Most people are convinced they see the world exactly as it is, until a viral illusion quietly proves otherwise. The latest circle-filled puzzle racing around social feeds is a reminder that even confident adults can stare straight at a simple pattern and miss what is right in front of them. The failure is not about intelligence, it is about how the brain edits reality before we ever become aware of it.

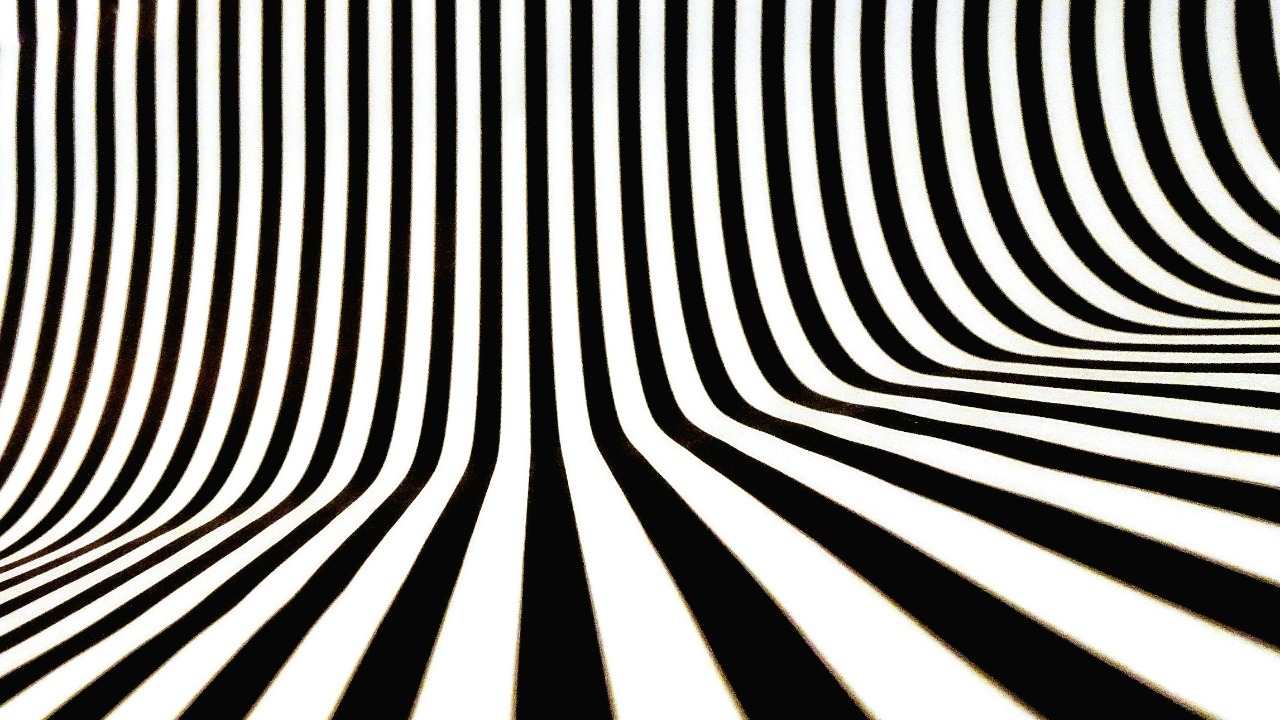

The illusion at the center of the current craze looks like a grid of narrow rectangles, yet it secretly hides a ring of perfect circles. Viewers argue in the comments about what is really there, certain they are right, while the image calmly exposes how perception is built from shortcuts, expectations and a lifetime of visual habits.

Why your brain refuses to see the circles

The viral test that most adults are flunking is a modern spin on a classic known as The Coffer Illusion, a pattern that seems to show a grid of panels but actually contains sixteen circles. In the newer version, people initially report only a wall of vertical and horizontal bars, because the visual system is primed to detect straight edges and rectangles that resemble doors or windows. Only after someone points it out, or after a long stare, do the hidden curves suddenly snap into focus and the circles appear to “pop” out of the pattern.

One practical trick that helps is to stop looking at the shapes themselves and instead pay attention to the gaps between them. Focusing on the vertical bars between the rectangles can make the circles abruptly emerge, a perceptual flip that feels almost like a magic reveal and has been highlighted in guides that walk viewers through One specific way to unlock the pattern. The fact that so many adults need coaching to see something as basic as a circle shows how strongly the brain favors familiar structures, even when they are not really there.

The viral “only 1%” challenges and what they really measure

Once you start noticing these perception gaps, social media is full of tests that promise to sort the sharp-eyed from the rest. Timed puzzles invite users to find a single odd symbol in a dense field of lookalikes, with captions insisting that Viral Optical Illusion fans can spot the “odd one out” in 7 Seconds and that Only 1% succeed. These games rely on the same mechanisms as the circle grid: the eye skims for patterns, the brain fills in regularities, and tiny deviations vanish unless attention is precisely targeted.

Number-based riddles push the same buttons, asking people to locate a flipped pair of digits in a sea of nearly identical numbers. One popular Puzzles and IQ invites readers to find an inverted 94 in under seven seconds, framing it as a measure of “visual perception and recognition skills” and bundling it under Quick Links for brain teasers. In practice, these challenges are less about raw intelligence and more about how efficiently someone can override their brain’s urge to generalize, a skill that can be trained but that also varies from person to person.

Illusions that reach into your body, not just your eyes

Some illusions do more than trick awareness, they provoke measurable physical reactions. Psychologists at the University of Oslo in Norway reported in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience that a static pattern of a dark disk, nicknamed the “expanding hole,” makes viewers feel as if they are moving into a tunnel. Around 80 percent of people see the central region swell toward them, while the rest perceive only a flat image, and no one is yet sure why the population splits so sharply.

Follow-up work on the same illusory pattern has shown that the effect is not just in the mind. The circular smear or shadow gradient at the center mimics the cues of a real dark hole, and the pupil responds as if light were actually changing, dilating in anticipation of entering a darker space. Coverage of the research notes that Although the image is completely static, the pupils expand even when the viewer is fully aware that nothing is moving. Social posts summarizing the findings emphasize that However, around 20 percent of people do not see the expanding effect at all, hinting at deep individual differences in how visual cues link to unconscious bodily responses.

Scientists who study this phenomenon argue that the same thing might be happening in other illusions that simulate motion or depth. One analysis notes that “The same thing might be happening here,” suggesting that those who do not feel as if they are entering a tunnel are making a more accurate judgment about the flatness of the image, while the rest of us are fooled by its visual trickery, a point explored in detail in illusion coverage. The expanding-hole studies show that a viral picture on your phone can quietly tug on the same reflexes that help you navigate a dark hallway, even as you sit still on the couch.

When illusions pretend to read your personality or your future

Alongside the perception tests, a different genre of viral image promises to decode who you are, or even what the next year will bring, based on what you notice first. One widely shared picture of overlapping creatures claims to reveal your traits depending on which animal pops out at a glance, a format unpacked in detail by a Jan explainer. The analysis points out that this overlapping-animals illusion leans on fast, automatic categorizing and that Whatever “pops out” first is not a magic label for your soul, it is a reflection of which shapes your brain is quickest to assemble.

Another trending picture packs multiple animals into a single frame and claims to show what 2026 holds based on the creature you notice first. Reports describe how a viral optical illusion featuring multiple animals assigns different meanings depending on which figure you spot first in the image, suggesting that a single picture could potentially hint at what your 2026 might signify. Psychologists have long warned against reading too much into such claims, and research on the Silhouette Illusion shows why: a psychology professor found that the way people perceive that spinning figure, which went viral in personality quizzes, does not reliably map onto the left-brain or right-brain attributes those quizzes claimed to diagnose.

The Coke can that is not red and the circles that never show up

Color illusions add another twist, revealing how much the brain relies on context and memory rather than raw wavelengths. In one experiment shared by researchers at UC Berkeley, viewers are shown what looks like a bright red soft drink can, yet the image contains no red pixels at all. A post from the university describes how, at first glance, you would swear you are looking at a bright red Coca Cola can, but the stripes are carefully tuned so that the mind automatically “corrects” the colors. A separate viral photo of a Coke can, shared by a creator who urges viewers to “Zoom in and find out,” uses only white, blue and black tones, yet Yet the brain fills in the expected red because it recognizes the brand.

Artists have leaned into this effect on platforms like Instagram, where one creator posts, “Check this out!!” alongside a striped soft drink image that has been surprising people because their minds automatically correct the image, a reaction also highlighted in a related Jul post. The same stubbornness shows up again in the circle illusion: detailed breakdowns of The Coffer Illusion explain that it features a pattern of black, white and gray lines that appear to form rectangles, and that the true challenge is to spot the sixteen circles hidden inside shapes that are more common in our environment. Coverage of the same image notes that Now, almost two decades after it was created, The Coffer illusion is still leaving people perplexed and that Most viewers see only the squares or “coffers” as they struggle to find the circles.

More from Morning Overview