Bipolar disorder can feel like a storm that erupts from nowhere, yet for decades the brain circuitry driving those brutal mood swings has remained frustratingly vague. Now, converging lines of evidence are zeroing in on a small, deep structure that appears to sit near the heart of the illness, reshaping how I think about both its biology and its treatment.

Instead of a diffuse, everywhere-and-nowhere problem, researchers are mapping a specific hub whose misfiring neurons may help trigger the extreme highs and crushing lows that define the condition. That shift, from broad association to pinpointed circuitry, is already inspiring new ideas for therapies that go beyond symptom control and aim at the roots of bipolar pathology.

The overlooked hub: paraventricular thalamic nucleus under the spotlight

For years, the thalamus has been treated as a kind of relay station in psychiatric research, important but rarely the star of the show. That is changing as scientists home in on the paraventricular thalamic nucleus, or PVT, a sliver of tissue buried deep in the brain that now looks like a causative region in bipolar disorder. In new work from a Japanese team, the PVT was identified as a key site where specific neurons appear to drive pathological mood states, with the study explicitly highlighting the paraventricular thalamic nucleus as both a causative region and a therapeutic target. By tracing how this nucleus connects to emotion and reward circuits, the researchers argue that its dysfunction can help explain why mood shifts in bipolar disorder are so abrupt and so hard to regulate.

What makes this finding more than an anatomical curiosity is the way it links microscopic cell behavior to lived experience. The same work suggests that focusing on these neurons as a therapeutic target might help restore the regulation of calcium and ion channel functions, mechanisms that are central to how brain cells fire and communicate. In other words, the PVT is not just a passive relay, it is a control node whose misregulated channels can destabilize entire networks. A companion report on the same project underscores that this focusing on PVT neurons could directly influence how mood circuits reset after stress, which is exactly where many people with bipolar disorder struggle.

From tissue to circuits: how scientists tied the PVT to bipolar pathology

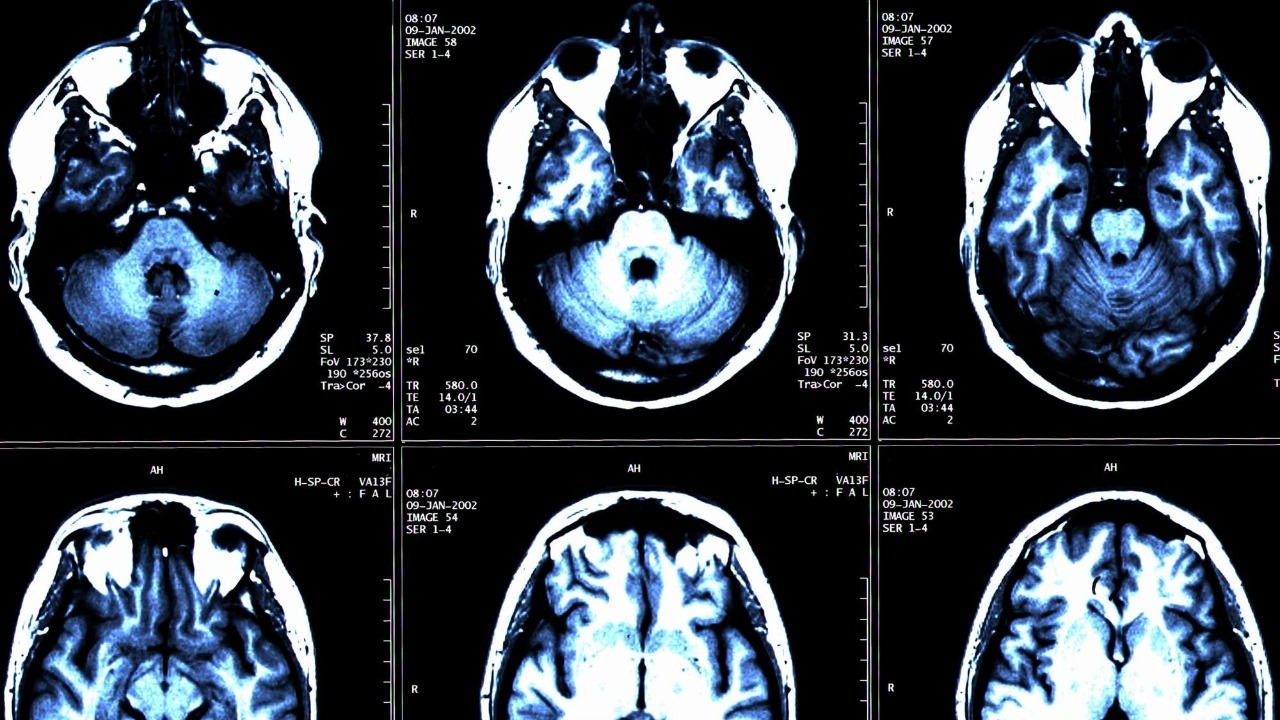

Pinpointing a structure is one thing, proving that it matters in real human brains is another. That is where recent analysis of human brain tissue becomes crucial, suggesting that a small and often overlooked region deep within the brain may play a central role in bipolar pathology. Researchers examined postmortem samples and found molecular signatures that implicate this region in the illness, an approach that moves beyond imaging correlations to cellular-level evidence. The work is summarized as a recent analysis that aligns strikingly with the PVT findings, reinforcing the idea that this deep structure is not a bystander but a driver of disease processes.

What stands out to me is how directly these tissue findings feed into treatment thinking. The same line of research emphasizes that therapies that aim to protect these neurons or restore their function might offer relief where current treatments fail, especially for patients whose symptoms remain severe despite standard mood stabilizers. The authors describe how Therapies that shield vulnerable PVT neurons, or repair their signaling, could change the trajectory of the illness rather than just dampening episodes. They also point to Advanced imaging and molecular tools that can track these neurons in living patients, opening the door to circuit-specific drugs or neuromodulation strategies that are far more precise than today’s medications.

Extreme moods mapped: pleasure, pain and the visual brain

While the PVT work drills into a tiny nucleus, other teams are zooming out to see how whole networks behave during mood swings. Earlier work highlighted how Researchers used brain scans to uncover areas responsible for mood swings and pleasure response in bipolar disorder, identifying regions that light up differently when people anticipate or experience rewards. That study, shared by Researchers focused on how the brain’s reward circuitry misfires, helps explain why mania can feel intoxicatingly pleasurable even as it wrecks sleep, finances and relationships. It also hints at why depressive phases can flatten any sense of enjoyment, as if the reward system has been switched off.

Another line of evidence comes from work that tracked brain activity Across all participants with and without bipolar disorder, revealing heightened activity in an area involved in the experience and anticipation of pleasure. The scientists reported that this signal was especially pronounced for participants with bipolar disorder, suggesting a kind of hypersensitivity in circuits that evaluate emotional salience. The initial report framed this as a finding that Across diagnostic groups, the same region was active, but it was dialed up for bipolar participants, which fits with the lived reality of emotions that feel too bright, too sharp and too hard to turn down.

State-related changes: what the visual system reveals about mood

One of the more surprising developments, at least to me, is how the visual system is emerging as a window into bipolar states. A study led by Ron Goldberg reports Increased Specialization in Visual Regions Indicates State-Related Alterations in Bipolar Disorder, showing that the way visual areas process information shifts depending on whether someone is in a manic, depressive or euthymic phase. The authors describe how this Increased Specialization in visual regions may serve as a marker of current mood state, hinting at future tools that could read out brain state more objectively than symptom checklists alone.

The same report, which centers on Visual Regions Indicates State and Related Alterations in Bipolar Disorder, underscores that these changes are not static traits but dynamic shifts that track with symptoms. That nuance matters for both diagnosis and treatment, because it suggests that the brain’s sensory systems are actively reshaped by mood episodes rather than simply reflecting a fixed vulnerability. In practical terms, it means that a scan of visual cortex activity could one day help clinicians distinguish between a mixed state and a full manic episode, or between bipolar depression and unipolar depression. The work by Ron Goldberg and colleagues adds an unexpected sensory dimension to a disorder usually framed in purely emotional terms.

Circuits, metabolism and the next generation of treatments

All of these findings sit within a broader effort to decode how entire neural circuits go awry in bipolar disorder. A comprehensive review titled Introduction, Bipolar describes the condition as one of the most intricate and multifaceted psychiatric illnesses, affecting millions worldwide and involving widespread dysregulation across mood, cognitive and reward networks. The authors argue that understanding bipolar disorder requires mapping how these networks interact, not just cataloging isolated regions, and they highlight Introduction of circuit-based models as a path toward more targeted therapies. A related link to Bipolar research emphasizes that mood episodes emerge from dysregulated loops connecting thalamus, cortex and limbic structures, which fits neatly with the new focus on the PVT as a central hub.

At the same time, another body of work is pushing beyond circuits to the cellular energy systems that keep those circuits running. Over the past decade evidence from multiple research trajectories have converged to provide compelling evidence that impaired glucose metabolism, insulin resistance and mitochondrial dysfunction are not side notes but core issues laying at the root of BD. One paper, framed around how Over the years metabolic findings have accumulated, focuses on the PI3K/AKT/HIF1-a pathway and the potential of ketogenic diets to stabilize mood by improving mitochondrial function. This metabolic angle dovetails with the PVT story, since neurons in that nucleus are highly energy dependent and may be especially vulnerable when insulin signaling is off-kilter.

More from Morning Overview