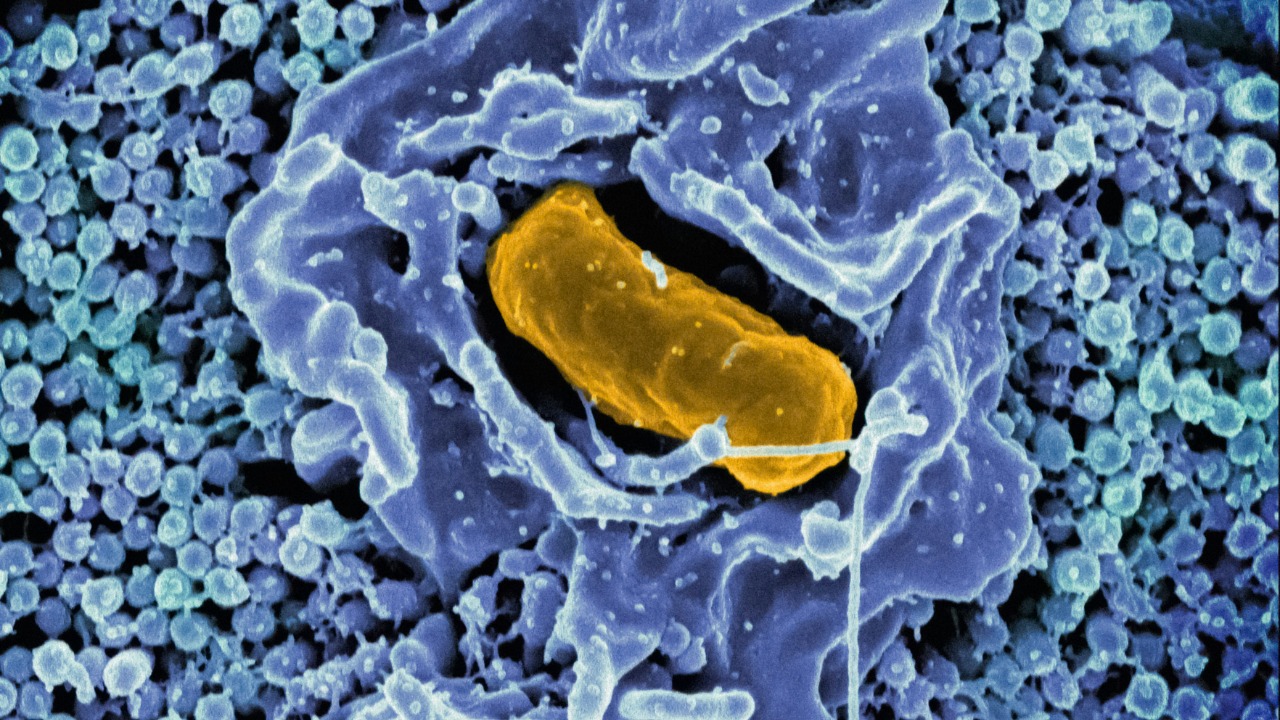

That shift is not just theoretical. Researchers studying bacteriophages, the viruses that infect bacteria, have shown that the physical characteristics of microgravity, including reduced fluid convection and altered bacterial physiology, reshape how a phage finds and infects its target. In orbit, the T7 phage and its Escherichia coli host coevolve under these constraints, with the virus adapting to a host that itself is changing in response to spaceflight, a dynamic captured in work on microgravity coevolution. I see that as the core of the story: space is not just a harsh backdrop, it is an active sculptor of microbial evolution.

ISS bacteria are mutating into functionally distinct strains

Nowhere is that sculpting clearer than on the International Space Station, where long term occupants include more than just astronauts. Investigations funded by Ames Space Biology have found that multi drug resistant bacteria on station surfaces are mutating into forms that are functionally distinct from their Earth relatives, according to Principal Investigator Dr Kasthuri Venkateswaran of NASA at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. These microbes are not just picking up random mutations; they are shifting traits in ways that appear to help them cope with microgravity, limited nutrients and repeated cleaning.

Independent analyses of station samples echo that picture. Reports on Bacteria Found On in the context of Astrobiology, Microbiology and Viro research describe organisms that have acquired changes likely to have helped those organisms survive repeated cycles of desiccation, radiation and chemical exposure. From my perspective, the “shocking new power” here is not cinematic virulence but a quiet, stubborn resilience that could complicate astronaut health while also revealing new molecular targets for drugs.

China’s Tiangong reveals microbes that do not exist on Earth

While the ISS shows how familiar microbes adapt, China’s Tiangong space station is starting to surface organisms that look genuinely new. Scientists on Tiangong have discovered a species of bacteria that does not exist on Earth, Named Niallia tiangongensis, which evolved from an Earth based ancestor inside China’s space station. The fact that a lineage can diverge so far, in such a short time and such a confined habitat, underscores how intense the selective pressures of orbit can be.

That discovery sits alongside another enigmatic resident of Tiangong, a strain simply dubbed The Unknown. Chinese scientists aboard the Tiangong Space Station identified The Unknown as a bacterium that does not match existing catalogs, raising the question of how we coexist with such organisms and whether it is just fascinating science or a potential risk, as highlighted in reports on The Unknown. I read these findings as a reminder that once we send life into orbit, we are not just storing it in a freezer; we are opening a new evolutionary branch that we will have to monitor and manage.

Viruses that evolved a new way to hunt superbugs

The most dramatic example of space granting microbes a new power comes from bacteriophages that were deliberately sent into orbit to see how they would change. In experiments involving T7 phages, the viruses responded to their low mixing environment by supercharging their ability to bind bacterial surface receptors, with specific genes continuing to evolve as they adapted to the constraints of microgravity, according to work on space evolved viruses. In practical terms, that means the phages learned to latch onto bacteria more efficiently when diffusion alone had to do the work of bringing virus and host together.

Analysis of the space station samples showed that, after an initial delay, the T7 phage successfully infected the E. coli, However the mutations it accumulated allowed it to attack strains that are normally resistant to T7, a shift documented in the Analysis of the coevolution experiment. Researchers then took the most successful space mutations and rebuilt them on Earth. The Raman Lab engineered phages with a variety of mutations that were successful in space to test their effectiveness against more complex bacterial communities, including the complexity of the human microbiome, as described in follow up work from The Raman Lab. In effect, space became a training ground for precision antimicrobials that can reach targets conventional phages cannot.

What makes these phages especially intriguing is how they changed at the molecular level. In orbit, the phages that won developed hydrophobic substitutions inside the Receptor Binding Protein they use to attach to bacteria, a structural tweak that improved their grip and emerged from evolutionary paths that would be hard to reproduce in a standard lab, according to analyses of But how mutations from space might solve an antibiotic crisis. From my vantage point, that is the “shocking new power” in its purest form: a virus that has literally retooled its binding machinery to go after bacteria that once ignored it.

From cleanrooms to clinics, the stakes are rising

These orbital experiments are unfolding against a backdrop of microbial resilience that starts long before launch. NASA Identifies 26 Resilient Bacterial Species Capable of Evading Cleanroom Sterilization, a set of organisms that can survive the harsh chemicals and protocols meant to keep spacecraft pristine, according to NASA. These hardy microbes complicate planetary protection and human exploration of Mars, because any contaminant that survives the cleanroom gauntlet is likely to be equally stubborn in transit and on other worlds.

Further reporting on these 26 previously unknown bacteria notes that they resist cleaning chemicals and cling to sterile surfaces by producing sticky films, a trait that could influence how we design future spacecraft and what the long term impact on space travel might be, as described in work on resilient microbes. When I connect that resilience with the adaptive leaps seen on the ISS and Tiangong, a clear message emerges. If we ignore how space reshapes microbial life, we risk seeding our missions with stowaways that are both harder to kill and more unpredictable. If we study and harness those changes, we might instead unlock a new generation of targeted therapies that were literally impossible to evolve on Earth.

More from Morning Overview