When researchers finally cracked open the canisters from asteroid Bennu, they were not just sifting through dust. They were staring at a chemical time capsule packed with sugars, amino acids, salt water traces and even ancient “stardust” grains that predate the Sun. The wild surprise is how complete this extraterrestrial pantry looks, with ingredients that map directly onto the chemistry of life on Earth.

What began as a mission to sample a near-Earth asteroid has turned into a sharp new test of the idea that impacts helped seed our planet with the raw materials for biology. I see the Bennu haul forcing scientists to rethink how common those ingredients might be across the Solar System, and how early they were mixed into the rocks that later rained down on Earth.

The day Bennu’s box was opened

The moment the sample container was first opened, the scene was closer to a forensic lab than a sci-fi movie, with curators and chemists watching for the slightest hint of contamination. Co-lead author Tim McCoy, curator of meteorites at the National Museum, has described seeing the grains as they were first exposed, a reminder that this material had never before touched Earth’s air. That pristine status is what makes the chemistry so compelling, because every molecule can be traced back to processes on Bennu or its long-lost parent world. Early lab work quickly confirmed that the samples really were from asteroid Bennu, matching the dark, carbon rich material the spacecraft had seen up close.

The mission that delivered those grains, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx, was designed to bring back untouched rock from a primitive body and return it to Earth for detailed analysis. In video briefings, scientists have emphasized how “pristine” is not just a buzzword but a technical requirement, because even trace contamination could blur the signal of fragile organics. Another presentation on the Bennu haul underscored that these are “no ordinary rocks,” with researchers explaining how the sample hardware was engineered so NASA could preserve volatile compounds that would normally be lost in meteorites that burn through the atmosphere.

A salty, ocean-world origin story

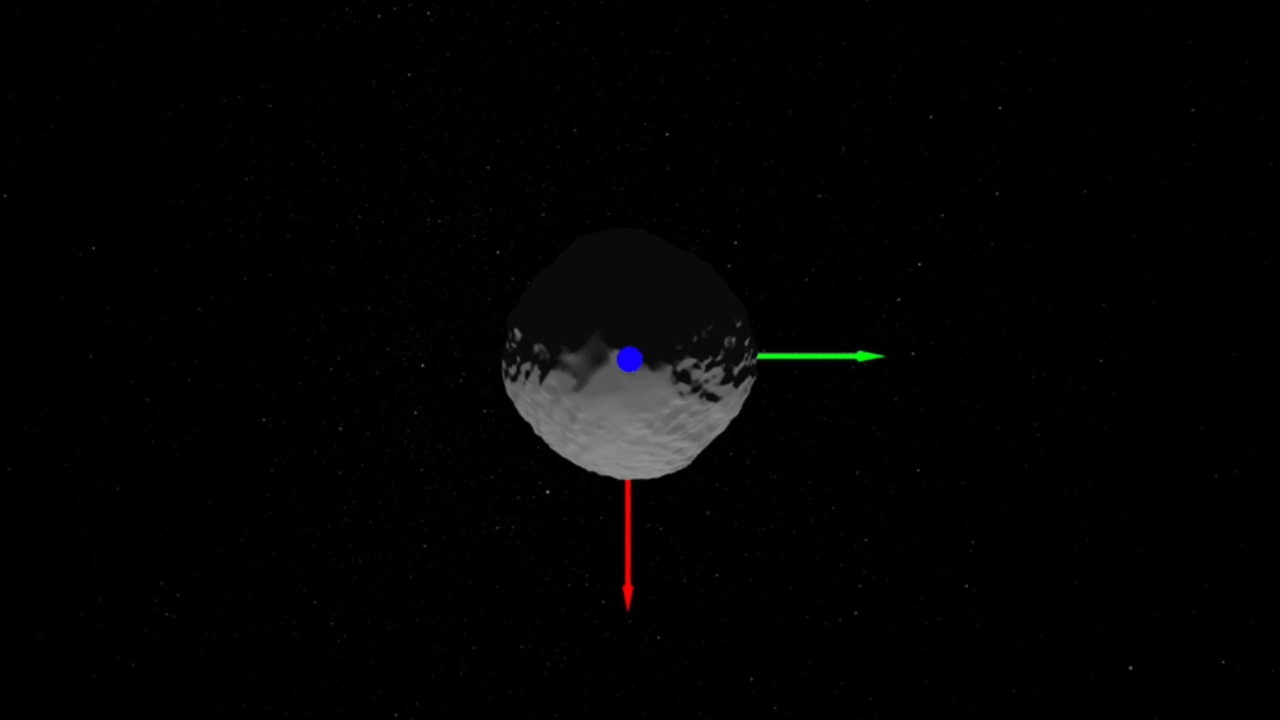

Once the first mineral maps came back, Bennu stopped looking like a simple rubble pile and started to resemble the eroded core of a much larger, wetter world. An early analysis of the returned material found a type of rock that mirrors the composition of Asteroid Bennu’s surface but formed in the presence of liquid water, hinting that its parent body was once an ocean world. Microscopic structures in the rock, captured in “View larger” images, show alteration patterns that only make sense if water once percolated through the minerals as the young Solar System was cooling. That picture is reinforced by the detection of hydrated minerals and salts that would have crystallized out of briny fluids.

Those clues line up with the idea that Bennu is a fragment from a long-lost salty world that orbited in the early Solar System before being shattered. A separate analysis notes that a type of rock in the sample matches material seen as the Asteroid Bennu is sweeping past Earth, strengthening the case that the returned grains are representative of the whole body. Together, these findings suggest that Bennu’s chemistry was shaped inside a larger object where ice melted, rock altered and salts concentrated, long before the asteroid was broken apart and its fragments sent wandering.

Sugars, “space gum,” and a full RNA toolkit

The most headline grabbing surprise is chemical, not geological. A team of Japanese and US scientists has identified the bio essential sugars ribose and glucose in samples of asteroid Bennu, a result that would have been controversial if it had come from a meteorite that fell through the atmosphere. These sugars are central to modern biochemistry, with ribose forming the backbone of RNA and glucose serving as a key energy source and a building block for more complex carbohydrates. In the Bennu grains, they sit alongside other organics that can store energy and catalyze biological reactions, suggesting that complex carbon chemistry was already underway in small bodies before planets finished forming.

Those sugars are part of a broader pattern that has made asteroid science “even sweeter.” Scientists have reported that ribose and glucose were found in the sample brought to Earth in 2023, and that these sugars, together with previously detected nucleobases and phosphates, show that a full suite of RNA building blocks existed in Bennu. One detailed report from NASA’s News & Events section notes that “all five nucleobases used to store genetic information in DNA and RNA are present in Bennu,” tying the sugars to a broader set of Sugars and bases that look uncannily like the toolkit life uses today.

Alongside the sugars, researchers have flagged a sticky, polymer like material that has been nicknamed “space gum.” Samples taken from the asteroid Bennu contain this unusual substance along with organics that include nitrogen carbon compounds and tiny particles that predate the Solar System. One analysis of NASA’s asteroid sample notes that these findings sharpen the picture of how the Solar System formed, because such complex organics and even “space plastic” like material are being detected in pristine asteroid material for the first time, as highlighted in a NASA focused report.

Amino acids, salt water, and ancient stardust

The Bennu sample does not stop at sugars and nucleobases. Fourteen of the 20 amino acids that life on Earth uses to make proteins have been identified in the Bennu grains, along with chemical precursors to biomolecules like DNA and RNA. That tally is striking because it covers a broad swath of the amino acid “alphabet,” not just one or two simple species that could be dismissed as contamination. A separate overview of the mission’s results notes that these amino acids sit alongside ammonia and levels of formaldehyde that support an explanation in which the source of life on Earth could have come from asteroid impacts that contained life’s basic ingredients, as described in a summary of how asteroids offer scientists clues to life on Earth.

Water, the other pillar of habitability, also shows up in the Bennu story. Scientists analyzing the sample have discovered traces of salt water locked inside minerals, with Tim McCoy of the Tim led study emphasizing that these inclusions record briny fluids that once flowed through Bennu’s parent body. Another analysis describes how NASA’s OSIRIS mission revealed presolar grains in Bennu, tiny particles formed around ancient stars that were later incorporated into the asteroid. These grains, along with carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen carbon compounds, turn the sample into a layered record of processes that stretch from stellar nurseries to ocean like worlds and finally to near Earth space.

Researchers who have spent their careers studying meteorites are unusually confident about these results. One detailed account of the lab work quotes scientists saying “we can trust these results,” noting that in the samples from Bennu the researchers stumbled on some surprises, including exceptionally high concentrations of certain organics that are hard to explain without invoking aqueous chemistry. Another overview of the mission’s News & Events coverage notes that a second paper in the same research package describes how Bennu’s young parent asteroid warmed, allowing water to circulate and alter rock, a process that is summarized in a NASA release.

What Bennu tells us about life’s reach

More from Morning Overview