NASA’s Curiosity rover has photographed a knobbly Martian rock that looks strikingly like a piece of ocean coral, a reminder of how alien geology can mimic familiar Earth life. The tiny formation, nicknamed “Paposo,” is only about an inch across, yet it has reignited public fascination with the Red Planet’s watery past and the tools scientists use to decode it. I see this as one of those rare images that compresses a decade of Mars exploration into a single, uncanny frame.

Behind the viral resemblance is a serious scientific story about ancient groundwater, strange mineral growths and the slow sculpting power of Martian wind. The coral lookalike is not evidence of a Martian reef, but it is a product of the same basic ingredient that once sustained oceans on Earth: liquid water moving through rock.

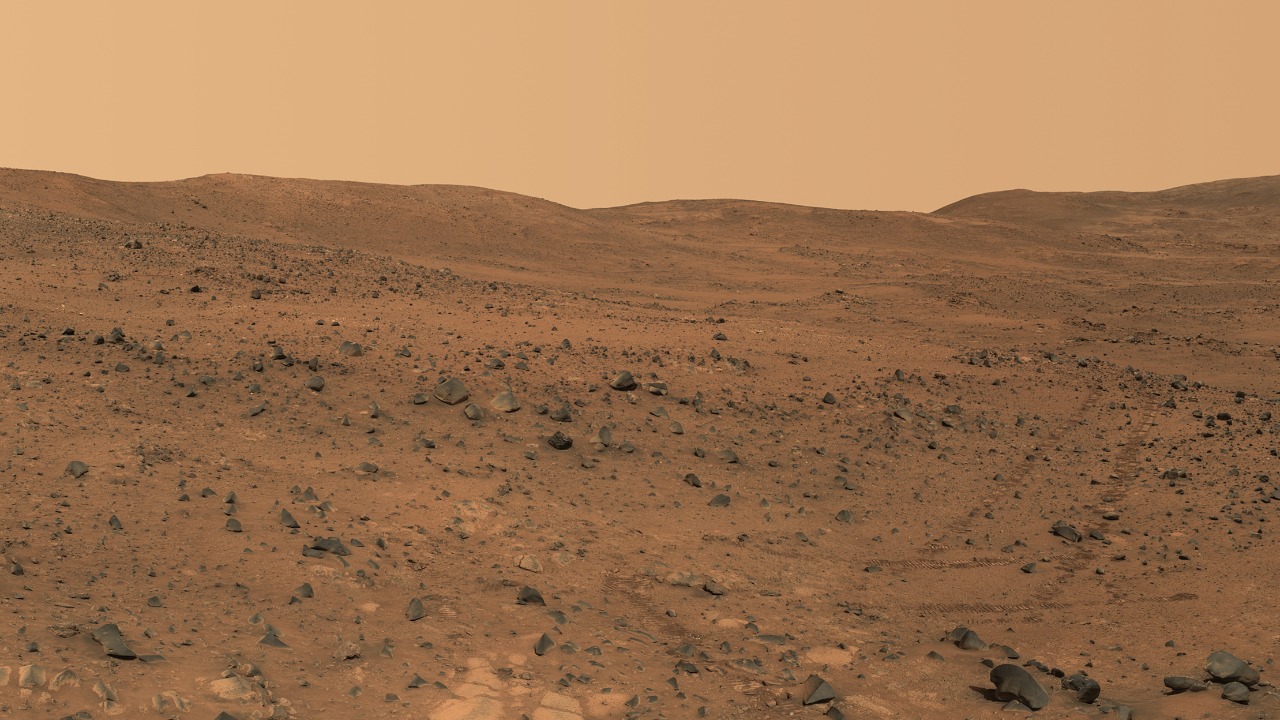

What Curiosity actually saw when it met “Paposo”

The coral shaped rock came into focus when NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover pointed its close up camera at a rough, branching lump on the ground in Gale Crater. Using the Mars Hand Lens Imager, or MAHLI, the rover captured a detailed view of the object that showed delicate protrusions and cavities, the kind of texture that immediately calls to mind a bleached coral fragment on a beach, and the image was later highlighted in an official Curiosity view. Mission scientists informally dubbed the rock “Paposo,” a nod to coastal landscapes on Earth that also mix wind, water and rock into intricate forms.

According to technical descriptions of the observation, the MAHLI instrument recorded the Paposo rock on July 24, 2025, at a distance of just a few centimeters, revealing that the entire structure is only about 1 inch across. That scale is crucial, because it shows how much fine detail Martian geology can pack into a very small volume when mineral veins, fractures and erosion all interact. A later analysis of the image notes that the Mars Hand Lens Imager is designed to act like a geologist’s magnifying glass on the surface, and that capability is what allowed Curiosity to turn a nondescript pebble into a global talking point about Mars and its past rock detail.

Why the “coral” look does not mean Martian reefs

At first glance, Paposo and similar formations really do resemble branching corals from shallow tropical seas, which is why images of the rock spread quickly across social media and space science communities. Commentaries on the find stress that the resemblance is visual, not biological, and that the structure is best explained as a mineral deposit that filled cracks in older rock before the surrounding material eroded away. In other words, the coral like shape is a geological cast, not a fossil, a point that has been emphasized in detailed breakdowns of these coral shaped rocks.

Researchers who follow Curiosity’s traverse have also pointed out that Mars has a long history of producing “pareidolia” moments, from face like mesas to animal shaped boulders, and that Paposo fits into that tradition of evocative but nonbiological forms. A closer look at the science behind the image, including the way MAHLI was used to document the rock’s texture and context, reinforces that the mission team is treating it as a clue to past water flow and mineral chemistry rather than as a direct sign of life. The same instrument description that highlights the Mars Hand Lens Imager’s role in capturing Paposo also situates it within the broader Curiosity Mars mission to read Gale Crater’s layered history.

How water and wind sculpted Paposo’s strange geometry

The leading explanation for Paposo’s branching form starts with water moving through fractures in ancient Martian bedrock, depositing minerals that hardened into resistant veins. Over immense spans of time, the surrounding softer rock was stripped away by erosion, leaving behind the tougher material in a three dimensional lattice that just happens to resemble coral. A detailed scientific note on the observation explains that on July 24, 2025, Curiosity’s MAHLI camera documented how these mineral veins intersect and protrude, and that the rock’s current shape likely reflects both the chemistry of the deposit and the way Martian winds have abraded the surface, a process summarized in a technical Paposo analysis.

Public facing explanations of the find echo that story, noting that the thin Martian atmosphere can still drive sand grains hard enough to sandblast rock and carve out intricate forms over time. One widely shared discussion of the image points out that the Red Planet’s winds often sculpt small rocks into bizarre, branching or hollowed shapes that invite comparison to familiar objects on Earth, including corals, sponges and even trees, and that Paposo is simply a particularly vivid example of this Martian wind sculpting. I see that dual role of water and wind as the key to understanding why such a small rock can carry such a big scientific message.

From Gale Crater’s boxwork to fast streams, Curiosity’s water story deepens

Paposo is not an isolated curiosity, it is part of a broader pattern of watery clues that Curiosity has been collecting in Gale Crater for more than a decade. Earlier in its current campaign, the rover entered a region marked by intricate “boxwork” formations, where mineral filled fractures form honeycomb like patterns in the rock, and mission updates describe how Curiosity drilled into this area to sample material that may record groundwater circulating through the subsurface billions of years ago. Those same updates note that the rover is now exploring a sulfate rich layer on the slopes of Mount Sharp, a zone that could reveal how changing water chemistry shaped the crater’s history, and they frame Paposo as one more expression of that complex groundwater story.

Looking back further, Curiosity’s record includes some of the earliest clear evidence that Mars once hosted flowing streams. Soon after landing, the rover imaged rounded pebbles embedded in bedrock, a texture that geologists interpreted as the product of a fast moving, possibly waist deep stream that tumbled stones along its channel until they were smoothed. Reports from that period describe how the shapes and sizes of the clasts matched what would be expected from water transported gravel on Earth, and how the discovery helped cement the idea that Gale Crater once held a lake fed by active Martian waterways. In that context, a coral like rock is less a surprise and more a natural outgrowth of a landscape that has been shaped by water in multiple phases.

Public fascination, viral images and what scientists say they mean

The Paposo image did not stay confined to technical mission logs. It quickly appeared in public posts that framed it as a “Strange Mars Discovery,” complete with side by side comparisons to ocean corals and reminders that the rock is only about 1 inch wide. One widely shared description emphasized that the picture was captured in late July by Curiosity and credited the image to NASA, JPL Caltech, MSSS, CNRS, IRAP, IAS and LPG, underscoring how many institutions contribute to a single Martian close up. I find that level of collaboration as striking as the rock itself, because it shows how international the hunt for Mars’ secrets has become.

News outlets and broadcasters also picked up the story, often highlighting that NASA’s Curiosity rover had spotted unusually shaped rocks on Mars’ surface and that the team had nicknamed the standout example “Paposo.” One broadcast summary described how the rover’s cameras revealed multiple coral like forms in the same area, suggesting that the processes that created Paposo may be operating across a broader patch of Gale Crater, and it stressed that the rover responsible is the same NASA Curiosity that has been exploring Mars since 2012. That continuity matters, because it means scientists can place each new oddity into a long running narrative of the crater’s evolution.

More from Morning Overview