Thermodynamics was built to describe steam engines and stars, yet the same equations now sit at the heart of quantum computers and nanoscale devices. As physicists push into regimes where individual particles and fragile superpositions matter, they are discovering that the old rules need careful revision rather than blind application. I see a field quietly rebuilding one of physics’ most trusted frameworks so it can survive contact with the quantum world.

From steam engines to single qubits

The classical laws of thermodynamics were forged in the nineteenth century to explain heat, work, and efficiency in bulk matter, not in systems made of a handful of atoms. Those laws assume that energy and entropy can be treated as smooth, averaged quantities, which works for a coal plant or a car engine but starts to wobble when the “working fluid” is a single trapped ion or a superconducting qubit. As researchers design quantum heat engines and refrigerators that operate on just a few energy levels, they are finding that fluctuations, measurement back‑action, and coherence all force a rethink of what counts as heat, work, and irreversibility in the first place.

In recent work on quantum thermodynamics, theorists have begun to formalize these questions by treating energy exchanges as inherently probabilistic and by tracking how information and entropy flow through microscopic processes. One line of research, highlighted in a report on efforts to rewrite thermodynamics for quantum systems, treats coherence and entanglement as resources that can be spent or conserved much like free energy. Instead of a single second law, the theory yields a family of constraints that depend on how much control an experimenter has over individual quantum states, a shift that turns the old macroscopic bookkeeping into a far more granular accounting of what is thermodynamically allowed.

Measuring “quantumness” as a thermodynamic resource

Recasting thermodynamics for the quantum era is not just a matter of new equations, it also demands new instruments that can tell when a system is behaving in a genuinely quantum way. Traditional thermometers infer temperature from the average motion of many particles, but in a quantum device the key question is often how much coherence or entanglement survives in the presence of noise. That has led experimental groups to design protocols that treat “quantumness” itself as a measurable quantity, something that can be dialed up, degraded, and even traded off against energy and entropy.

One experiment described as a kind of thermometer for measuring quantumness uses carefully prepared quantum states to probe how strongly an environment disrupts superpositions. By watching how interference patterns fade as the system interacts with its surroundings, the researchers can assign a numerical value to the degree of coherence, much as a conventional thermometer assigns a temperature. In practice, that means engineers can characterize how “hot” a given noise source is in quantum terms, then redesign hardware and control pulses to keep delicate states in the low‑entropy regimes where quantum computers and sensors actually outperform their classical rivals.

Information, entropy, and the legacy of classical theory

Even as quantum experiments proliferate, the conceptual backbone of thermodynamics still rests on classical ideas about entropy and information that were sharpened long before anyone could manipulate single atoms. The modern view that information has physical consequences, and that erasing a bit of data carries an unavoidable entropy cost, grew out of debates about Maxwell’s demon and the statistical nature of the second law. Those arguments are now being revisited in light of quantum information theory, which treats states as vectors in a Hilbert space and entropy as a measure of uncertainty over those states.

Foundational texts on statistical mechanics, such as the detailed treatments collected in classic monographs on thermodynamic formalism, laid out how macroscopic irreversibility emerges from microscopic dynamics under assumptions of randomness and coarse‑graining. Quantum thermodynamics keeps that statistical spirit but replaces classical probabilities with density matrices and quantum channels, which encode both populations and coherences. The result is a hybrid language in which entropy production can be split into classical and quantum parts, and where information‑theoretic quantities like relative entropy and mutual information become the natural tools for tracking how measurements, feedback, and decoherence reshape the thermodynamic landscape.

Quantum devices as laboratories for new laws

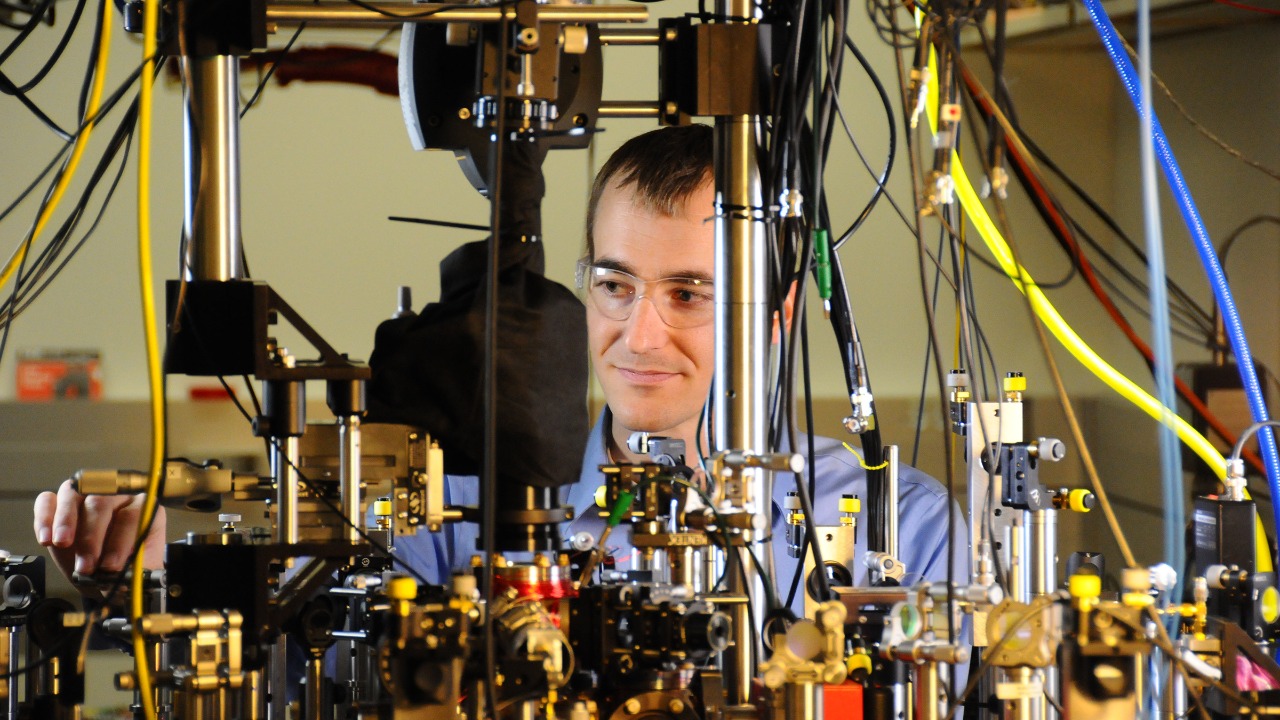

The most convincing tests of any revised thermodynamic framework will come from hardware that operates squarely in the quantum regime, where individual qubits and photons can be prepared, manipulated, and read out with high fidelity. Quantum processors, trapped‑ion chains, and superconducting circuits already function as small, programmable many‑body systems, which makes them ideal laboratories for exploring how energy, entropy, and information interact when coherence is a limited resource. In these platforms, researchers can implement microscopic heat engines, feedback‑controlled demons, and non‑equilibrium protocols that would be impossible to realize in a bulk material.

At the same time, the broader ecosystem of quantum and AI benchmarks is starting to treat thermodynamic‑style metrics as part of system evaluation, even if only implicitly. In one evaluation record for large models, for example, the performance of the system labeled “Nous‑Hermes‑2‑Mixtral‑8x7B‑DPO” is logged in a JSON file within a benchmarking repository, a reminder that even in classical AI, researchers are increasingly attentive to resource use, efficiency, and performance trade‑offs. As quantum devices mature, similar logs will likely track not only logical error rates and gate counts but also energy dissipation, entropy production, and the thermodynamic cost of error correction, turning abstract laws into concrete engineering constraints.

Crossing disciplines: from physics to computation and design

One of the striking features of the current thermodynamic rethink is how quickly it spills beyond physics into computation, design, and even creative practice. The same logic that treats information as a physical quantity also invites comparisons between physical systems and algorithms, where complexity, randomness, and structure all carry energetic implications. In software security, for instance, low‑level analyses of program behavior, such as the detailed reverse‑engineering notes preserved in a technical gist on binary internals, echo thermodynamic thinking by tracking how state spaces are explored and constrained.

Design theorists have likewise borrowed thermodynamic metaphors to describe how creative systems generate and dissipate structure. Miguel Carvalhais, in a study of procedural art and generative systems, treats computational processes as engines that transform randomness into form, a perspective laid out in his extensive analysis of creative computation. In that view, entropy is not just a measure of disorder but a reservoir of potential variation that artists and designers can harness, much as physicists harness thermal fluctuations. As quantum devices enter the creative toolkit, those metaphors may become literal, with artists directly manipulating superpositions and entanglement as raw material.

Brains, binding, and thermodynamic metaphors

The effort to update thermodynamics for quantum systems also resonates with long‑running attempts to understand how brains integrate information across space and time. Neuroscientists studying cortical dynamics often describe neural activity in terms of energy landscapes, attractor states, and phase transitions, all concepts that originated in statistical physics. When they ask how distributed firing patterns give rise to unified perceptions or decisions, they are effectively asking how a high‑dimensional system reduces its entropy to produce coherent behavior.

Some theoretical work on cortical integration explicitly frames this problem as one of binding across multiple levels of description, from biophysical processes to psychological states. In a detailed set of hypotheses about cortical binding, Alfredo Pereira Junior and collaborators describe how synchronized neural assemblies might integrate information while still obeying physical constraints. Although their framework is not explicitly quantum, it leans on the same intuition that complex systems must manage flows of energy and entropy to maintain organized patterns, an intuition that quantum thermodynamics now refines at the level of individual quanta.

Learning curves and conceptual obstacles

For students and researchers trained on classical thermodynamics, the shift to quantum thinking can feel like a conceptual phase transition of its own. Familiar quantities such as temperature and entropy acquire new, operator‑valued definitions, while intuitions about trajectories and microstates give way to amplitudes and measurement outcomes. Making that leap requires not only mathematical fluency but also a willingness to revise mental models that may have been stable since undergraduate courses in heat and work.

Educational research on how people adapt to new scientific paradigms underscores how demanding that process can be. Barbara Oakley, in her work on cognitive strategies for mastering difficult subjects, emphasizes the importance of alternating focused and diffuse modes of thinking, a point she develops in her discussion of how learners break through obstacles. Quantum thermodynamics, with its blend of abstract linear algebra and concrete physical intuition, is exactly the kind of domain where such strategies matter. As the field matures, I expect more structured curricula and visual tools to emerge, helping the next generation internalize ideas like quantum work, fluctuation theorems, and resource theories without treating them as mere formal curiosities.

Engineering, pedagogy, and the road ahead

Rewriting thermodynamics for the quantum age is not only a theoretical project, it is also an engineering and pedagogical challenge that will shape how future technologies are built and understood. Engineers who design nanoscale devices already confront situations where classical approximations fail, such as heat transport in molecular junctions or noise in superconducting circuits. Technical manuals on applied thermodynamics, including detailed treatments of heat and mass transfer, provide the macroscopic tools for handling such problems, but they rarely account for coherence or entanglement. Bridging that gap will require new design rules that treat quantum resources as carefully as they treat temperature gradients and material properties.

On the conceptual side, scholars in fields like interaction design and media theory are beginning to frame computational systems as thermodynamic actors that transform inputs, randomness, and user behavior into structured outputs. Miguel Carvalhais, in a separate reflection on creative practice and systems thinking, argues that designers must understand how processes generate and dissipate complexity, a theme he develops in his essay on aesthetics and computation. As quantum devices move from laboratories into commercial products, that systems view will become more literal, with product teams forced to account for cooling budgets, error‑correction overhead, and the energetic cost of maintaining low‑entropy quantum states. The emerging quantum thermodynamic framework will not just tidy up the equations, it will set the practical limits on what kinds of quantum technologies are feasible, affordable, and sustainable.

More from MorningOverview