When astronomers announced Kepler-452b, they were not just adding another distant world to a growing catalog. They were pointing to a planet that orbits a star much like our own, in a region where liquid water could plausibly exist, and that looks uncannily familiar in its basic layout. For researchers hunting signs of biology beyond Earth, it is the closest thing yet to a controlled experiment on how life might arise around a Sun-like star.

Kepler-452b has quickly become shorthand for the idea that an “Earth-like” planet is no longer a theoretical construct but a measurable target. Its orbit, size, and stellar environment make it a benchmark for the next generation of telescopes and listening experiments that are now probing whether alien life has already taken root there.

What makes Kepler-452b so Earth-like?

The appeal of Kepler-452b starts with its orbit. It circles a star that closely resembles the Sun and does so at a distance that places it squarely in the so-called habitable zone, where temperatures could allow liquid water on a planetary surface. In classroom material on Exoplanets and the Search for Habitable, Kepler-452b is described as the first known planet to orbit a Sun-like star at roughly the same distance Earth does, about 1.05 astronomical units, which is close enough that its year and energy budget look familiar.

Physically, the planet is not a perfect twin, but it is close enough to earn the label “cousin.” NASA notes that NASA considers this world and its star the closest analog yet to Earth and the Sun, even though the planet itself is about 60% larger in diameter. That extra size likely means a higher surface gravity and potentially a thicker atmosphere, but it still places Kepler-452b in the category of “super-Earths,” planets that are bigger than Earth yet smaller than the ice giants like Neptune.

A bigger, older cousin in a familiar neighborhood

Kepler-452b orbits a star that is slightly older and a bit brighter than the Sun, which is why NASA’s discovery announcement framed it as a “bigger, older cousin” to our own planet. In that release, Scientists working with NASA explained that the Kepler Mission Discovers Bigger, Older Cousin to Earth by tracking tiny dips in starlight as the planet crossed its star. That same mission, described as Kepler Mission Discovers, helped push the tally of confirmed exoplanets into the thousands, but Kepler-452b stood out because its orbit and star looked so much like our own system’s layout.

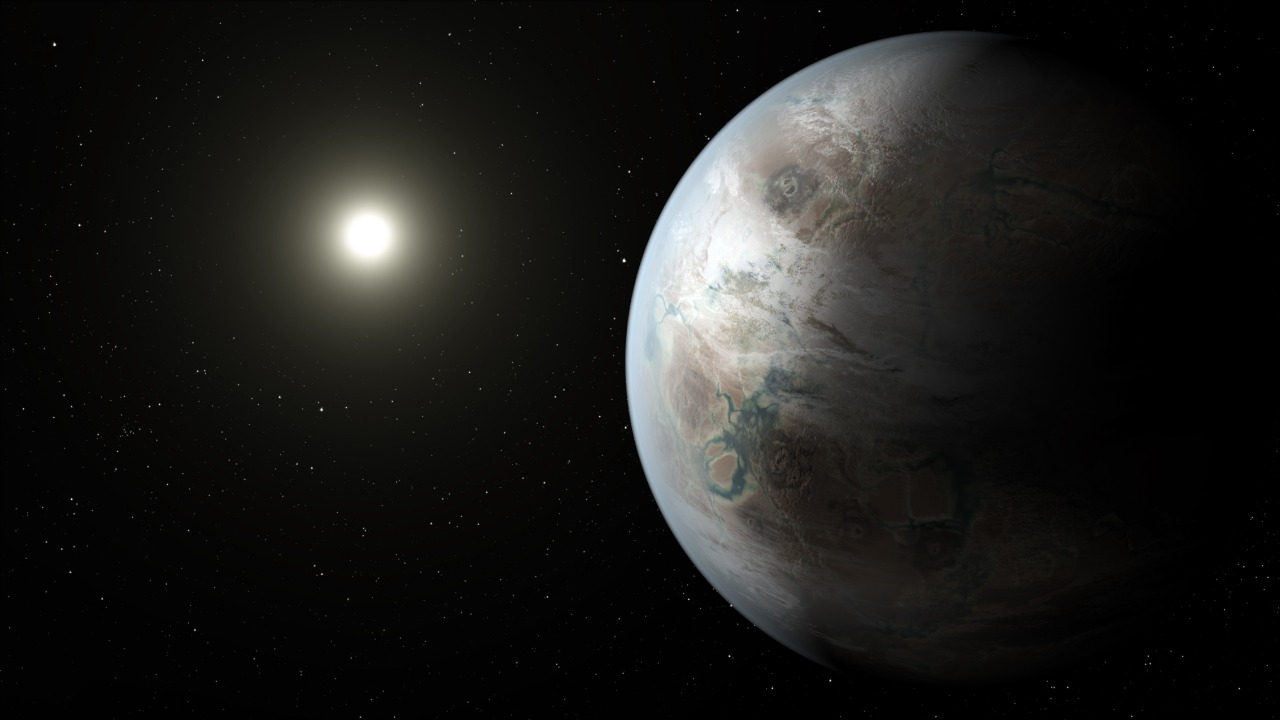

In more technical catalogs, Kepler-452b is placed about 1,800 light years away, or roughly 550 parsecs, in the constellation of Cygnus, a patch of sky that the Kepler spacecraft watched continuously. Models based on its size and orbit suggest a probable rocky composition and a surface that is a little warmer than Earth, which is exactly the kind of environment where geologic activity and long-lived oceans might be possible. An Artist’s impression of the planet shows a blue-green world under a slightly brighter star, a visual shorthand for how familiar and yet how alien this cousin really is.

From “Earth twin” headlines to sober comparisons

When the discovery was first unveiled, it was quickly framed as the “closest Earth twin yet,” a phrase that captured public imagination but glossed over important differences. Coverage of the Finds Closest Earth in a Haul of Alien Planets noted that the Kepler spacecraft had identified a batch of about 500 new candidates, but Kepler-452b stood out because its star is only slightly older and cooler than the Earth’s Sun. That framing helped convey why astronomers were excited, but it also risked implying that the planet is a near-perfect match, which the data do not support.

More recent analysis has leaned into nuance. A feature on how Kepler Several Exoplanets Are to Earth but There is Not an exact twin stresses that planets like Kepler-452b are invaluable precisely because they are similar but not identical. That difference lets scientists test how small shifts in mass, stellar brightness, or orbital distance might change climate and geology, which in turn shapes the odds that life can emerge and persist.

Could Kepler-452b actually host life?

Habitability is about more than distance from a star, and Kepler-452b sits at the center of an ongoing debate about what “Earth-like” really means. One detailed look at the system notes that the planet might be a kind of sub-Neptune, with a solid core wrapped in ice and a thick atmosphere, although the same report notes that it is more likely rocky according to NASA. That same analysis emphasizes that the system’s estimated age is significantly greater than that of the solar system, which means any potential biosphere would have had more time to evolve, but also more time to be stressed by a brightening star.

Earlier coverage framed the planet as a place that could plausibly support oceans and even active geology. One report described how the world, Called Kepler 452b, is a bit bigger than Earth and could have a surface suitable for water and life, and quoted scientists speculating about whether its interior might still host In the form of active volcanoes. Those volcanoes, if present, could recycle carbon and other gases into the atmosphere, stabilizing climate over billions of years, which is one of the key ingredients for long-term habitability.

Listening for a signal from Earth’s “older cousin”

The prospect that Kepler-452b might not just be habitable but inhabited has already prompted targeted searches for technology. Within days of the announcement, SETI astronomers began pointing radio telescopes at the system, treating it as a prime candidate in the Search for Extraterrestrial. Scientists at the Institute described Kepler-452b as Earth’s “older cousin” and used sensitive receivers to hunt for narrow-band radio signals that might betray artificial transmitters. So far, those searches have not turned up anything definitive, but the effort underscores how quickly a promising exoplanet can move from a statistical detection to a concrete target for technosignature surveys.

Ground-based astronomers are also working to refine what is known about the planet’s mass and atmosphere, which will shape future listening campaigns. In one interview, Mike Endl, a research scientist with University of Texas at Austin’s McDonald Observatory, told the Standard that Kepler-452b is one of the best examples of how the Kepler mission has revealed where those Earth-size planets are. That kind of ground truth is essential for deciding which worlds deserve the most telescope time when the next generation of observatories comes fully online.

More from Morning Overview