When a NASA scientist finally cracked open a cache of 50-year-old lunar soil, the expectation was to refine old models, not overturn them. Instead, the ancient grains pointed away from a popular story about how Earth got its water and toward a harsher, drier picture of the early inner solar system. The surprise buried in that Moon dust is now reshaping how I think about everything from Apollo’s legacy to the stakes of the Artemis era.

The new work suggests that meteorites delivered far less of our planet’s oceans than many researchers once believed, and that the Moon’s surface has been quietly recording that history grain by grain. By tying together fresh analyses of Apollo cores, exotic lunar chemistry and the violent processing of regolith, I can see a narrative emerging in which the Moon becomes a forensic archive for Earth’s deepest past.

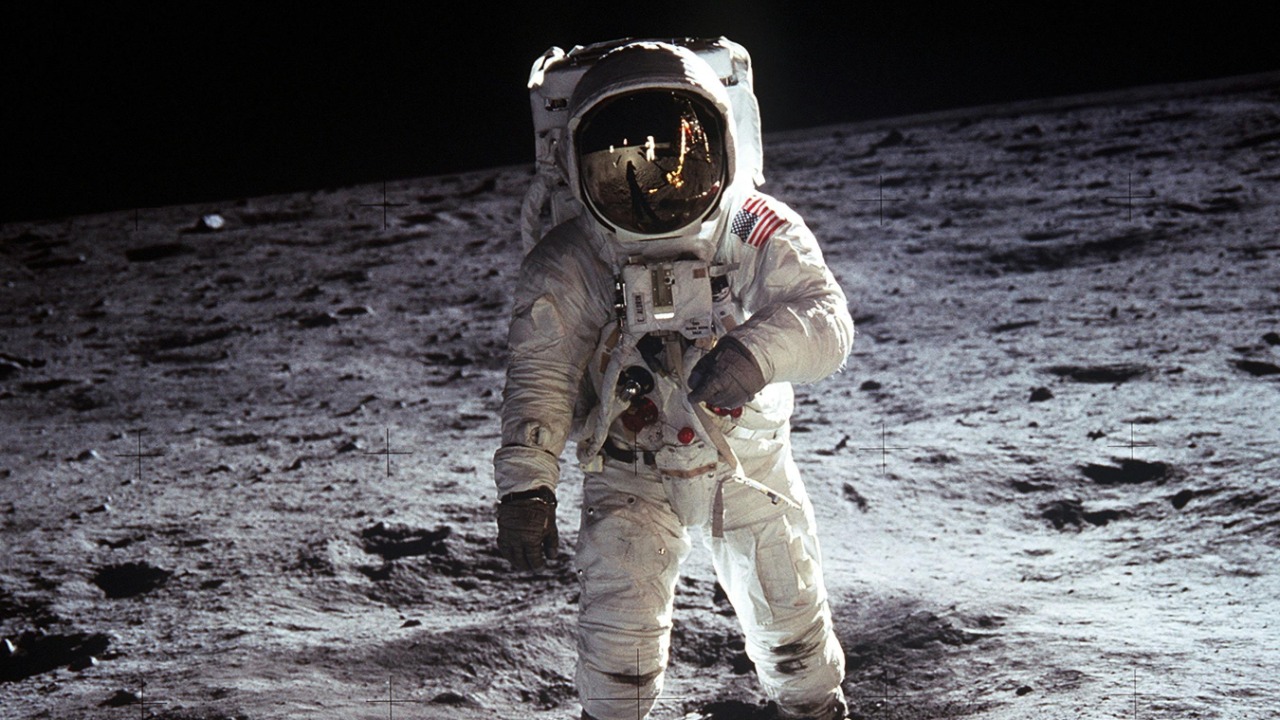

The 50-year-old sample that challenged Earth’s ocean story

The turning point came when a researcher at NASA revisited a sealed Apollo core that had been collected and then left largely untouched for roughly half a century. In the framing of the project, a NASA Scientist Looked was that the regolith held clues to whether meteorites could have supplied the bulk of Earth’s oceans. The analysis focused on how water-related signatures are preserved in lunar grains that have been bombarded by space for billions of years, and the result was stark: the contribution from meteorites over roughly four billion years is minimal. Instead of acting as a giant tanker fleet of ice, the rocks that slammed into the early Earth appear to have been a trickle, not a flood.

That conclusion matters because it undercuts a long-favored explanation for why our planet is so wet compared with its neighbors. The same study, led by a postdoctoral researcher, found that the lunar surface retains a detailed record of impacts and volatile delivery, yet the isotopic evidence in the regolith did not match what would be expected if meteorites had filled the oceans. The work, described as turning old theories upside down, reframes the Moon as a witness that contradicts the meteorite-dominated narrative and forces me to look harder at alternative sources, from deep mantle reservoirs to early gas-rich disks that may have fed both Earth and Moon before the worst of the bombardment.

How Tony Gargano and isotope fingerprints rewrote the script

The scientist at the center of this shift is Tony Gargano, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Johnson Space Center and the Lunar and Planetary Institute, whose work I see as a template for how to squeeze new science from old samples. new research led used the churned-up lunar soil as a natural laboratory for tracking how water-bearing particles interact with the surface. By treating the regolith as a stratified archive of impacts, solar wind and micrometeorite gardening, Gargano and colleagues could separate out different potential water sources and test how much each contributed over time.

The key to that separation was a sophisticated triple-isotope technique that acts like a chemical barcode for water. In coverage of the work, the method is described under the banner of THE ISOTOPE FINGERPRINT, which allowed the team to distinguish the “fingerprints” of ancient space travellers from other processes in the churned-up lunar soil. When those fingerprints were compared with the composition of Earth’s oceans, the mismatch was unmistakable. The study concluded that meteorites could account for only a small fraction of Earth’s total ocean volume, a result that dovetails with the earlier finding that their contribution over four billion years is minimal and that pushes me to consider more complex, multi-stage histories for planetary water.

NASA’s broader regolith campaign and the limits of meteorites

The Moon dust surprise did not emerge in isolation, and I see it as part of a broader campaign inside NASA to treat lunar regolith as a key to planetary evolution. In a detailed summary of this effort, Rachel Barry describes how scientists are using Apollo and Artemis-era samples to quantify the bombardment the Moon has experienced over billions of years and to test how efficiently meteorites can deliver and retain water. The conclusion that lunar regolith limits meteorites as a source of Earth’s water is grounded in that long-term perspective: the surface has been pummeled, yet the isotopic record still points to a relatively small net delivery of volatiles.

At the same time, other researchers are probing how the physical and chemical evolution of the soil itself affects what it can tell us. Work on why old Moon dust looks so different from fresh material shows that older soil samples are coated in nano-size iron particles created by the solar wind, a process that darkens the surface and alters its reflectance. Those findings, detailed in an analysis of why old Moon diverges from fresh regolith, highlight how space weathering can mask or modify the original signatures of impacts and volatiles. For me, that underscores why the 50-year-old sealed cores are so valuable: they preserve a less altered snapshot of the lunar environment, making their constraints on meteorite-delivered water even more compelling.

Exotic sulfur, hidden landslides and what they reveal about the Moon’s interior

While Gargano’s work focuses on water, other teams are using the same Apollo-era archive to uncover exotic chemistry that has no direct analogue on Earth. In one study, scientists revisited material collected when Apollo astronauts drove a 2-foot-long core tube into the surface after the Apollo 17 landing in the Taurus-Littrow valley. That effort, described as discovery 50 years, used modern instruments to identify an exotic sulfur-bearing component that had been invisible to earlier generations of researchers. The work explicitly notes that the story of the Moon’s interior, and by extension the early Earth-Moon system, looks very different once that hidden chemistry is taken into account.

The scientist leading that sulfur hunt, identified as Dottin, targeted grains whose textures suggested they had erupted with the host rock rather than being added later. Dottin explained that he was targeting sulfur that had a texture indicating it was erupted with the rock and not added through a different process, a strategy that helps isolate signals from the Moon’s mantle. In a complementary analysis, Dottin and his colleagues specifically analyzed portions of the drive tube sample that appeared to be volcanic rock from the Moon, using that material to infer conditions deep in the interior and to refine models of the early history of our solar system. For me, the fact that such exotic sulfur phases are different from anything we find on Earth reinforces the idea that the Moon’s mantle evolved along a distinct path, even though it shares a common origin with our planet.

The surprises are not limited to chemistry. When another sealed Apollo Moon sample was finally opened after 50 years, scientists found evidence of an extraterrestrial landslide preserved in the core. The sample, described as an Apollo Moon core that had remained untouched for decades, contained layers that could only be explained by a large-scale slope failure on the lunar surface. That kind of event reshapes local topography and redistributes regolith, which in turn affects how we interpret the stratigraphy of other cores. It also hints at a more dynamic Moon than the static, airless sphere often imagined, with mass wasting events that can bury or expose materials from different depths and ages.

More from Morning Overview