Physicists are no longer content to let atoms blur into invisibility. By squeezing light into pulses that last just billionths of a billionth of a second and pairing them with cameras that tick at trillions of frames per second, they have effectively smashed light’s own practical speed limit, slowing its motion by factors of 100,000 and more. I see that shift not as a stunt, but as the moment when the quantum world starts to look less like theory and more like something you can literally watch unfold.

The race to capture atoms in action has produced record breaking light bursts, ultrafast X‑ray lasers, and imaging systems that can follow photons as if they were drifting snowflakes. Together, these tools are turning the once abstract realm of electrons and chemical bonds into a filmable landscape, with implications for electronics, clean energy, and even brain science.

From everyday shutters to attoseconds

To understand how radical this is, I start with something familiar. On a bright day, a typical camera might open its shutter for a few thousandths of a second to photograph a moving crowd, a span that already feels instantaneous to us. Experimental “atom snapping” systems now cut that window down to about 1/1000000000000th of a second, as demonstrated in an Oct project that shows how far conventional intuition has to stretch once you leave human timescales behind.

Even that trillionth of a second is leisurely compared with the frontier of attoscience. An attosecond, defined in the International System of, is 10⁻¹⁸ seconds, or one quintillionth of a second, a scale so small that light itself barely travels the width of a few atoms in that time. The same definition appears in a dedicated attosecond entry, underscoring how this unit has become a standard yardstick for probing electron motion rather than an exotic curiosity.

Building the shortest light pulses in history

The key to freezing atomic motion is not just fast cameras, it is sculpted light. Over the past year, teams working in attoscience have carved laser bursts into what they describe as the shortest light pulse ever created, compressing energy into a spike that lasts only a few tens of attoseconds. One group reported that this record pulse emerged from a carefully tuned sequence of nonlinear optics and laser engineering, a feat detailed in a Dec announcement that framed the result as a new barrier broken.

A complementary report on a Record breaking pulse highlights how advances in laser engineering and attosecond metrology are converging. In parallel, a separate Related note points to “Chiral” thermal emission and “Quantum” imaging as part of the same ecosystem of techniques, all aimed at controlling light with such precision that it can interrogate matter on its own natural timescale.

Atomic X‑ray lasers and the 60–100 attosecond window

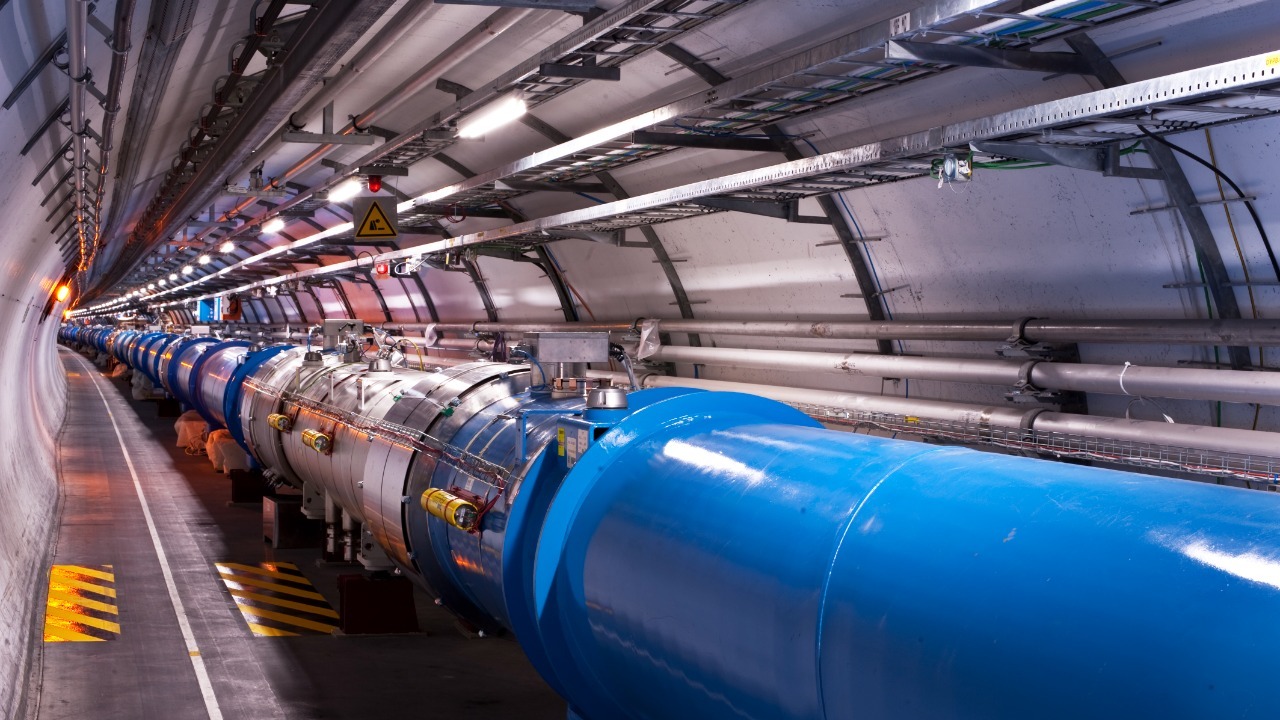

Visible and infrared pulses are only part of the story. To see deep into atoms, researchers have pushed into the X‑ray regime, where photons carry enough energy to interact directly with core electrons. In work highlighted by Scientists at a major accelerator lab, teams created the first attosecond atomic X‑ray laser, turning a particle facility into a strobe light for electrons.

Those X‑ray flashes, according to Researchers, enabled a measurement of an “ultrafast chorus dance” of electrons on a super small particle, the first time such collective motion has been tracked directly. A separate explainer on what happens when scientists push light to its absolute limit notes that these high energy X‑ray bursts can last only 60 to 100 attoseconds, a range spelled out in a Jun video that emphasizes how extreme that compression really is.

Cameras that slow light to a crawl

Light pulses alone are not enough, you also need detectors that can keep up. Earlier work at Caltech produced an ultrafast camera that can record transparent phenomena at 1 trillion frames per second, a benchmark described in a Caltech release that showed laser pulses crawling across a scene in slow motion. That system built on an earlier generation of high speed imaging, including setups that, as Thomas Murphy noted for The Science of Things, could manage 10,000,000,000 frames per second and were already described as Public demonstrations of Capturing light in flight.

More recently, an imaging platform described as a “Trillionth of a Second Camera Captures Chaos in Motion” has been used to study dynamic disorder in materials, with Trillionth scale exposures revealing how atoms jiggle and rearrange in real time. A separate Sep demonstration from MIT shows a camera so fast it slows the fastest moving thing in the universe, light, to a crawl, underscoring how imaging has caught up with the pulses that drive attoscience.

70 trillion frames per second and the road to applications

The most aggressive leap in this race comes from a system that takes 70 trillion pictures per second, a rate that effectively stretches a femtosecond event into a sequence of discrete frames. In technical terms, the optics break up individual femtosecond pulses of laser light into a train of even shorter pulses, with each of those pulses captured as a separate frame, a design described in detail in a New ultrafast camera report. A companion link to the same work notes that this approach emerged from collaborations that include the Tianqiao and Chrissy Chen Institute for Neuroscience at Caltech, hinting at crossovers between photonics and brain research in a second Institute focused description.

Scientists at Caltech have framed these cameras as tools for more than just pretty videos. In a widely shared note, Scientists at Caltech describe the fastest camera they have engineered as capable of recording light itself as it moves, with potential for diagnosing faults in high speed electronics, improving optical communication systems, and advancing materials science. A related Public post by Thomas Murphy for The Science of Things emphasizes that Capturing such events at 10,000,000,000 frames per second was once headline worthy on its own, which puts the 70 trillion benchmark into perspective.

More from Morning Overview