SpaceX’s lunar Starship was never designed to blaze back through Earth’s atmosphere in a shower of plasma. Instead, the company has quietly positioned its Human Landing System as a one‑way ferry that lives and dies in cislunar space, while NASA’s Orion capsule handles the brutal trip home. That architectural choice, long embedded in Artemis planning documents, is only now breaking through to a wider public that assumed every Starship would eventually come back to Earth.

Framed correctly, this is less a retreat from reusability than a bet on specialization. By stripping out the heavy heat shield and recovery hardware, SpaceX can turn its lunar variant into a tall, fuel‑hungry elevator between orbit and the Moon, while the rest of the Artemis stack focuses on launch and reentry. The tradeoffs behind that decision reveal how NASA and SpaceX are trying to thread the needle between ambition, schedule pressure, and basic physics.

Artemis needs a lunar shuttle, not a return capsule

NASA’s Artemis architecture was built around the idea that no single vehicle would do everything, and that includes the trip home. The agency’s own outline for Artemis III makes clear that astronauts will launch on the Space Launch System, ride in Orion to lunar orbit, then transfer into a separate lander for the descent and ascent. The Artemis program description spells out that SLS and Orion are the pieces designed for deep‑space transit and Earth reentry, while the lander is a dedicated vehicle for the last leg between orbit and the Moon’s surface.

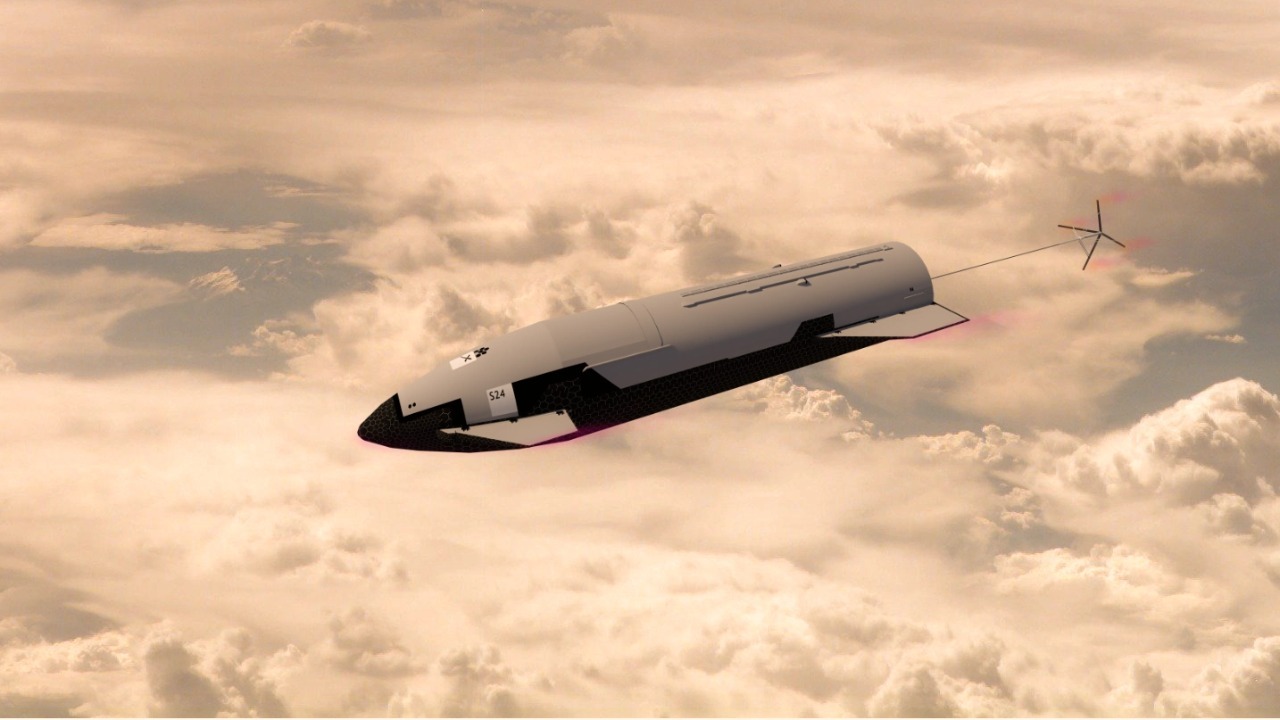

That division of labor is why NASA refers to SpaceX’s vehicle as the Starship Human Landing System, or HLS, rather than simply Starship. Agency material on the Initial Human Landing concepts shows a tall, stripped‑down lander on the Moon, with Orion waiting in lunar orbit as the ride home. In other words, the mission design assumes from the start that the lunar Starship is a shuttle between the Moon and orbit, not a capsule that ever sees Earth’s atmosphere.

Inside the one‑way Starship design

SpaceX’s own technical descriptions underline that the lunar lander is a specialized branch of the broader Starship family. A detailed overview of Starship‑HLS notes that the Human Landing System is derived from Starship but modified for operation as a lunar lander, and explicitly states that this configuration is not designed to return to Earth. That is not a late‑breaking compromise, it is a core assumption baked into the hardware, from the missing heat shield to the absence of aerodynamic control surfaces needed for atmospheric entry.

The logic behind that choice has even filtered into public discussion among enthusiasts and engineers. In one widely shared explanation, Forrest and Townsend tell fellow fans that engineers “dont’ plan on ont he lunar starship to return to earth, no heatshield, save on the cerami,” while David Cluett promises to explain the trade in layman’s terms. The point is simple: every kilogram not spent on ceramic tiles and reentry systems can be spent on propellant, cargo, or life support for the lunar mission itself.

Why Orion still matters in a Starship era

The decision to keep the lunar Starship in space also explains why Orion remains central to NASA’s plans, despite Starship’s headline‑grabbing capabilities. A technical discussion of whether the lander could replace Orion, framed as Can Starship Lunar return to Earth orbit so Orion is not needed anymore, points back to the reality that Orion on SLS is planned to handle the high‑energy return and splashdown. The Orion capsule is built around a robust heat shield and abort systems that the lunar Starship variant simply does not carry.

Programmatically, that means Artemis is locked into a choreography where SLS, Orion, and the lander are all indispensable. The SLS missions listed for Artemis I, Artemis II, and beyond show a steady cadence of Orion flights, while separate documentation describes how the Starship Human Landing will be instrumental in ferrying crews from lunar orbit to the surface and back. That is why, even in a Starship era, Orion’s role as the Earth‑return vehicle is not a redundancy but a structural pillar of the mission design.

A “simplified” mission profile, still complex in practice

As schedule pressure mounts, SpaceX has been working with NASA on what it calls a simplified mission architecture for the lunar lander, but that streamlining does not include bringing the vehicle home. Company representatives have described to NASA a Starship for NASA approach that reduces the number of on‑orbit refueling events and mission steps while still delivering astronauts to the lunar surface. A separate account of that simplified approach notes that the company is defending the viability of its lander even as it trims complexity to hit key milestones.

Critics inside the space community have questioned whether those changes are enough. At a high‑profile event, former NASA leaders Charlie Bolden and Jim Bridenstine expressed skepticism that the current Starship schedule could deliver on time, even with a leaner mission design. Yet SpaceX has publicly stood behind its timeline, with one detailed feature on its lunar plans, titled around Fly Me to the Moon, stressing that, unlike Apollo, Unlike Apollo, Artemis III will rely on a multi‑vehicle choreography that includes several crucial milestones in 2025.

Refueling, timelines, and the politics of delay

Behind the scenes, the biggest technical swing remains in‑space refueling, which is essential if a non‑returning lander is going to haul enough propellant to and from the Moon. SpaceX’s official updates describe how the next major flight milestones tied specifically to HLS will be a long‑duration flight test and an in‑space propellant transfer in Earth orbit. Without those capabilities, the one‑way lunar Starship would struggle to carry the fuel it needs for multiple sorties between lunar orbit and the surface.

That technical risk feeds directly into political anxiety. In one public exchange, Rob Jacobs But the points out that the many Falcon 9 flights are irrelevant to NASA’s immediate problem, because what the agency needs is HLS, which is a special version of Starship. That concern has grown loud enough that NASA has signaled it may consider new proposals from other top space companies to get America back to the Moon if delays mount, a reminder that the lunar Starship’s one‑way design does not insulate it from competition.

More from Morning Overview