For the first time, humanity has proved it can deliberately shove a small world off course. NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test, better known as DART, turned a one‑ton spacecraft into a guided battering ram and showed that a kinetic impact can meaningfully change an asteroid’s motion. The mission was framed as a test, but its success has pushed planetary defense out of the realm of science fiction and into the domain of practical engineering.

The core idea is deceptively simple: if we can spot a hazardous asteroid early enough, we might only need a small nudge to make it miss Earth. By smashing into the moonlet Dimorphos, DART demonstrated how that nudge could work in practice, and it opened a new era in which deflecting a real threat is no longer a theoretical exercise but a problem of timing, politics, and preparation.

From thought experiment to hardware: how DART was built

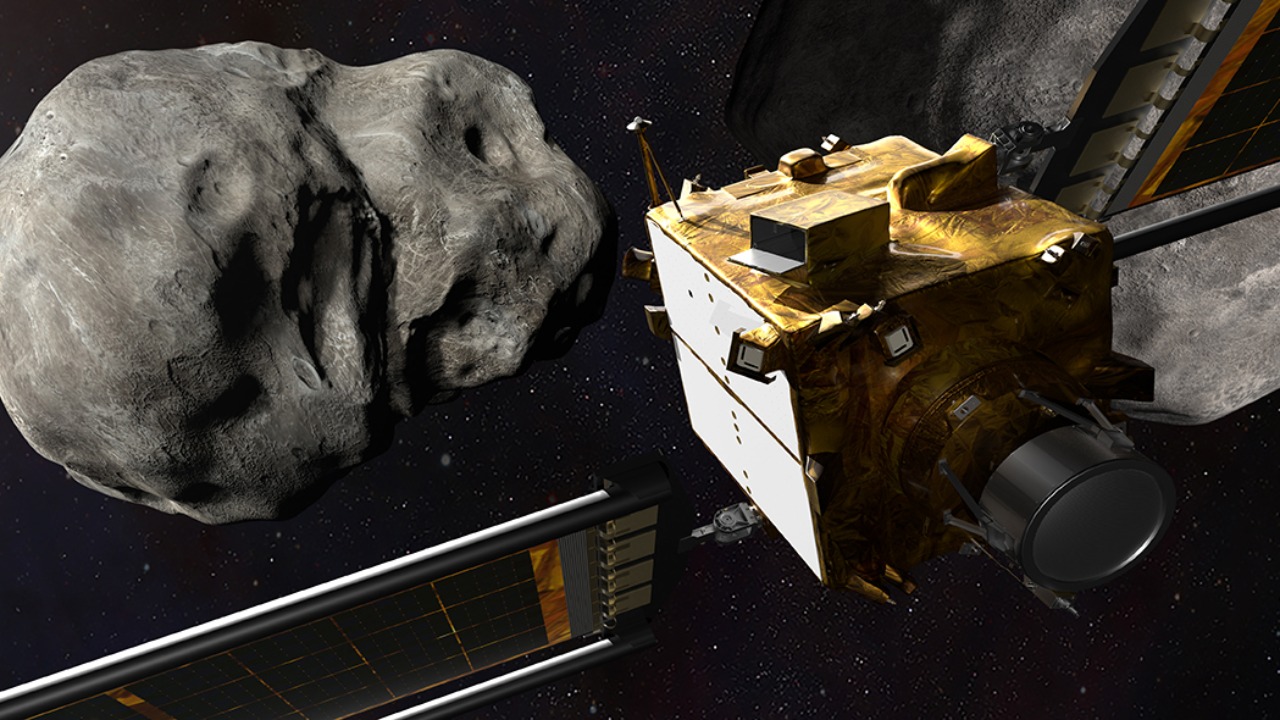

Planetary defense used to be a line in strategy documents, not a line item in hardware budgets. With DART, NASA committed to a full‑scale experiment, building a spacecraft specifically to test whether a kinetic impact could alter an asteroid’s orbit. The mission’s formal name, the Double Asteroid Redirection, signaled that this was not a science‑only probe but a deliberate rehearsal for deflecting a future threat. Engineers designed DART as a relatively simple, single‑purpose craft, but they paired it with sophisticated navigation software that could autonomously lock onto a tiny target in the final minutes before impact.

The target system, the binary pair Didymos and Dimorphos, was chosen precisely because it offered a safe, measurable way to test deflection. Dimorphos is a small moonlet orbiting the larger asteroid Didymos, so any change in its orbital period could be tracked without risking a stray rock on a new path toward Earth. Mission planners leaned on prior characterization of the system and on the broader context of NASA’s DART work to ensure that the experiment would be both dramatic and scientifically rigorous, while still posing no danger to the planet the mission was meant to protect.

Smashing Dimorphos: what actually changed

The key question for DART was not whether the spacecraft could hit Dimorphos, but whether that impact would significantly alter the moonlet’s orbit. Prior to the collision, Dimorphos circled Didymos once every 11 hours and 55 minutes, a rhythm measured through careful observations of the binary system’s brightness. After the impact, NASA used extensive analysis of follow‑up data to confirm that the orbital period had shortened, proving that the kinetic strike had delivered a measurable push. That change in timing, not the spectacular plume of debris, is what turned a dramatic crash into a successful technology demonstration.

Those measurements were not a matter of eyeballing before‑and‑after images. Teams relied on coordinated analysis of light curves and radar returns to track how Dimorphos’ motion evolved in the weeks following the impact. The result was clear: the orbit had shifted enough to show that a relatively small spacecraft, traveling at hypervelocity, could meaningfully change an asteroid’s trajectory. For planetary defense planners, that confirmation is the crucial proof that a similar technique could be used one day to deflect an Earth‑bound object, provided it is detected with sufficient warning time.

Inside the physics of a planetary shove

On paper, DART was a test of a simple momentum transfer, but the real physics turned out to be richer and more revealing. The mission was conceived as a kinetic impact experiment, with the spacecraft’s mass and closing speed delivering a direct impulse to Dimorphos. However, the plume of ejecta blasted off the surface effectively amplified that impulse, as material thrown backward gave the asteroid an extra kick in the opposite direction. Researchers have been unpacking these effects in detailed models, including work summarized in a DART study that examines how the impact dynamics inform broader planetary defense strategies and highlight remaining gaps in preparedness.

To understand the immediate aftermath, mission teams did not rely on the main spacecraft alone. A small companion probe, LICIACube, flew past Dimorphos minutes after impact and captured crucial views of the expanding debris cloud and evolving plume. Those images, combined with a network of ground‑based and space‑based telescopes, fed into photometric and radar observations that helped reconstruct how energy and momentum were distributed. The emerging picture is that rubble‑pile asteroids like Dimorphos can respond in complex ways to an impact, which is both a challenge for precise prediction and an opportunity to get more deflection than the spacecraft’s mass alone would suggest.

What we learned about Dimorphos itself

DART did more than move Dimorphos, it reshaped it. A detailed study of the system found that the impact changed not only the moonlet’s orbit but also its internal structure and exterior form. According to a Planetary Science Journal analysis, the asteroid’s orbit and shape both evolved, with Dimorphos taking on a more elongated configuration, described as being like a watermelon. That kind of global deformation indicates that the body is not a solid monolith but a loosely bound aggregate whose interior can flow and settle when disturbed.

Follow‑up work has gone further, suggesting that the impact may have caused material from the interior to migrate outward, altering the surface composition and texture. Simulations of the event, discussed in reshaping studies, point to a process in which the entire asteroid briefly behaved like a fluid body before settling into a new equilibrium. Learning how long Dimorphos takes to regain stability, as highlighted in separate research, offers a window into its internal structure, which in turn is vital for predicting how similar objects might respond to a future deflection attempt.

From one test to a planetary defense playbook

For all its drama, DART was only one piece of a broader strategy to protect Earth from hazardous objects. NASA’s planetary defense program now treats the mission as a foundational experiment that informs how to design future deflection campaigns. Official materials describe the Double Asteroid Redirection as a way to change an asteroid’s orbital path, and subsequent Analysis of the data has refined models of how much warning time and how many impactors might be needed for different threat scenarios. The mission’s success also strengthens the case for investments in sky surveys that can find dangerous objects early enough for such techniques to be viable.

Outside NASA, advocacy groups have folded DART into a larger narrative about humanity’s role in managing cosmic risk. One organization frames its work around three core enterprises, to Explore Worlds, Find Life, and Defend Earth, and highlights DART as the first planetary defense mission to test a method of deflecting an asteroid on course to hit Earth. Educational efforts have also seized on the mission, with resources explaining Science Behind NASA, the First Attempt at Redirecting an Asteroid and using DART’s images and data to bring orbital mechanics into classrooms.

The mission’s timeline underscores how quickly a focused project can move from concept to reality. The spacecraft was Launched in late 2021 and, after about 10 months of cruise, successfully collided with Dimorphos at 23:14 UTC. Mission materials describe it as NASA’s first full‑scale test of a kinetic impactor, and internal Oct briefings emphasize how the DART spacecraft, part of Double Asteroid Redirection, successfully carried out its mission. For me, the most striking legacy is that planetary defense is no longer an abstract promise. It is a set of tested techniques, grounded in real hardware and real data, that can be refined and scaled as we learn more about the small bodies that share our solar system.

More from Morning Overview