NASA spent roughly a billion dollars to send a car‑sized robot into the Sun’s atmosphere, and to get there it had to accelerate to about 400,000 mph, faster than any spacecraft in history. That extreme journey has now paid off with the closest images ever taken of our star and a trove of data from inside its outer atmosphere. Together, those measurements are reshaping what I, and many solar physicists, thought we knew about how the Sun works and how it affects Earth.

The Parker Solar Probe’s record‑setting flybys have revealed a dynamic, almost alien landscape of magnetic funnels, looping jets and “switchback” kinks in the solar wind that were invisible from afar. The mission is not just a stunt in speed or heat resistance, it is a practical attempt to understand the engine behind space weather that can knock out power grids, disrupt GPS and threaten astronauts.

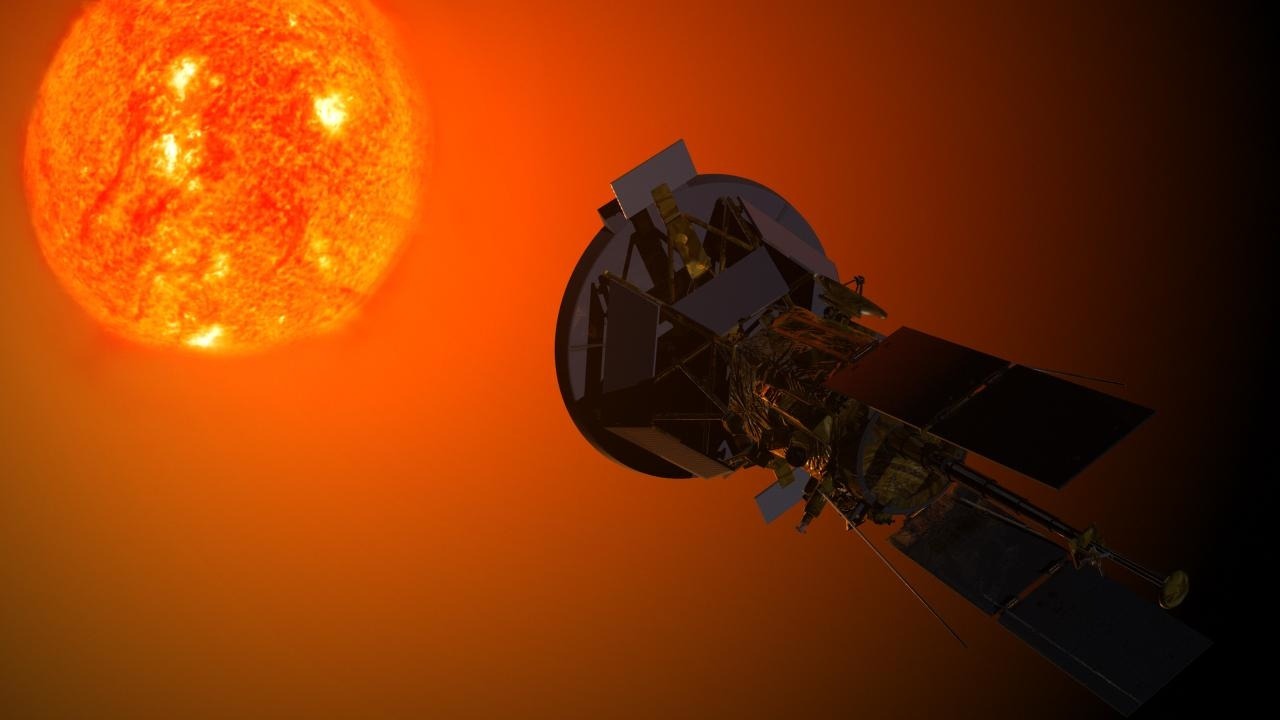

The fastest object from Earth, built to touch the Sun

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe is the first spacecraft designed to literally fly through the Sun’s outer atmosphere, the corona, rather than just observe it from a safe distance. The mission, part of the agency’s heliophysics program, launched in 2018 with a clear mandate to “touch the Sun” and sample the charged particles and magnetic fields that stream outward as the solar wind, a goal laid out in the core mission description. To survive, the spacecraft carries a 4.5-inch-thick carbon-composite shield that keeps its instruments protected from up to 2,500 degree conditions, a thermal barrier so unforgiving that even a few degrees of pointing error could be catastrophic, as engineers have explained in detail about the Parker Solar Probe. The result is a spacecraft that can stare directly at the Sun while its electronics operate at roughly room temperature.

To fall inward toward the Sun instead of slingshotting away, the probe had to shed much of Earth’s orbital momentum, a trajectory that required a powerful launch and repeated gravity assists. That path has turned it into the fastest object ever built on Earth, a status highlighted in technical overviews of the Parker Solar Probe. As it skimmed through the corona, the spacecraft reached about 400,000 MPH relative to the Sun, a figure that recent analyses of what It Took 400,000 M to Get There, Here is What NASA found near the Sun have emphasized when describing the probe’s extreme environment and the need to decode particle behavior with instruments like ALPS, as detailed in a Jan report.

Record-breaking flybys at 3.8 million miles

Over a series of looping orbits, Parker has dived closer and closer to the Sun, using Venus flybys to tighten its path. During its 24th close approach, NASA reported that the spacecraft matched its record distance of 3.8 m from the Sun’s surface, a proximity that puts it deep inside the corona and far closer than any previous mission, according to a detailed Jun mission update. Another summary of the mission’s closest pass underscores that this distance, achieved on a Thursday perihelion, represents a historic milestone in solar exploration and confirms that the spacecraft’s heat shield and guidance systems can withstand repeated plunges into this hostile region, as highlighted in coverage of the closest pass.

At those distances, the probe is not just skimming the edge of the corona, it is flying through the very region where the solar wind is accelerated and where explosive events like coronal mass ejections are still taking shape. NASA’s own science pages note that the mission carries a suite of instruments to measure fields, particles and waves, a capability summarized in the Scientific Instruments section of the mission overview. As the spacecraft repeatedly swings by such a massive and gravitationally intense object, it continues to pick up speed, a process that has been described in detail in reports on how, when it nears the Sun, the probe’s orbit tightens and its velocity climbs while its shield keeps the instruments operating at around room temperature, as explained in analyses of Dec flybys.

Jaw-dropping speeds and the closest images of the Sun

The raw speed of Parker’s orbit is staggering even by spaceflight standards. NASA has highlighted that the spacecraft now travels 690,000 km/h, or 430,000 m, which is about 0.064% of the speed of light, a benchmark that makes it the fastest spacecraft in history and underscores how strongly the Sun’s gravity pulls on a close‑passing object, as detailed in a Dec mission explainer. That velocity is not a mere record to brag about, it is what allows the probe to spend precious minutes inside the corona before racing back out, gathering high‑resolution measurements of plasma and fields that would be impossible from a slower, more distant orbit. Earlier mission notes also stress that the trajectory required high launch energy and careful planning to surpass the previous record holder, Helios‑2, a point that appears in technical descriptions of the trajectory.

Those close passes have now produced the closest images of the Sun ever obtained. NASA reports that Parker’s cameras captured views from just 3.8 m miles above the solar surface, revealing the corona in unprecedented detail and providing data that are essential to understanding how solar activity affects Earth, as summarized in a set of KEY POINTS. Visual explainers have showcased how, on its closest‑ever flyby, the probe recorded the Sun’s corona and the solar wind in fine structure, with NASA describing how these observations help trace how energy and particles move from the Sun into the solar system, a theme highlighted in Newly released graphics. Additional galleries from the mission team show the evolving structure of the corona and solar wind as seen by the probe’s cameras, with curated images that capture streamers, jets and the faint glow of dust near the Sun.

Magnetic funnels, switchbacks and a Solar wind U-turn

What those images and in situ measurements reveal is a Sun that is far more structured and turbulent than the smooth disk we see from Earth. Researchers analyzing the first five years of data have reported that magnetic funnels litter the sun’s surface, acting as channels that guide plasma into the solar wind and help explain how the corona is heated to millions of degrees, a result summarized in a comprehensive review of what the mission has discovered in its first looping orbits around the sun’s environment. Among the early surprises were strange flips, or switchbacks, in the magnetic field, where the solar wind’s direction briefly reverses before snapping back, a phenomenon that had been hinted at by earlier missions but only fully characterized once Parker flew through the region where these structures form, as detailed in the same Among the Probe findings.

More recently, the spacecraft has even watched the solar wind perform a kind of U‑turn. Imaging data show streams of charged particles that appear to bend back toward the Sun, a behavior that suggests complex interactions between the outflowing wind and the Sun’s magnetic field, as described in reports on a Solar wind ‘U-turn’ spotted by Parker Solar Probe. Those same observations note that the spacecraft also captured a coronal mass ejection exploding from our star, giving scientists a front‑row view of how such eruptions evolve close to their source, a perspective that is impossible from Earth‑orbiting observatories and that is further illustrated in broader coverage of the Parker Solar Prob results.

More from Morning Overview