The idea of turning back the clock on the immune system has moved from science fiction to a concrete experimental strategy. A cluster of new studies suggests it may be possible to restore some of the vigor of youthful immunity by re‑creating key signals that fade with age and redirecting them to new tissues.

Instead of trying to rebuild every aging organ, researchers are learning to mimic the body’s own developmental cues, from thymus hormones to microbial metabolites, to coax older immune cells into acting young again. The work is still early, but it points to a future in which immune decline is treated as a reversible condition rather than an inevitable slide.

Why the aging immune system falters

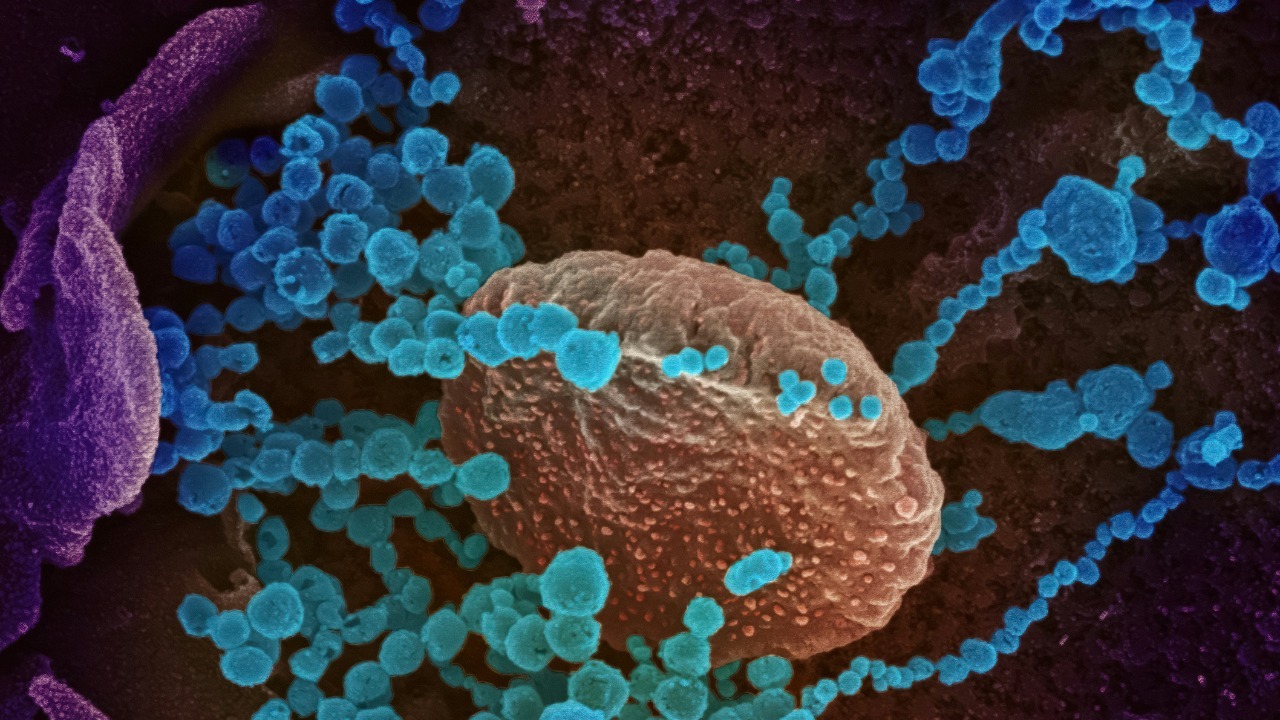

Immune aging starts with a slow but relentless weakening of core defenses. As people grow older, immune function gradually weakens, T‑cell numbers decline, and their ability to respond rapidly to new threats falls off, a pattern that Scientists have now mapped in detail. The thymus, the small organ in the chest that trains T cells, is central to this story, since its activity shrinks steadily across adulthood.

By around age 75, its activity is greatly reduced, leading to fewer newly generated T cells and a growing reliance on older, exhausted cells that have already seen years of infections and vaccines. As the immune system weakens, older adults become more vulnerable to respiratory viruses, shingles, and cancers that a younger immune system might have contained, a trend that has driven scientists to search for ways to restore the signals that support T‑cell survival.

The MIT blueprint: mimicking thymus signals outside the thymus

In Dec, Scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, or MIT, reported a striking way to bypass the failing thymus by recreating its chemical instructions elsewhere in the body. According to their work, Scientists at the identified key thymic factors that normally guide immature T cells and then designed a system to mimic thymic factor secretion in other tissues.

The MIT team focused on the idea that you do not necessarily need a fully regrown thymus if you can reproduce the molecular environment that supports T‑cell development. Their approach uses targeted delivery so that other organs can temporarily act as a stand‑in for the shrinking thymus, effectively creating a distributed training ground for new T cells that can respond to infections and vaccines with more youthful vigor, a strategy that aims bypass the shrinking without permanent genetic changes.

mRNA as a temporary immune reset button

The same group and their collaborators have pushed this concept further by using the same kind of mRNA technology that underpins COVID‑19 vaccines. Using mRNA to deliver three key factors that usually promote T‑cell survival, the researchers were able to rejuvenate the immune system in animal models by briefly turning other tissues into thymus‑like factories, an approach described as Using mRNA to re‑create developmental signals on demand. The factors were chosen because they are central to T‑cell survival and development, and because they can be switched off as the mRNA degrades.

Stimulating the liver to produce some of the signals of the thymus can reverse age‑related declines in T‑cell populations and enhance responses to vaccines and even cancer immunotherapies, according to work that describes Stimulating the liver as a temporary immune organ. Importantly, the T cell production boost generated through the liver was temporary, which reduces the risk of overstimulating the immune system and triggering autoimmune problems, a safety feature highlighted in a report noting that this transient surge in T cells Importantly fades as the mRNA signal disappears.

From lab concept to clinical strategy

Researchers are already sketching how these ideas might translate into human therapies. One ongoing effort, The TRIIM‑X trial, is an expanded pilot clinical study that will evaluate a personalized combination treatment regimen for thymus regeneration and immune rejuvenation, building on earlier work that suggested certain hormone and drug cocktails could regrow thymic tissue, as described in The TRIIM protocol. While TRIIM‑X does not use mRNA, it reflects the same conviction that the thymus is not a lost cause in older adults.

Other researchers are investigating whether transplanted stem cells could help regrow functional thymus tissue, exploring cell‑based ways to rebuild the organ that supports T cell survival, a direction highlighted in reports that note how The MIT team complements these regenerative strategies. Together, these approaches suggest a future menu of options, from drugs and mRNA pulses to cell transplants, that could be tailored to a person’s age, infection history, and cancer risk.

Rejuvenation beyond the thymus: gut microbes and systemic aging

The immune system does not age in isolation, and some of the most intriguing rejuvenation data come from the gut. In research published in Jan in Stem Cell Reports, a team from Cincinnati Children and Ulm University in German showed that replacing the microbiota in aging intestines with microbes from younger donors could make aging intestines young again, a finding that underscores The power of young bacteria to reset tissue function. Since gut microbes constantly train immune cells, especially in the intestinal lining, this kind of intervention could indirectly refresh immune responses far from the gut itself.

These systemic effects are part of why some scientists now talk about a temporary immune‑support system rather than a single organ fix. Reports describing a 4th Edition 2026 of a longevity‑focused analysis note that Edition researchers see value in orchestrating multiple levers, from thymus signals to microbiota, to create a coordinated, time‑limited boost. In that view, the goal is not permanent hyper‑immunity but a controlled window in which older bodies can respond to vaccines, clear infections, or tackle cancers with something closer to midlife strength.

More from Morning Overview