Researchers have unveiled a low cost metal catalyst that can tear apart plastic waste around ten times more efficiently than traditional platinum based systems, potentially slashing the cost of advanced recycling. By swapping scarce precious metals for earth abundant compounds, the work points toward industrial processes that turn stubborn plastics into valuable fuels and chemicals instead of landfill and microplastic pollution.

The breakthrough centers on a new way to drive hydrocracking and related reactions at relatively mild conditions, using a catalyst built from cheaper metals such as tungsten and nickel. If it scales, this approach could help close the loop on plastics that are currently burned, buried, or shipped overseas, and it could do so in a way that fits into existing petrochemical infrastructure rather than competing with it.

Why plastic is so hard to break, and why platinum has dominated

Modern plastics are engineered to survive heat, pressure, and sunlight, which is exactly what makes them so difficult to dismantle once they become waste. Long hydrocarbon chains in common materials like polyethylene and polypropylene resist attack, so conventional recycling often relies on melting and remolding, a process that downgrades quality and leaves mixed or contaminated streams effectively unrecyclable. Chemical routes that truly break polymers back into smaller molecules exist, but they typically demand high temperatures, high pressures, and expensive catalysts that are hard to justify for low value trash.

For years, platinum and other precious metals have been the workhorses of these reactions, especially in hydrocracking units that split heavy hydrocarbons into lighter fuels. Platinum is excellent at activating hydrogen and coordinating multiple reaction steps, but it is scarce and costly, and it can be poisoned by impurities that are common in post consumer plastics. Researchers working on a new generation of catalysts have explicitly targeted this bottleneck, noting that precious metals like platinum and palladium make it difficult to deploy advanced recycling at the scale of global plastic production.

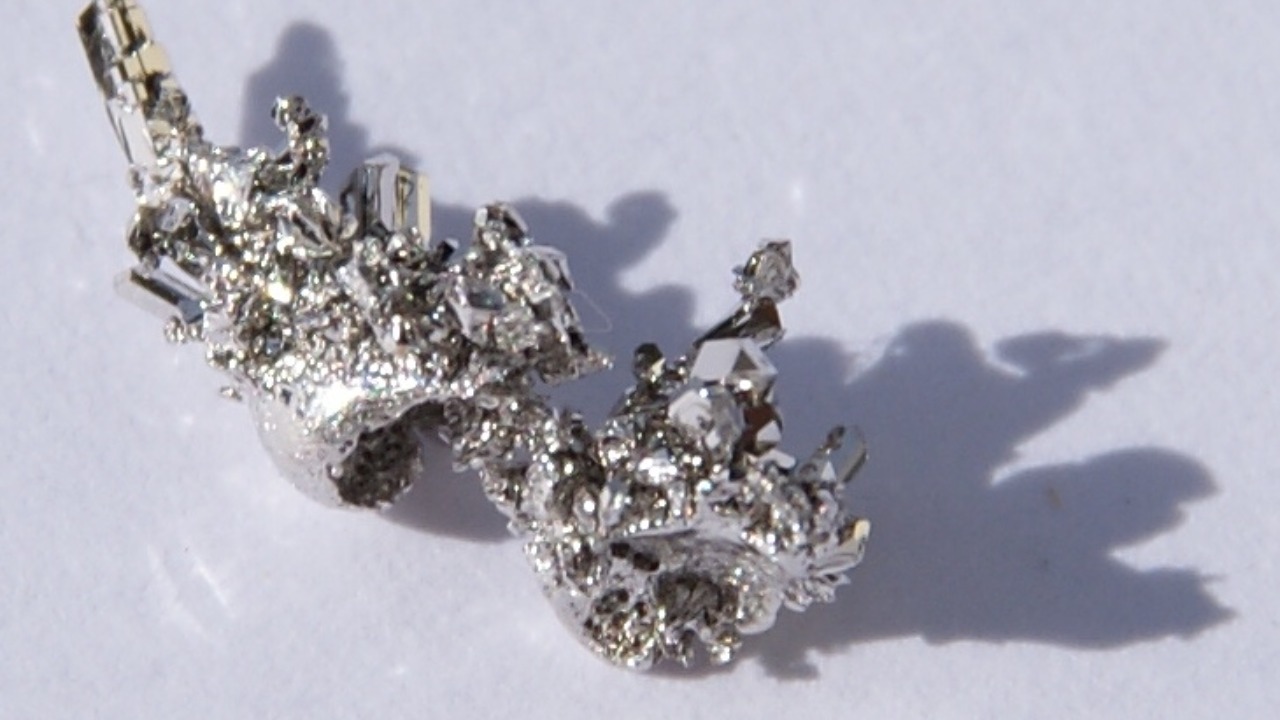

The tungsten carbide catalyst that outperforms platinum

The most striking advance comes from scientists who replaced platinum with tungsten carbide, a compound built from tungsten and carbon that is already produced in large volumes for cutting tools and wear resistant parts. In controlled tests, these researchers found that their tungsten carbide based system could convert plastic into useful products more than ten times as efficiently as comparable platinum catalysts, while operating under similar or even milder conditions. That performance jump is not just a laboratory curiosity, it directly attacks the cost and throughput limits that have kept chemical recycling on the margins.

In practical terms, the new catalyst accelerates the breakdown of polymer chains into shorter hydrocarbons that can be refined into fuels or used as feedstocks for fresh plastics, with a selectivity that reduces unwanted byproducts. The team emphasized that tungsten is far more abundant and less expensive than platinum, which opens the door to larger reactors and continuous processing lines that would be prohibitively costly with precious metals. One report on this work notes that scientists demonstrated that tungsten carbide can outperform platinum by more than tenfold in plastic upcycling, a result that directly supports the claim that a cheap metal catalyst can beat a traditional benchmark.

Hydrocracking, hydrogenolysis, and the rise of nickel and tungsten

To understand why these cheaper catalysts matter, it helps to look at the underlying chemistry. Hydrocracking, which has long been used in oil refineries, uses hydrogen and a catalyst to break heavy molecules into lighter ones, often in the diesel and jet fuel range. Applying hydrocracking to plastic waste has been challenging because polymers are more complex and contaminated than refinery streams, and because the catalysts must juggle multiple reactions without coking or deactivation. Researchers working on low cost systems have shown that carefully engineered surfaces can coordinate these steps, allowing hydrocracking to process plastic waste while relying on more abundant metals instead of platinum.

In parallel, other teams have turned to hydrogenolysis, a related process that uses hydrogen gas and a catalyst to cleave carbon carbon bonds directly. One group at Northwestern used a nickel based catalyst to cut through mixed plastic waste at relatively low temperatures, converting it into fuels and lubricants that can be reused instead of downcycled. Their work showed that a catalyst built around nickel could handle mixed streams that typically defeat mechanical recycling, and it did so in a way that points toward integration with existing hydrogen infrastructure in refineries and chemical plants.

From lab breakthrough to circular economy workhorse

The promise of tungsten carbide and nickel catalysts is not just faster reactions, it is compatibility with a circular economy model in which plastics are continuously reused rather than discarded. The tungsten carbide system, for example, was tested in conditions that mimic industrial reactors, with continuous feeds and outputs rather than batch experiments. Researchers reported that their scientists were able to design a process where materials are continuously reused, which is exactly the kind of setup needed to turn plastic waste into a steady input for chemical manufacturing rather than a sporadic clean up effort.

Public facing discussions of this work have highlighted how such catalysts could finally tackle plastics that are currently labeled unrecyclable, including multilayer packaging and mixed consumer waste. One widely shared explanation described how the future of plastic recycling is poised for a radical transformation thanks to new catalyst technology that can handle complex streams and turn them into valuable outputs. That account stressed that the breakthrough could enable recycling plastics previously deemed unrecyclable, a claim that aligns with the technical results reported for both tungsten carbide and nickel based systems.

Industrial stakes, policy pressure, and what comes next

The industrial stakes around these catalysts are significant because they intersect with both petrochemical economics and climate policy. Oil and gas companies already operate large hydrocracking and hydrogen units, so a catalyst that can drop into existing reactors and process plastic waste alongside conventional feedstocks could turn a liability into a revenue stream. At the same time, regulators in major markets are tightening rules on plastic waste exports and single use packaging, which increases pressure on producers to find credible recycling pathways that go beyond symbolic gestures.

From my perspective, the key question now is not whether tungsten carbide and nickel catalysts can outperform platinum in the lab, that has been convincingly demonstrated, but whether they can maintain activity and selectivity over months of continuous operation on dirty, real world waste. Scaling up will require pilot plants that test how these systems handle additives, dyes, and food residues, as well as business models that share value between waste collectors, recyclers, and chemical companies. Still, the fact that scientists have already shown a cheap metal catalyst beating platinum by more than a factor of ten in plastic upcycling, and that complementary work has proven low temperature conversion of mixed plastics into fuels, suggests that the technical foundation for a new generation of recycling plants is finally in place.

More from Morning Overview