For decades, aging has looked like an unavoidable slide into frailty, driven in part by an immune system that slowly loses its edge. Now a wave of experiments in mice and human cells suggests that decline may be at least partly reversible, with researchers learning to reprogram, prune, and even transplant key immune components to restore youthful function. The work is still early, but it points to a provocative possibility: by tuning the immune system, scientists may be starting to slow aging at its biological roots.

Instead of chasing a single “longevity pill,” researchers are dissecting how immune cells are born, trained, and exhausted over a lifetime, then testing ways to reset those processes. I see a pattern emerging across multiple labs and approaches, from genetic tweaks in bone marrow to mRNA therapies that reawaken dormant tissues, all converging on the same idea that the immune system is both a driver of aging and a powerful lever to push it back.

Why an aging immune system drags the rest of the body down

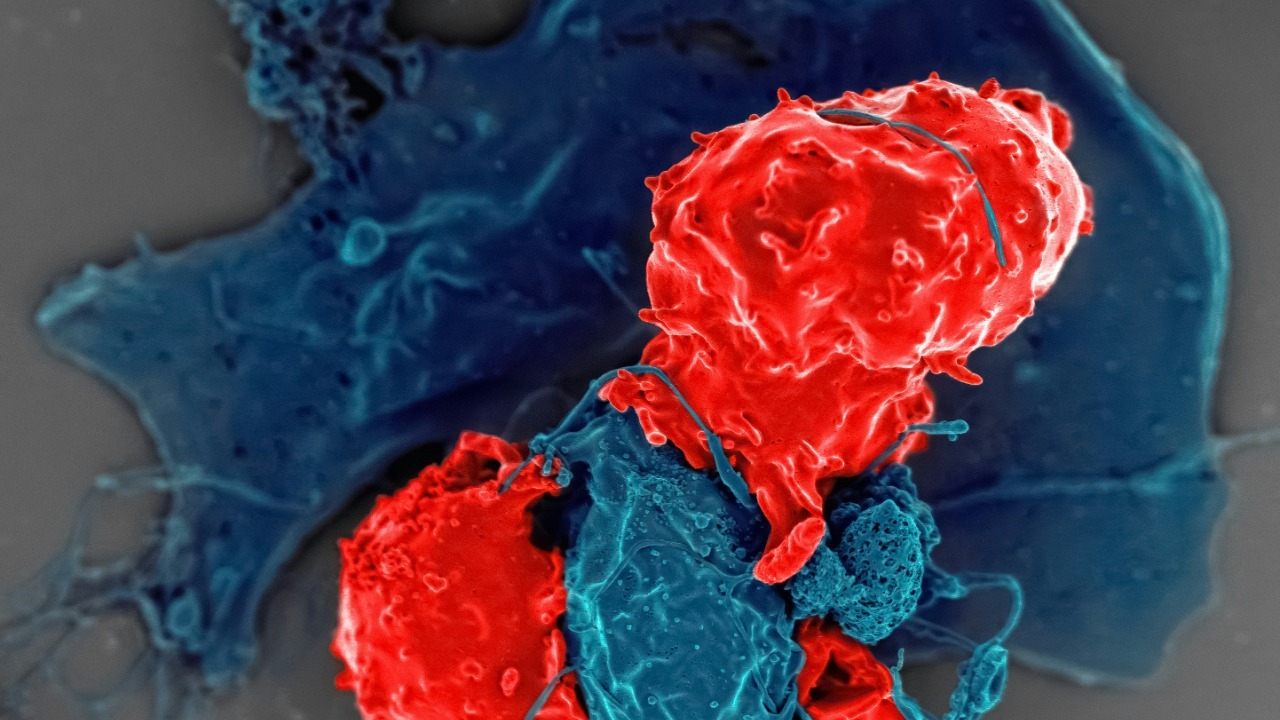

Immune aging is not just about catching more colds, it reshapes the entire landscape of disease risk. As people grow older, their defenses against new infections weaken, while simmering inflammation and misfiring cells fuel conditions like cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, and cancer. Researchers at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases have detailed how Aging is associated with a reduced ability to generate immune responses against novel infections, a pattern that was starkly illustrated during the Covid‑19 pandemic when older adults faced far higher mortality.

At the same time, the aging immune system does not simply go quiet, it often becomes chronically activated in the wrong ways. A Novel study from New York showed how an aging immune system can actively fuel cancer growth, helping tumors evade surveillance and thrive in older tissues. When I connect these dots, the logic of targeting immunity to slow aging becomes clear: if immune decline is upstream of so many age‑related diseases, then rejuvenating those cells could ripple outward to protect multiple organs at once.

Reprogramming the body’s T‑cell factories

One of the most striking advances comes from efforts to restore the body’s supply of T cells, the white blood cells that coordinate immune attacks and remember past threats. In youth, T cells mature in the thymus, a small organ in the chest that shrinks dramatically with age, leaving older adults with a dwindling pool of fresh defenders. Researchers at MIT and the Broad Institute have shown that MIT and Broad Institute scientists can temporarily program cells in the liver to mimic some of the thymus’s functions, effectively creating an auxiliary training ground for new T cells.

In that work, the team found that Stimulating the liver to produce signals normally made by the thymus could reverse age‑related declines in T‑cell populations and improve responses to cancer immunotherapy in older animals. A related report from MIT highlighted how new study data suggest this strategy might help older patients respond better to vaccines and checkpoint inhibitors, two areas where age has historically blunted benefits. I see these liver‑based thymus mimics as a kind of software update for the immune system, rewriting instructions in existing tissues rather than trying to regrow a vanished organ.

mRNA and molecular “tuning” of aging defenses

Another front in this quiet revolution uses the same mRNA technology that powered Covid‑19 vaccines, but now aimed at dialing immune aging backward. As the immune system weakens with age, scientists have identified a protein called ReHMGB1 that appears to play a surprising role in supporting T‑cell survival. In work highlighted by a Dec report, As the immune system weakens, delivering mRNA that encodes ReHMGB1 can restore some of its lost strength in animal models, boosting the survival of key T cells that would otherwise fade.

Social media coverage of this research underscored how Scientists from MIT have found a way to boost aging immune systems with a new mRNA therapy that targets ReHMGB1, reframing mRNA as a tool for immune maintenance rather than just emergency vaccination. A separate analysis of the same line of work noted that Research from MIT, Broad, and collaborators could make cancer immunotherapy treatments work better in older individuals by restoring the molecular environment that young T cells rely on. To me, these mRNA approaches look like precision knobs on the immune system’s control panel, letting scientists tune specific proteins up or down without permanently rewriting DNA.

Pruning and transplanting to rebuild youthful immunity

Not all rejuvenation strategies involve adding new signals, some work by carefully taking things away. At the National Institutes of Health, Researchers found that depleting certain hematopoietic stem cells in aged mice improved their immune systems, essentially clearing out dysfunctional progenitors so healthier ones could repopulate the blood. A companion report from the same program described how Mar findings on stem cell changes in aged mice are being used to design follow‑up studies that might one day help protect older people against infections.

Other teams are going further, swapping out entire immune compartments between young and old animals. In work from Stanford Medicine and, scientists showed that transplanting bone marrow from young mice into older ones could revitalize immune responses and even improve the function of distant organs. A more detailed account of the same project noted that Now a study conducted in mice by Stanford Medicine and the National Institute of Health, Rocky Mountain Laboratories provides tangible evidence that resetting the immune system can have body‑wide benefits. When I look at these transplant and depletion experiments together, they suggest that aging immunity is not fixed, it can be rebuilt if scientists are willing to re‑engineer the underlying cell populations.

The discovery of “pro‑youth” immune cells

Alongside these engineering feats, researchers are uncovering entirely new types of immune cells that seem wired to keep tissues young. A team described A newly recognized set of immune cells that track a person’s stage of life and respond differently as aging progresses, hinting at built‑in programs that could be harnessed to slow decline. Neuroscientists have also reported that scientists uncover immune cells in the brain that may hold the secret to slowing aging, by clearing senescent cells and toxic debris that accumulate over time.

In parallel, another group reported that Scientists Have Discovered a Special Type of Immune Cell That Slows Aging, describing how these cells patrol tissues and help maintain a youthful environment. A separate summary of the same work emphasized that this Immune Response to Senescent Cells could be tuned to enhance the clearance of damaged cells without triggering chronic inflammation. I see these discoveries as the immune system’s equivalent of finding longevity‑promoting neurons in the brain, specialized cell types that might be amplified or transplanted to extend healthy function.

More from Morning Overview