Scientists have long wanted to watch iron(II) move inside living cells as it fuels metabolism, shapes immunity, and, in some cases, helps drive cell death. The headline promise of a biosensor that can track this motion in real time captures that ambition, but based on available reporting, such a tool remains an aspiration rather than a verified technology. What researchers do have today are indirect probes, imaging strategies, and disease models that show why a truly specific iron(II) sensor would be transformative if and when it arrives.

In this piece, I focus on what is actually documented: how iron-dependent cell death connects to inflammation, why the lack of precise probes is such a bottleneck, and how advanced imaging in organoids hints at what real-time iron tracking might eventually look like. The result is less a product announcement than a reality check on the state of the science and the gap a future biosensor would need to fill.

Ferroptosis, inflammation, and the missing probe

Any discussion of iron(II) dynamics in living cells has to start with ferroptosis, a form of regulated cell death that depends on iron and lipid peroxidation. In inflammatory settings, ferroptosis-like processes can amplify tissue damage, turning a short-lived injury response into a prolonged, self-sustaining cycle. That feedback loop makes iron handling inside cells a central question for immunology and pathology, because the same metal that supports normal physiology can, in the wrong context, help drive chronic disease.

Researchers studying ferroptosis have made it clear that they are still working with imperfect tools. One group explicitly notes that ferroptosis has not yet been visualized in vivo because there is a lack of specific probes, a limitation that has severely constrained efforts to follow this iron-dependent death program inside living organisms. In their analysis of how ferroptosis-like cell death promotes and prolongs inflammation, they emphasize that this lack of visualization tools is not a minor technicality but a core obstacle to understanding how iron-related damage unfolds in real time.

Why a real iron(II) biosensor would matter

Given that gap, it is tempting to imagine a new biosensor that could directly report iron(II) levels in living cells with high spatial and temporal resolution. If such a device existed and were validated, it would allow scientists to watch iron(II) fluxes as cells respond to injury, infection, or metabolic stress, instead of inferring those changes from downstream damage or static snapshots. That kind of capability would change how we test hypotheses about iron’s role in cell death, oxidative stress, and tissue repair.

Right now, however, the available evidence does not confirm that a specific, real-time iron(II) biosensor has been built and deployed in the way the headline suggests. The ferroptosis work that highlights the lack of specific probes underscores how much of the field still relies on indirect markers, genetic perturbations, and chemical inhibitors to map iron’s role. Until a probe can selectively bind iron(II) in the crowded environment of a living cell, without being confused by iron(III) or other metals, claims about watching iron(II) move in real time remain aspirational and should be treated as unverified based on available sources.

Lessons from live organoid imaging

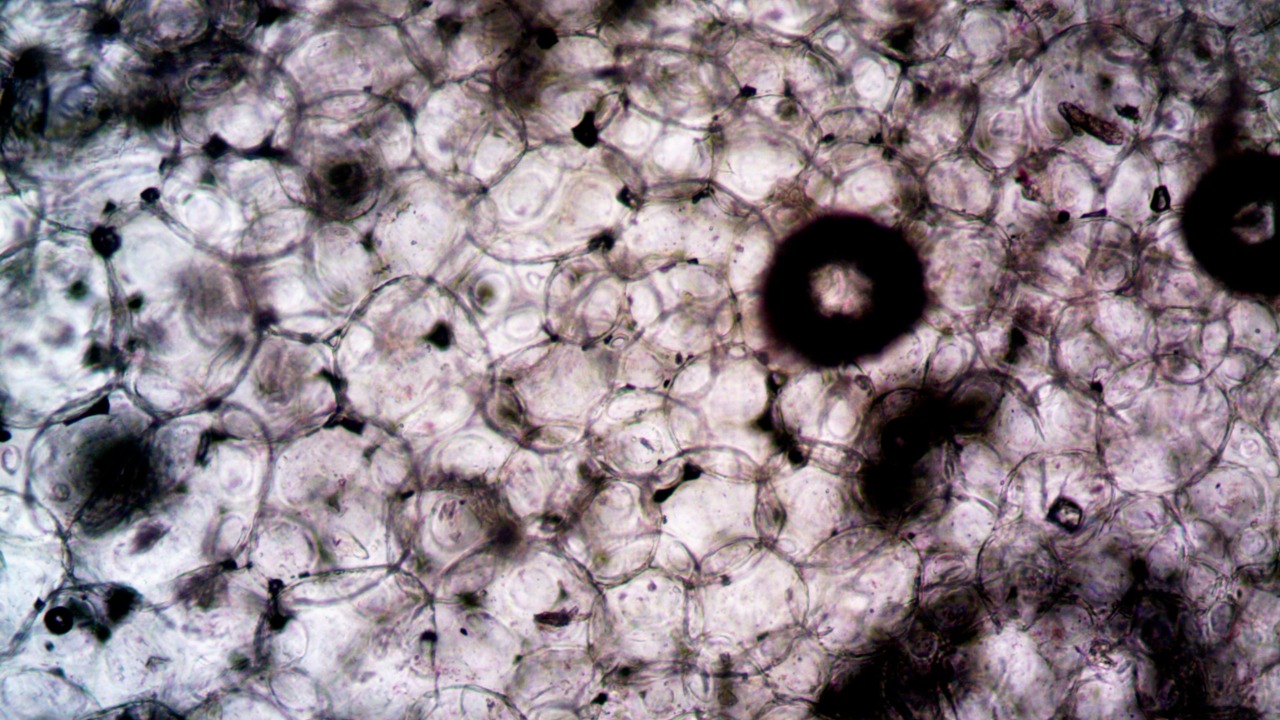

Even without a dedicated iron(II) sensor, advances in live imaging are showing what might be possible once such a tool is available. In a presentation on organoid imaging, foreign dimitriv, a professor at the tissue engineering and biomaterials imaging group at Ghent University the, describes how three-dimensional cultures can be monitored over time to reveal dynamic changes in structure and function. These live organoids, which mimic aspects of real tissues, are already being used to track cell differentiation, matrix remodeling, and responses to drugs in ways that traditional two-dimensional cultures cannot match.

The same imaging platforms that make it possible to follow organoid development could, in principle, host a future iron(II) biosensor. High-resolution microscopes, optimized light paths, and careful control of phototoxicity are all part of the infrastructure needed to watch any fast-moving signal inside living tissue models. What is missing is the iron-specific reporter itself. Until that exists, organoid imaging can show how cells behave under different iron conditions, but it cannot yet provide a direct movie of iron(II) molecules moving through the system.

From Drosophila wounds to human disease

Work in model organisms illustrates both the promise and the current limits of tracking iron-related cell death in vivo. In the ferroptosis study that highlights the lack of specific probes, the authors point to experiments by Davidson et al. that examined wounding in the Drosophila embryo. Those experiments linked ferroptosis-like mechanisms to the inflammatory response after injury, suggesting that similar pathways could be at play in more complex organisms. Yet even in this relatively simple system, the researchers had to infer ferroptosis from genetic and biochemical signatures rather than from a direct visualization of iron(II) activity.

Translating those insights to human disease will require tools that can bridge the gap between molecular detail and whole-organism context. A validated iron(II) biosensor could, in theory, be used to monitor how immune cells handle iron at a wound site, how neurons manage iron during neurodegeneration, or how tumor cells exploit iron metabolism to support growth. For now, though, such applications remain hypothetical. The Drosophila work and related studies show that ferroptosis-like death can shape inflammation, but they also underscore how much of that story is still being told through indirect evidence rather than direct observation of iron(II) in action.

The road ahead for iron imaging

Looking across these strands of research, the pattern is clear: scientists know that iron(II) is central to processes like ferroptosis and inflammation, they have sophisticated imaging platforms for live tissues and organoids, and they have model systems that reveal how iron-related cell death affects whole organisms. What they do not yet have, based on the sources available, is a specific, real-time biosensor that can track iron(II) itself inside living cells. Any claim that such a tool is already in hand, complete with defined design, functionality, and applications, is unverified and should be treated with caution.

That does not diminish the importance of the goal. On the contrary, the explicit acknowledgment that ferroptosis has not yet been visualized in vivo because of a lack of specific probes highlights how valuable a true iron(II) sensor would be. As imaging specialists refine live organoid platforms and disease biologists map iron-dependent pathways in models from Drosophila embryos to mammalian tissues, the field is effectively preparing the stage for such a technology. When a rigorously tested iron(II) biosensor finally arrives, it will plug into an ecosystem that is ready to use it, but until then, the most responsible position is to separate what is already demonstrated from what remains a compelling, and still unmet, scientific ambition.

More from Morning Overview