The National Aero-Space Plane was sold to the public as a kind of orbital bullet train, a sleek “Orient Express” that could sprint from Washington to Tokyo in a couple of hours and then keep going all the way to orbit. In the late Reagan years it was pitched as a revolution in both air travel and space access, a single vehicle that could take off from a runway, accelerate to roughly Mach 25, and glide back to Earth like an airliner. Instead it became a case study in how political ambition, immature technology, and shifting priorities can doom even the most intoxicating aerospace dream.

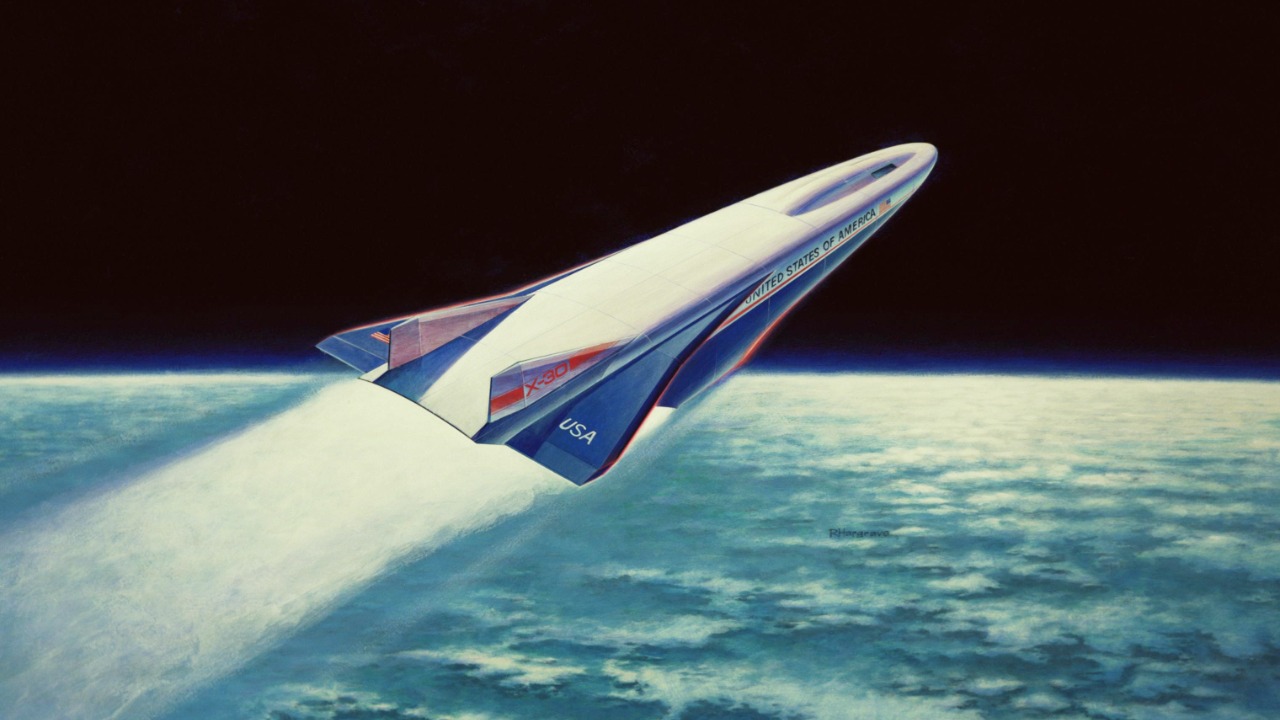

At the center of that dream sat the Rockwell X-30, the experimental craft meant to embody the National Aero-Space Plane, or NASP, and turn presidential rhetoric into metal. The X-30 never flew, and not even a full-scale prototype was completed, but the program left behind a paper trail, wind-tunnel models, and a surprisingly durable cultural footprint that still shapes how engineers and policymakers talk about hypersonic flight today.

Reagan’s “Orient Express” promise and the birth of NASP

When Ronald Reagan talked about an “Orient Express” spaceplane, he was not just indulging in science fiction, he was putting presidential weight behind a specific technical vision: a craft that could leave a conventional runway, accelerate through hypersonic speeds, and reach orbit without staging. That vision coalesced into the National Aero-Space Plane, or NASP, a program that aimed to leapfrog traditional rockets by using the atmosphere itself as propellant. The goal was not modest: a reusable vehicle that could hit orbital velocity, roughly Mach 25, and then land back on a runway, turning spaceflight into something that looked and felt like long-haul aviation.

To turn that rhetoric into hardware, the government tapped Rockwell to lead development of the X-30, the sleek demonstrator that would prove the NASP concept in flight. The Rockwell design was meant to be a single-stage-to-orbit craft, blending advanced materials, integrated fuel tanks, and a complex airframe that doubled as an engine duct. It was a bold attempt to compress decades of incremental progress into one flagship project, and from the start, the gap between the political promise and the technical reality was already widening.

The X-30: a hypersonic spacecraft on paper

On paper, the X-30 was a one-vehicle revolution, a craft that would behave like an aircraft at takeoff and landing but like a spacecraft at peak speed. The design called for a lifting body fuselage, a sharply swept nose, and a blended wing that would generate lift while also housing fuel and structural supports for the engines. The NASP concept envisioned the X-30 as a reusable orbital vehicle, and artist impressions showed the X-30 entering orbit with a glowing shock layer wrapped around its nose and leading edges. The vehicle was supposed to carry a small crew and payload, serving as both a testbed and a prototype for future operational spaceplanes.

Even at the mockup stage, the X-30’s ambitions were clear. A one-third scale model was built as a hypersonic spacecraft demonstrator, with engineering students from Missi working on a configuration sized for a crew of two. That Missi mockup captured the cramped, high-performance interior that a real NASP vehicle would have required, with every cubic centimeter of volume contested by life support, avionics, and structural reinforcement. It was a reminder that the X-30 was not just a sleek exterior, it was a systems engineering nightmare that had to reconcile orbital speeds with human occupants.

Scramjets, “Performance” creep, and impossible physics

The technical heart of the NASP dream was the scramjet, a supersonic combustion ramjet that would gulp in air at hypersonic speeds and burn hydrogen fuel inside a supersonic airflow. By the early 1980s, some researchers argued that scramjet technology was ready to power an aircraft, but that optimism proved fragile once engineers started adding real-world constraints. As design studies matured, By the time the X-30 concept solidified, weight, complexity, and cost had all climbed, while the projected performance steadily eroded. The elegant idea of a single engine system that could operate from takeoff to orbit gave way to a patchwork of modes and compromises that strained credibility.

Inside the program, the goals themselves became part of the problem. As requirements accumulated, the official Performance targets increased, creating a widening mismatch between what engineers could realistically deliver and what policymakers expected. The workload ballooned, and the program began to echo earlier cautionary tales in which rising ambitions, fixed budgets, and schedule pressure combined to compromise safety and feasibility. In NASP’s case, the result was not a catastrophic accident but a slow recognition that the physics and materials of the era could not support the promised Mach 25 spaceplane.

Inside the cabin: designing for Mach 25 humans

Even if the X-30’s engines and structure had worked as advertised, the human factors challenges were daunting. A vehicle that could accelerate from subsonic speeds to orbital velocity in a single continuous climb would subject its crew to prolonged high-G loads, intense vibration, and extreme thermal gradients. Cabin designers had to imagine seats and restraints that could keep astronauts functional through that profile, while still allowing them to operate controls and survive an emergency landing. In one study of a related spaceplane interior, engineers concluded that, Instead of copying existing spacecraft couches or airline seats, a synthesis of historical spacecraft seating and contemporary office seating offered the best compromise between support and mobility.

That conclusion, detailed in a case study of the XP spaceplane, underscored how much of NASP’s challenge lived inside the cockpit rather than on the outer mold line. The Instead approach to seating design tried to balance ergonomic comfort with the need to withstand high accelerations and rapid attitude changes. It is a reminder that a Mach 25 vehicle is not just a propulsion problem, it is a human survivability problem, one that has grim real-world analogues. When Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, a Boeing 737 Max, crashed at 575 mph, investigators reported that the plane’s speed exceeded its design limits and that passengers would have experienced negative G-forces before impact, a brutal illustration of what happens when human bodies are pushed beyond what an airframe is built to handle, as detailed in a Reuters-based account.

Politics, hype, and the slow death of the X-30

Behind the engineering drama, NASP was also a political project, born in the late Cold War and wrapped in the language of national prestige. Earlier studies of an Aerospaceplane had already explored similar ideas, and an artist’s impression of such a vehicle in flight, shared as an IMG under a Wikipedia license, captured the futuristic aura that surrounded the concept. Related work on high-speed air-breathing propulsion and advanced materials fed into NASP, but the program’s visibility also made it vulnerable to shifting administrations and budget priorities. As costs rose and timelines slipped, the X-30 became an easy target for critics who saw it as a technological overreach.

Inside the program, multiple government agencies and contractors had to coordinate on a baseline design that could satisfy both military and civilian ambitions. A documentary on National Aerospace Plane describes how engineers from five government agencies joined forces around a baseline configuration initially developed by millionaire Tony Dupont, a reminder that private visionaries and public institutions were deeply intertwined in NASP’s genesis. That Tony Dupont baseline had to be reshaped repeatedly as technical realities intruded, and each redesign chipped away at the original promise of a sleek, passenger-ready Orient Express to orbit.

More from Morning Overview