In a significant stride towards addressing the global organ shortage, scientists have successfully converted a kidney from blood type A to universal type O and implanted it into a brain-dead recipient. This groundbreaking procedure, detailed in a study published in the American Journal of Transplantation, leverages a novel enzymatic method to remove blood type antigens from donor organs, potentially expanding the pool of viable transplants for recipients with different blood types.

Background on Blood Type Barriers in Kidney Transplants

ABO incompatibility presents a significant challenge in kidney donations. Kidneys from blood type A donors can trigger immune rejection in non-A recipients due to the presence of A antigens on the organ’s cell surfaces. This immune response is a major hurdle in organ transplantation, limiting the number of successful matches and contributing to the organ shortage crisis.

Universal type O kidneys are considered ideal donors as they lack A, B, or Rh antigens. This absence of antigens makes them compatible with all blood types, significantly reducing the risk of organ rejection. However, the current limitations in transplant matching mean that only about 40% of potential donors are compatible with recipients, leading to long waitlists and thousands of deaths annually.

Historically, the ABO blood group system has been a significant determinant in organ transplantation. The system, discovered in the early 20th century, categorizes blood into four types: A, B, AB, and O. Each type has specific antigens that, when introduced into a body of a different blood type, can trigger a severe immune response. This response, known as an immune rejection, can lead to organ failure and potentially death, making blood type compatibility a crucial factor in successful organ transplants.

Moreover, the distribution of blood types varies globally, with type O being the most common and type AB the least. This uneven distribution further exacerbates the organ shortage crisis, as the demand for type O organs, which can be donated to any recipient, far outstrips the supply. The development of a method to convert organs to type O could therefore have profound implications for organ transplantation, potentially saving countless lives worldwide.

The Enzymatic Conversion Process

The groundbreaking procedure involves the use of specialized enzymes to strip A antigens from the surface of a blood type A kidney, effectively transforming it into a type O organ ex vivo prior to implantation. This enzymatic conversion process is a significant advancement in the field of organ transplantation, potentially increasing the number of viable organs for transplantation.

The kidney undergoes a lab-based perfusion technique, which involves circulating a solution through the organ to facilitate antigen removal without damaging its viability. Following the conversion process, the kidney is tested for functionality and the absence of residual antigens before proceeding to implantation.

The enzymatic conversion process is based on decades of research into the nature of blood type antigens and how they interact with the immune system. The enzymes used in the process are derived from specific bacteria that have evolved to feed on the sugars that form the A and B antigens. By applying these enzymes to the organ, scientists can effectively ‘eat away’ the antigens, converting the organ to type O. This process represents a remarkable application of evolutionary biology to address a pressing medical challenge.

However, the process is not without its complexities. The enzymes must be carefully controlled to ensure they remove all the antigens without damaging the organ itself. This requires a delicate balance and precise monitoring, demonstrating the intricate nature of the procedure. Despite these challenges, the successful conversion of a kidney in this study represents a promising step forward in the field.

The Implantation Procedure

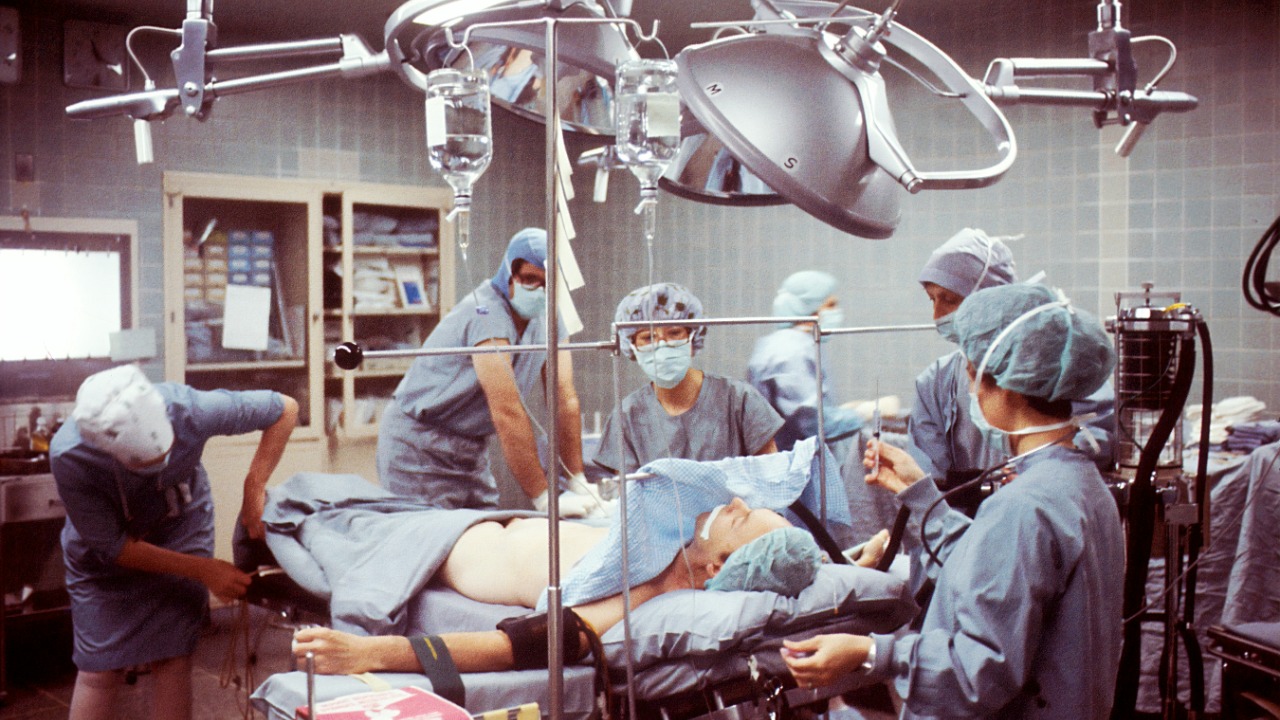

The converted type O kidney was surgically implanted into a brain-dead recipient, serving as a model to evaluate short-term organ function without the ethical concerns associated with live transplantation. This approach allowed the research team to monitor the organ’s performance in a controlled environment, ensuring the procedure’s safety.

Post-implantation, the kidney showed signs of immediate function, including urine production and stable vascular integration, indicating a successful conversion and implantation process. The choice of a brain-dead recipient serves as a bridge to future human trials, ensuring the procedure’s safety in a controlled environment.

The implantation procedure is a critical stage in the transplantation process. It involves surgically connecting the donor organ to the recipient’s blood vessels and urinary system. This is a complex procedure that requires a high degree of surgical skill and precision. The success of the procedure is not only dependent on the compatibility of the organ but also on the surgical team’s ability to ensure the organ is correctly positioned and functioning within the recipient’s body.

In this study, the use of a brain-dead recipient allowed the research team to focus solely on the technical aspects of the procedure, without the added complexities of managing a living patient. This approach provided valuable insights into the procedure’s feasibility and safety, laying the groundwork for future trials with living recipients.

Research Team and Study Publication

The experiment was conducted by a team of researchers from the University of Toronto and collaborators, who are engaged in ongoing work in xenotransplantation and organ modification. The study, published in the American Journal of Transplantation, provides peer-reviewed validation of the conversion and implantation outcomes, marking a significant milestone in the field.

The development of this antigen-modification technology was supported by funding from Canadian health agencies, highlighting the potential of this approach for broader clinical use in organ transplantation.

The research team behind this groundbreaking study is composed of experts in the fields of transplantation, immunology, and bioengineering. Their diverse backgrounds and combined expertise were instrumental in developing and executing the complex enzymatic conversion process and implantation procedure. The team’s multidisciplinary approach underscores the importance of collaboration in advancing medical science.

The study’s publication in the American Journal of Transplantation is a testament to the rigorous scientific scrutiny the research underwent. Peer-reviewed journals such as this one are the gold standard in scientific research, ensuring that the studies they publish are of high quality and contribute significantly to their respective fields. The publication of this study in such a prestigious journal underscores its potential impact on the field of organ transplantation.

Implications for Future Organ Transplants

This conversion method could potentially increase the usable donor pool by making incompatible kidneys viable for transplantation. This could significantly reduce wait times for over 100,000 patients on U.S. transplant lists alone, addressing the critical issue of organ shortage.

The enzymatic conversion process could also be adapted for other organs such as livers or hearts, achieving universal compatibility and further expanding the pool of viable organs for transplantation. However, there are ethical and regulatory hurdles to overcome, including the need for FDA approval before live human trials can commence.

The potential implications of this study for the future of organ transplantation are vast. By increasing the pool of compatible organs, the enzymatic conversion process could dramatically reduce the number of patients waiting for a transplant, thereby decreasing mortality rates associated with organ failure. Furthermore, the process could also reduce the need for immunosuppressive drugs, which are currently used to prevent organ rejection but can have serious side effects.

Moreover, the successful conversion of a kidney could pave the way for the conversion of other organs. This could revolutionize the field of organ transplantation, making it possible for patients of any blood type to receive a transplant from any donor. However, it is important to note that this is still a nascent field of research, and much work remains to be done before these possibilities can become a reality.

Challenges and Next Steps

While the study marks a significant advancement, there are potential risks to consider. Incomplete antigen removal could lead to hyperacute rejection, a risk that was mitigated in this study through rigorous testing. As the research progresses, these risks will need to be carefully managed to ensure the safety and effectiveness of the procedure.

Future advancements include scaling the process for multiple organs and conducting long-term function studies in animal models. The researchers aim to apply the procedure in human trials within the next 5–10 years, pending further validation. This timeline reflects the careful and meticulous approach required in medical research, ensuring that the procedure is safe and effective before it can be applied in clinical settings.