Physicists have assembled one of the largest and most intricate time crystals yet, using IBM’s latest quantum hardware to push a once-theoretical phase of matter into a new regime of scale and control. By arranging more than a hundred quantum bits into a carefully choreographed pattern of motion, the team has turned an abstract idea into a working laboratory system that behaves in ways ordinary materials never could. The result is not just a record-setting experiment, but a proof of concept for how quantum computers themselves might evolve into platforms for exploring exotic physics.

Time crystals were first proposed as structures that repeat in time rather than space, defying the intuition that a system driven by a regular pulse should simply follow that rhythm. Building a large, stable version inside a programmable processor shows how far quantum engineering has come in a short span, and hints at applications that range from more reliable quantum memories to new kinds of sensors and materials.

What a time crystal is, and why this one matters

At its core, a time crystal is a collection of interacting particles that settle into a pattern of motion that repeats at a different tempo than the external drive that keeps it going. Instead of absorbing energy and heating up, the system locks into a rhythm that is stable and robust, a kind of temporal order that breaks the symmetry of the driving clock. Researchers describe these states as fragile, because even small errors or unwanted interactions can destroy the delicate timing that defines them, which is why early demonstrations involved only a handful of quantum elements.

According to IBM’s own description of its work on time crystals, until recently it was only possible to probe such phases in small, highly controlled setups that did not resemble the messy, many-body systems found in nature. The new experiment changes that balance by using a quantum-centric supercomputing architecture to host a much larger, open-ended quantum system that can evolve for many cycles without losing its characteristic order. That shift from toy models to complex dynamics is what makes this particular time crystal scientifically significant.

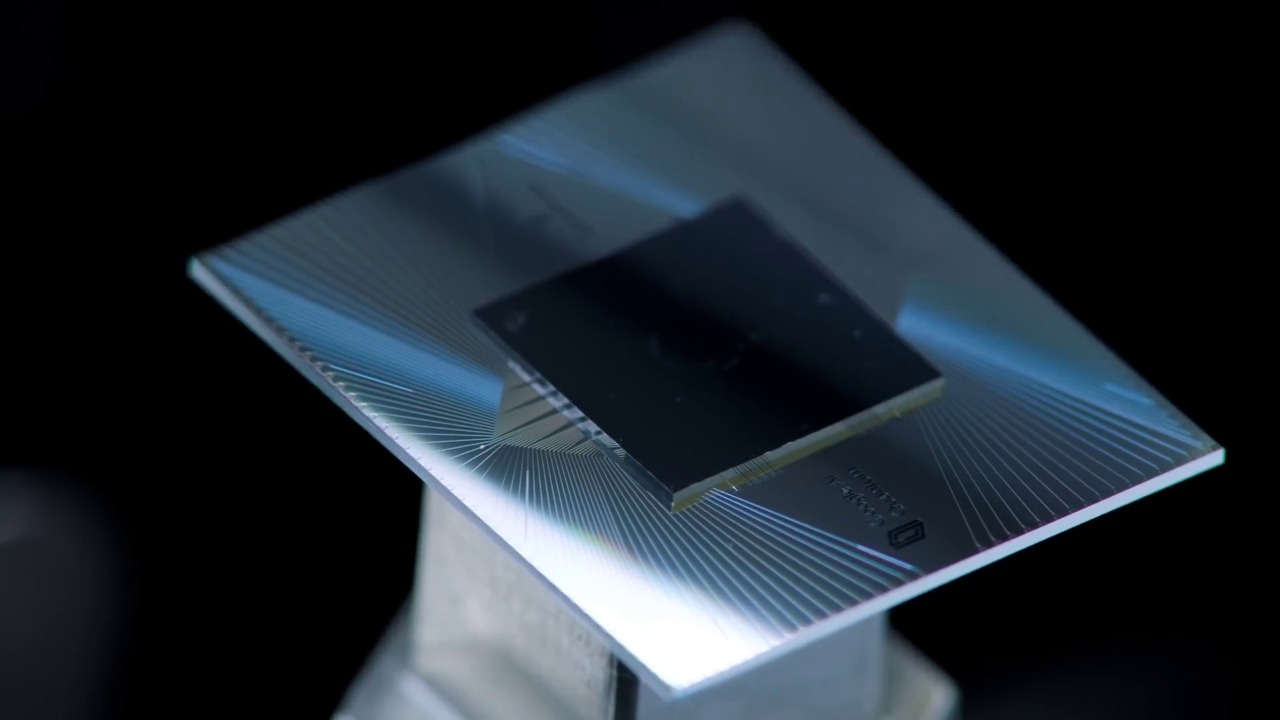

Inside the 144-qubit build on Quantum Heron

The latest advance centers on IBM Quantum Heron, a chip designed to offer cleaner, more reliable qubits that can be wired into larger patterns of interaction. Using Heron, the team constructed a 144-qubit, two-dimensional time crystal, a scale that moves the field beyond linear chains and into genuine quantum materials territory. In two dimensions, signals can propagate along multiple paths, interference effects become richer, and the interplay between local disorder and global order can be tuned in ways that one-dimensional systems simply cannot support.

Reports on the experiment describe how the researchers programmed the chip with a periodic sequence of quantum gates that, when repeated, caused the qubits to oscillate with a period that was a multiple of the drive, a hallmark of time-crystalline behavior. One account notes that the device used is part of IBM’s Heron chip family, which is engineered to reduce noise and crosstalk between qubits so that complex patterns can persist for longer. Another summary emphasizes that the work was carried out on IBM Quantum Heron hardware that is already integrated into a broader quantum computing stack, rather than on a one-off physics experiment, which underscores how quickly research-grade capabilities are migrating into general-purpose platforms.

Error mitigation and the path to “one of the largest” time crystals

Scaling up a time crystal from a few qubits to more than a hundred is not just a matter of adding more hardware; it requires taming the errors that accumulate as the system evolves. The team behind the new result leaned on advanced error mitigation techniques that estimate and subtract the impact of noise, allowing the underlying quantum signal to emerge more clearly from imperfect hardware. One detailed account explains that the researchers used new methods to reduce uncertainty in the quantum results, which in turn made it possible to verify that the oscillations were truly subharmonic and not artifacts of measurement.

Descriptions of the work repeatedly refer to the device as one of the time crystals ever created, a claim that rests on both the number of qubits involved and the complexity of their connectivity. IBM’s own technical blog on quantum-centric supercomputing frames the experiment as a demonstration of how classical control systems and quantum processors can work together to stabilize exotic phases of matter. By combining sophisticated calibration, real-time feedback, and post-processing, the researchers effectively extended the lifetime of the time crystal far beyond what raw hardware performance would allow.

From toy models to complex quantum matter

What sets this experiment apart is not only its size, but also the richness of the dynamics it can host. Earlier time crystals were often realized in one-dimensional chains where each qubit interacted mainly with its nearest neighbors, which limited the range of phenomena that could be explored. In contrast, the new 144-qubit, two-dimensional structure allows signals to move in more complex patterns, with interference and localization effects that resemble those in real materials. One report on today’s quantum computers stresses that large, programmable devices are now capable of simulating open-ended quantum systems that were previously out of reach.

Researchers involved in the project describe it as a step toward exploring phases of matter that have no classical analog, using quantum processors as laboratories for condensed-matter physics. A summary from a European research center notes that the work helps show how such systems could eventually be used to study semiconductors with many technological applications, by mimicking their behavior in a highly controllable environment. In that view, time crystals are not just curiosities, but benchmarks for how well quantum hardware can reproduce and extend the physics of complex materials.

What scientists hope to learn next

For the physicists who built it, the new time crystal is both a destination and a starting point. One detailed account explains that Scientists have successfully engineered a time crystal exhibiting unprecedented complexity within a quantum computer, and that this accomplishment opens new avenues for scientific discovery. By tuning the interactions and drive patterns, they can now ask how time-crystalline order competes with other phases, how it responds to disorder, and whether it can coexist with useful information-processing tasks on the same chip.

There is also a broader architectural lesson in how the experiment was put together. A separate description of the work highlights that researchers created a large, complex time crystal to showcase how quantum and classical hardware resources work together, which is central to IBM’s vision of quantum-centric supercomputing. As more powerful chips like IBM Quantum Heron come online, I expect to see time crystals used as stress tests for hardware and algorithms alike, revealing where noise still creeps in and where new control techniques are paying off. The latest result shows that even in a noisy, imperfect world, it is possible to carve out islands of order in time, and to use them as tools for understanding the quantum universe.

More from Morning Overview