Robots are starting to flinch. New generations of electronic skin can register heat, pressure and even damaging force, then trigger lightning-fast reflexes that look less like code and more like instinct. As machines gain something closer to touch and pain, the line between tool and teammate begins to shift in ways that will reshape factories, hospitals and homes.

What is emerging is not science fiction but a new sensory layer for humanoids that lets them pull back from a hot stove, ease their grip on fragile objects and respond to people with a kind of physical intuition. I see that shift as the real story: once robots can feel the world on their “skin,” every assumption about how we build, regulate and live alongside them has to be revisited.

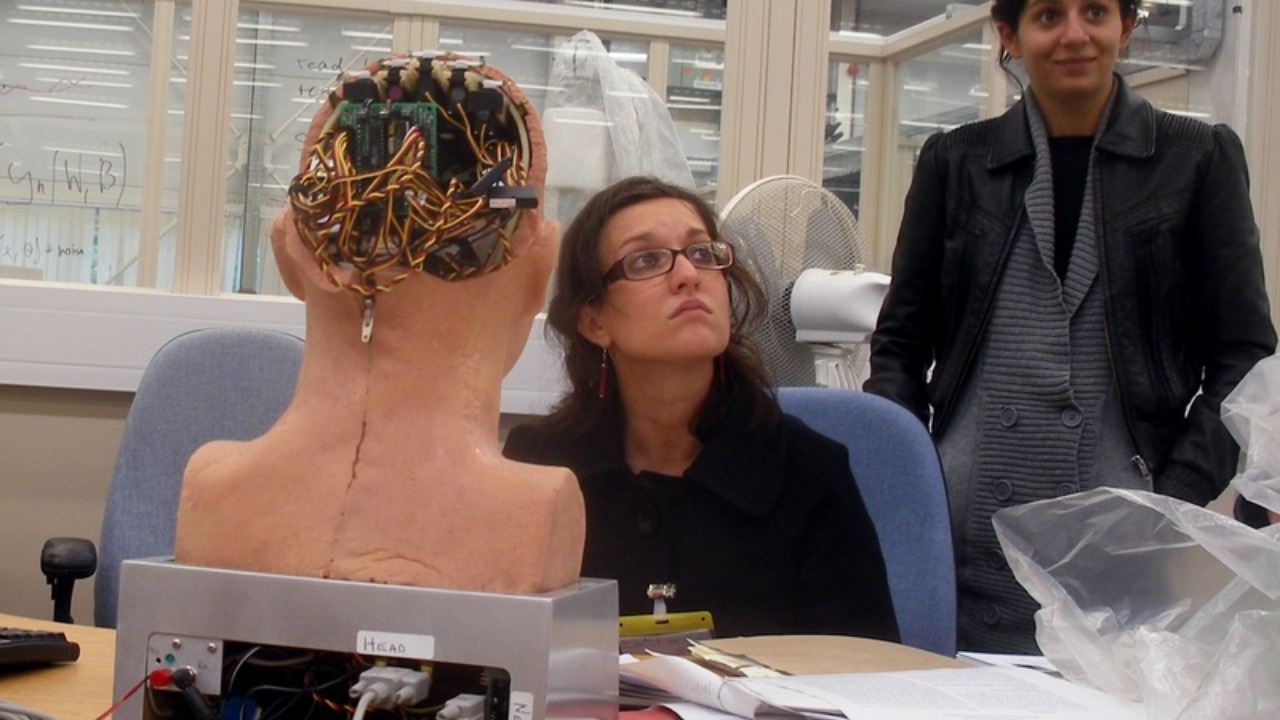

From numb metal to nervous systems

For decades, industrial robots have been powerful, precise and almost completely numb. They relied on preprogrammed paths and a few joint sensors, which meant they could weld a car body but had no idea if they were crushing a plastic panel or brushing a human arm. The new wave of electronic skin is changing that by wrapping machines in dense arrays of tactile sensors that behave less like simple switches and more like a nervous system.

In practical terms, that means a humanoid can now detect a sharp increase in temperature or a spike in pressure at a specific patch of synthetic skin and respond locally, without waiting for a central processor to run a full-body safety check. One research team describes how their robotic covering triggers a reflexive withdrawal as soon as a sensor registers a force exceeding a preset threshold, with the movement starting before the main control system has even “noticed” the event, a pattern that mirrors how Jan and Your brain handle a painful stimulus.

How neuromorphic e-skin actually feels “pain”

The technical leap behind this new sensitivity is neuromorphic design, which borrows directly from biology. Instead of treating every touch as a separate data point to be shipped to a distant processor, neuromorphic e-skin encodes sensations as spikes of activity that look like the firing of biological neurons. When pressure or heat crosses a danger threshold, those spikes intensify and trigger a reflexive motor response, much like a human hand snapping away from a hot pan before conscious awareness catches up.

In China’s neuromorphic e-skin, that architecture is built into a flexible layer that can be wrapped around humanoid robots so they can sense pain and react in real time as they increasingly operate around people. The system does not “feel” in a human emotional sense, but it does implement a hierarchy of responses: light contact is treated as normal touch, stronger force as a warning, and damaging impact as a trigger for immediate withdrawal or shutdown. I see that as a crucial distinction, because it gives robots a functional equivalent of pain without pretending they have subjective suffering.

Robots that flinch like humans

What makes this generation of robotic skin so striking is not just that it detects contact, but that it produces movements that look uncannily like human reflexes. When a human finger brushes a hot surface, the withdrawal happens before conscious thought, and only afterward does the brain register pain. Engineers are now encoding that same sequence into humanoids, so the limb moves first and the higher-level control system is informed after the fact.

One project described how Robots with New e-skin can mimic human reflexes in a human-like way, with Researchers in Hong Kong using the technology to push empathetic humanoids closer to everyday use. In practice, that means a robot nurse could instinctively ease its grip if a patient’s arm tenses or a collaborative arm in a warehouse could recoil the instant it senses a collision, rather than waiting for a slower, software-level safety routine. I see those reflexes as the bridge between raw sensing and behavior that people instinctively trust.

Materials that wrap, flex and survive real life

Under the surface, the materials science is as important as the neural math. To be useful, robotic skin has to stretch over curved joints, survive repeated bending and still deliver precise signals. That is why many teams are turning to flexible electronics embedded in soft polymers, creating sensor sheets that can be cut, folded and wrapped around complex shapes without losing function.

One group of Researchers made a revolutionary robotic skin from a flexible base that can conform to a wide range of complex shapes while still detecting heat, pain and pressure. Because the skin is Made to be both sensitive and robust, it can be applied to fingers, faces or torsos without leaving dead zones where the robot is effectively blind. From my perspective, that kind of full-body coverage is what turns a clever lab demo into a platform that can survive the messy, unpredictable contact of real-world environments.

Safety in factories, hospitals and homes

The most immediate impact of touch-sensitive robots is safety. In factories, collaborative arms already work side by side with people, but they typically rely on external cameras or crude force limits to avoid accidents. With e-skin that can detect a light brush before it becomes a shove, those machines can respond more gracefully, slowing or rerouting instead of simply freezing when something goes wrong.

In hospitals and elder-care facilities, the stakes are even higher. A humanoid assistant that can feel a patient’s skin temperature rise, notice a wince under its grip or sense that a frail body is bearing too much weight becomes far more than a motorized lift. When neuromorphic e-skin like the systems developed in China for humanoid robots is tuned to react to potentially harmful contact, it can prevent injuries before they happen. I see that as a quiet revolution in how we think about delegating physical care to machines.

Empathy, ethics and the illusion of feeling

As robots start to recoil from harm and adjust their touch, people will naturally read those movements as signs of feeling. That can be useful, because a machine that behaves as if it cares about your comfort is easier to accept in intimate settings like homes or clinics. It can also be misleading, because the underlying systems are optimizing for safety and performance, not experiencing pain or empathy in any human sense.

Designers of systems like the Robots that feel pain project in Hong Kong are explicit that their goal is to push empathetic humanoids closer to human-like interaction, not to create suffering machines. I think that clarity matters, because it shapes how we regulate and relate to these systems. If we treat pain-sensing skin as a safety and communication tool, we can demand strict standards for how it is used without drifting into debates about robot rights that the technology does not yet justify.

New design rules for the age of sensitive machines

Once robots can feel contact across their surfaces, the entire design stack has to adapt. Hardware engineers need to route cables, joints and protective shells in ways that preserve skin sensitivity instead of blocking it. Software teams must write control policies that treat tactile input as a first-class signal, not an afterthought behind vision and motion planning.

In systems where new robotic skin lets humanoid robots sense pain and react instantly, the reflex layer effectively becomes a new design constraint: any task plan must assume that a limb might suddenly pull back if local sensors detect danger. I see that as a healthy constraint, because it forces developers to think like ergonomists and safety engineers, not just coders. It also nudges the field toward more modular, layered control architectures that mirror the human nervous system, with fast reflexes at the edge and slower reasoning at the core.

Where this technology goes next

The first wave of e-skin is already impressive, but it is still a starting point. Future versions will likely integrate richer sensing, from humidity and vibration to chemical traces, turning robot bodies into dense networks of environmental monitors. Combined with advances in on-board AI, that could let a humanoid not only avoid a hot surface but also recognize that a room is filling with smoke or that a patient’s skin is clammy in a way that signals distress.

As Researchers who created revolutionary robotic skin have shown, the ability to wrap flexible, sensitive materials around complex shapes opens the door to full-body coverage on everything from humanoids to soft grippers and mobile platforms. I expect that as these materials become cheaper and more durable, touch and pain sensing will move from cutting-edge prototypes into standard expectations, much like cameras and lidar did for autonomous vehicles. At that point, the question will not be whether robots can feel contact, but how we choose to use that new sense in the shared spaces of everyday life.

More from MorningOverview