Deep in the Atlantic Ocean, far from any coastline and out of reach of sunlight, scientists have mapped a sprawling undersea landscape that looks uncannily like a ghostly metropolis. Towering spires, clustered plazas and crumbling walls of pale rock rise from the seafloor, forming what researchers now call the Lost City hydrothermal field, a natural complex unlike anything else on Earth. What makes this “city” extraordinary is not only its architecture of stone chimneys but the alien chemistry and resilient life that thrive there, hinting at how life itself may have begun.

The site sits more than 2,300 feet beneath the surface, hidden in the dark Atlantic and powered not by volcanic fire but by reactions deep within the planet’s mantle. In this otherworldly environment, vents rich in hydrogen and methane feed dense microbial communities that live without sunlight, relying instead on chemical energy. As I look at the emerging science around this place, it is hard to escape the sense that the Lost City is both a window into Earth’s distant past and a warning about how easily we could damage a system that took millions of years to build.

Where the “city” really is and how it was found

The Lost City sits on a mountain along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a region where the seafloor is slowly pulling apart and exposing deep rock. Explorers first stumbled on this strange landscape in 2000 while surveying a massif now known as the Atlantis structure, finding a cluster of pale towers that looked more like ruined skyscrapers than typical volcanic vents. Later mapping showed that the field lies about 2,300 feet below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean, in a region of slow seafloor spreading where mantle rocks are unusually close to the water.

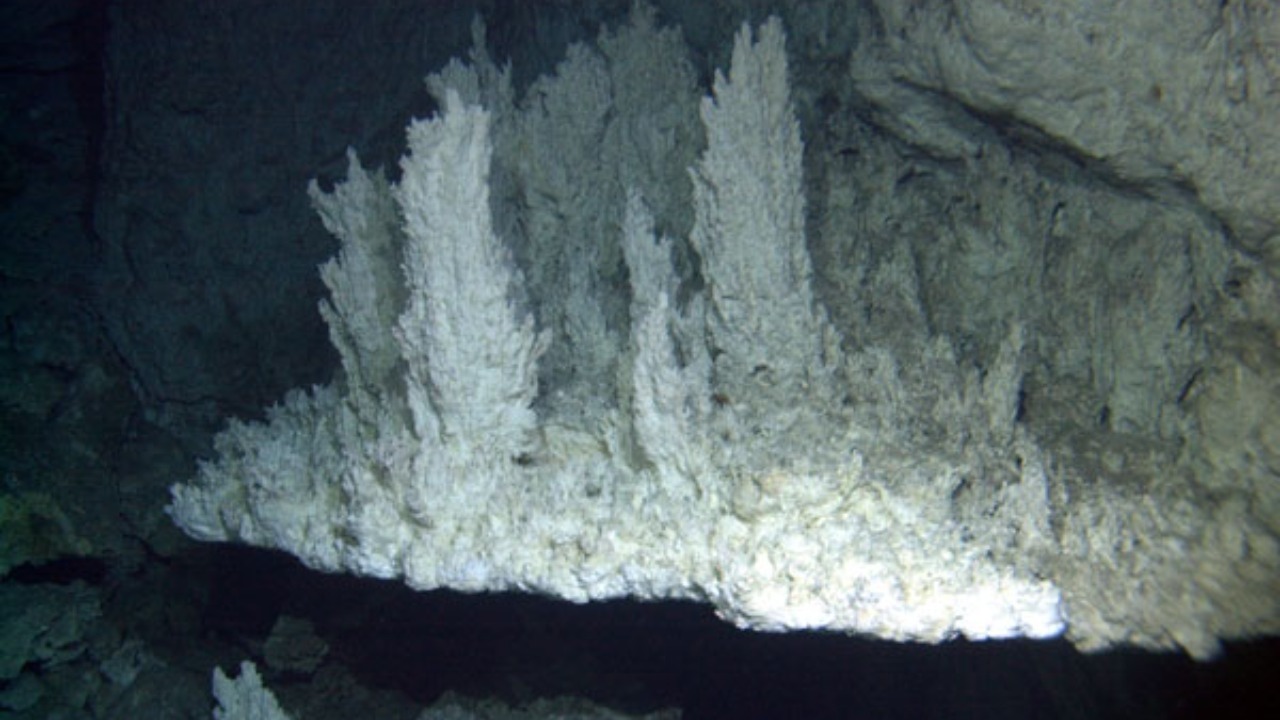

Subsequent expeditions revealed that the formation first spotted was only one part of a much larger complex. Researchers documented more than 30 individual structures spread across the seafloor, some rising tens of meters high and forming what looks like an undersea neighborhood of towers and buttresses. The vents are built almost entirely from carbonate minerals that precipitate out of alkaline fluids, creating dazzling white and cream colored chimneys that early reports described as a cluster of dazzling white towers on the flanks of the Atlantis massif.

A skyline of stone: towers, plazas and carbonate walls

What sets the Lost City apart visually is its architecture. Instead of the dark, smoke-belching chimneys familiar from volcanic “black smoker” vents, this field is dominated by pale carbonate towers that can reach up to 60 meters in height, forming a skyline of jagged spires and terraces. These structures are built from nearly 100 percent carbonate, the same basic material as limestone caves, and range in color from clean white to cream and darker gray as they age and react with seawater. One early expedition leader, Kelley, remarked that “Rarely does something like this come along that drives home how much we still have to learn about our own planet,” a reaction that captured the shock of seeing such an extensive carbonate city on the seafloor for the first time.

At the base of the tallest edifices, the chimneys merge into buttresses and walls that enclose small basins, giving the impression of plazas and courtyards carved in stone. The Lost City is made up of impressive carbonate rock towers, some reaching exactly 60 meters, and the vents that feed them are nearly 100 percent carbonate, a composition that makes them mechanically strong yet chemically reactive. As fluids seep and gush through these chimneys, they continually add new layers of mineral, so the “buildings” are still under construction even as they slowly crumble at the edges.

The alien chemistry powering this undersea world

Unlike volcanic vent fields that are driven by magma, the Lost City is powered by a process called Serpentinization, in which seawater percolates into mantle rocks rich in olivine and pyroxene and triggers exothermic reactions. These reactions warm the surrounding waters and generate hydrogen rich fluids with a pH over 9, which then mix with the colder, more acidic ocean outside and cause calcium carbonate to precipitate. The result is a network of alkaline springs that build towering chimneys while releasing hydrogen and methane in quantities large enough to sustain entire ecosystems. Scientists studying the site describe it as a unique off axis hydrothermal system where relatively low temperature fluids still manage to create huge carbonate chimneys, a pattern summarized in Abstract Lost City.

The chemistry here has implications far beyond geology. Biochemists who study the origin of life argue that alkaline hydrothermal vents like these were essential to early biochemical evolution, because their porous minerals and steep pH gradients can drive energy rich reactions. In this view, the labyrinth of microscopic pores inside Lost City chimneys could have acted as natural reactors, concentrating organic molecules and helping to convert simple gases into the building blocks of life. One researcher has emphasized that Alkaline hydrothermal vents, where high pH fluids flow into more acidic ocean water, provide exactly the kind of natural battery that early cells would have needed. That makes the Lost City not just a curiosity but a working model of conditions that may have existed billions of years ago.

Life in the dark: microbes, methane and a possible template for other worlds

Despite the lack of sunlight, the Lost City is far from lifeless. Microbes found in the chimneys at Lost City, named for the research vessel Atlantis that first explored the area, appear to live off large amounts of methane and hydrogen that seep from the vents. These organisms rely on chemosynthesis rather than photosynthesis, using chemical gradients as their energy source in a way that is fundamentally different from surface ecosystems. Early surveys reported that Microbes in this field tap into hydrogen and methane as their primary fuels, highlighting how robust life can be when given access to the right chemistry.

More detailed biological work has shown that the carbonate surfaces and fluid seawater interfaces at the site host a surprising diversity of eukaryotic organisms as well. Studies of the field describe a community that includes protists and other small eukaryotes living alongside bacteria and archaea, all adapted to the high pH and unusual chemistry of the vents. The fact that such a complex ecosystem can thrive nearly 2,300 feet down, Hidden from sunlight, strengthens the case that similar chemistry driven life could exist on icy moons like Europa or Enceladus. If microbes can build a food web here using only hydrogen fueled chemosynthesis, as later comparisons with other vent systems suggest, then the basic ingredients for life may be more common in the universe than surface based biology implies.

Why scientists say it is “unlike anything seen before”

Researchers who have worked at the Lost City repeatedly stress that it does not fit neatly into existing categories of hydrothermal systems. Typical black smokers are hot, acidic and short lived, while this field is cooler, highly alkaline and appears to have been active for hundreds of thousands of years. Reports describe the Lost City as Deep Beneath The Ocean Is Unlike Anything Seen Before on Earth, emphasizing that its combination of tall carbonate towers, hydrogen rich fluids and long lived activity has no known counterpart. The site has been characterized as Lost City Deep Beneath The Ocean Is Unlike Anything Seen Before on Earth, a phrase that captures both its physical scale and its scientific novelty.

More from Morning Overview