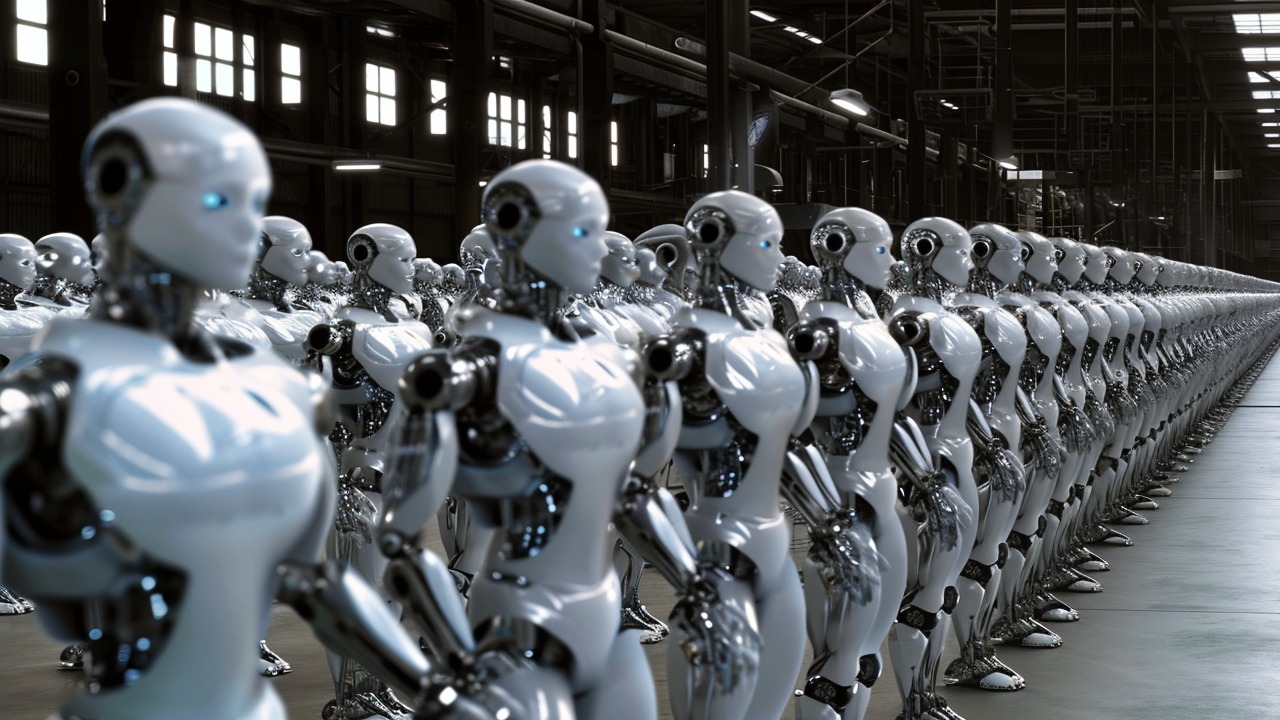

Humanoid robots are no longer a distant sci‑fi promise. They are quietly stepping into warehouses, hospitals, and even homes, helped by rapid advances in artificial intelligence and falling hardware costs. The shift is happening so quickly that regulators, workers, and consumers are scrambling to catch up with machines that look and move like us, and increasingly, work alongside us.

What once sounded like hype is now a visible market, from industrial pilots to consumer gadgets that can be ordered online. As I trace the latest deployments and investment flows, it is clear that humanoids are entering daily life far sooner than most policymakers or the public expected, and the choices made in the next few years will shape how comfortably we live with them.

The leap from lab demos to real-world autonomy

The most important change in humanoid robotics is not the hardware, it is the software that lets these machines perceive, decide, and act without constant human teleoperation. In one widely cited example, a robot in 2024 saw its surroundings, chose a course of action, and executed it on its own, a moment that signaled how far embodied AI had come from scripted routines. That kind of autonomy, described in detail by Aug, is what turns a humanoid from a showpiece into a worker that can handle messy, unpredictable environments.

Yet even as perception and decision‑making improve, the same analysis stresses that serious obstacles still block the path to fully reliable, general‑purpose humanoids. Power density, safety, and robustness remain limiting factors, and the most advanced systems still struggle with long shifts, slippery floors, or crowded spaces. I see this as a classic technology crossing the gap between prototype and product: the breakthrough is real, but the edge cases are where lives and reputations are on the line, which is why researchers and companies are moving cautiously even as they celebrate autonomy milestones.

From factory pilots to mass deployment

Behind the scenes, manufacturers are already planning for a world where humanoids are as common on factory floors as forklifts. Industry forecasts cited by Aug point to a near‑term outlook in which hundreds of thousands of humanoid robots are deployed in industrial settings, with a market that could reach 38 billion by 2030–2035. That scale only makes sense if robots are not just novelties but integrated into production lines, logistics hubs, and maintenance operations where their humanlike form factor lets them use existing tools and infrastructure.

On the ground, early adopters are already experimenting with humanoids for repetitive and hazardous tasks, from pallet handling to inspection in confined spaces. A detailed look at industrial use cases notes that in manufacturing settings, humanoid robots are increasingly tasked with handling repetitive and hazardous work, freeing human staff for supervision and complex problem solving, a trend captured in the Key Takeaways on applications. I read this as the beginning of a division of labor where humanoids become the flexible, all‑purpose machines that can be dropped into legacy facilities without expensive retrofits.

Humanoids you can actually buy

For consumers and small businesses, the most striking change is that humanoid robots are now products with price tags, spec sheets, and delivery dates, not just research projects. A detailed buyer’s guide titled The Most Advanced Humanoid Robot You Can Buy Right Now describes machines that are powerful and ready to work, marketed as off‑the‑shelf helpers rather than experimental platforms. These systems promise out‑of‑the‑box capabilities like object manipulation, basic navigation, and voice interaction, aimed at offices, retail spaces, and affluent households.

Alongside that flagship tier, a broader survey of The Best Humanoid Robots Available in 2025 frames humanoids as indispensable tools that have transitioned from futuristic fantasies to practical assets. The same overview argues that these Humanoid systems are already delivering benefits in the years ahead, from customer service to education and entertainment. When I look at these catalog‑style listings, I see the early stages of a consumer market that will likely mirror the smartphone era: a few premium models, a long tail of niche devices, and a rapid cycle of upgrades that normalizes the idea of a robot as a household appliance.

China’s strategic humanoid push

While the United States hosts many of the best‑known robotics brands, China is moving aggressively to dominate humanoid manufacturing and deployment. One analysis notes that Elon Musk envisions humanoid robots everywhere, but that China may be the first to make it a reality, treating humanoid robots in 2025 as part of its broader strategic goals. That framing matters, because it places humanoids alongside electric vehicles and solar panels as sectors where Beijing wants to build global industrial leadership, not just domestic convenience.

Reporting on Chinese robotics firms shows how quickly that ambition is turning into hardware. One major company has various robotics models, including humanoids, and this year it debuted its latest model, the H2, showcasing it at a high‑profile tech event in Lisbon, while UBTech Robotics is highlighted as another key player that presented its humanoid systems in Germany, details captured in a recent Dec report. Another deep dive into the Chinese market argues that as breakthroughs in EAI, servomechanisms, and perception systems continue to accelerate, commercialization of humanoid robots is spreading across manufacturing, healthcare, logistics, and service sectors, a trend mapped in detail by EAI. I see this as a geopolitical race where supply chains, standards, and export policies for humanoids could become as contested as those for advanced chips.

From factories to homes and hospitals

The most visible frontier for humanoids is still industrial, but the line between factory and everyday life is blurring fast. A detailed preview of near‑term deployments notes that humanoid robots will march into factories and homes in 2025, with the US‑Norwegian company 1X, another robotics start‑up backed by OpenAI, preparing systems that could appear in ordinary homes as robot helpers, a scenario described in a Dec news preview. That same reporting stresses that Even ordinary homes could see robot helpers, not just luxury showrooms or tech labs, which is a crucial psychological shift.

Healthcare is another sector where humanoids are moving from pilot to practice. A comprehensive review of applications explains that Humanoid robots are transforming healthcare through tasks such as surgical assistance, elderly care, and rehabilitation, and that in industrial and manufacturing settings they are already handling repetitive and hazardous tasks, as outlined in the Humanoid applications guide. When I connect these dots, I see a pattern: the same core platforms that lift boxes in a warehouse are being adapted to lift patients in a clinic or assist an older person at home, which raises both exciting possibilities and hard questions about safety, liability, and human contact.

Everyday utility, but autonomy still lags

For all the hype, many experts caution that fully independent humanoids are still some years away. In a widely shared segment on DW News, researcher Alen Albuffller argues that it will be a number of years before humanoids are able to act autonomously in the way laypeople imagine, walking into a home or office and handling any task without supervision. That assessment matches what I hear from engineers who say that while robots can perform impressive demos, turning those into reliable, 24/7 services in cluttered human spaces is a much harder problem.

Yet even with those limits, humanoid robots already show utility for everyday tasks, from carrying items and opening doors to basic cleaning and delivery. A short Instagram reel from BostonDynamics B, tagged with Humanoid, captures experts saying that humanoid robots are moving from sci‑fi to reality way faster than expected, using hashtags like #AIAndRobots, #FutureOfWork, #RoboticsInnovation, and #Next10Years. I read that mix of caution and excitement as a sign that the field is in a transitional phase: robots are good enough to be useful, but not yet good enough to be invisible, which means humans will be adapting to their quirks for some time.

Economic stakes and the affordability problem

Behind the glossy demos lies a hard economic question: who can actually afford these machines, and at what scale do they make financial sense. A major analysis of AI and robotics warns that Even if performance improves, affordability may be difficult to achieve, because per‑unit costs of advanced, safe models would need to fall dramatically before they can be deployed widely, especially in low‑margin sectors, a point laid out in detail in a Nov research report. That same work notes that humanoids are particularly attractive for inspections of dangerous environments, where the cost of failure is high and the willingness to pay is greater, which is why early deployments cluster in oil, gas, and heavy industry.

Investors, however, are betting that costs will fall as volumes rise. In a televised discussion titled AI and humanoid robots surge in 2025: Industry sees explosive growth ahead, Moonfire Ventures founder Mattias Ljungman argues that the Industry is on the cusp of a major expansion, with capital flowing into companies that can scale production and integrate AI more tightly into hardware. I see a tension here: the business case for humanoids is strongest in high‑risk, high‑value niches, but the venture narrative depends on mass adoption, which may take longer than investors hope if affordability lags behind technical capability.

Demographics, care work, and the “new smartphones” analogy

One of the most powerful drivers behind humanoid adoption is demographic pressure, especially aging populations. A detailed analysis of care challenges notes that Globally, the issue will only intensify as populations age, and that The UN expects the number of people aged 65 and older to multiply in the coming decades, creating a gap between care needs and available workers, a trend laid out starkly in a Nov report. That same piece argues that humanoid robots are about to become the new smartphones of our lives, a metaphor that captures both their potential ubiquity and the way they might become personal, always‑on companions.

I find that analogy compelling but also unsettling. Smartphones reshaped attention and privacy in ways few anticipated, and humanoids could do the same for physical space and labor. If robots become as common as phones, they will not just assist with tasks but also collect data, mediate relationships, and potentially substitute for human contact, especially in elder care. The demographic imperative is real, and societies that cannot recruit enough caregivers will need to find them soon, but the choice to fill that gap with machines rather than migration or better pay for human workers is a political one as much as a technological inevitability.

Global race and the next decade of work

As humanoids spread, they are reshaping expectations about how humans, AI agents, and robots will share work. A major global forum on technology argues that At the same time, advances in AI technology have pushed humanoid robots from research labs into the marketplace, sparking both disruption and promise, with expanding applications driving market growth in sectors from logistics to hospitality, a dynamic described in a At the analysis. That framing captures the dual reality I see: humanoids can fill dangerous or undesirable roles, but they also raise fears about job displacement and the devaluation of certain kinds of physical work.

Public perception is evolving quickly. A short social clip tagged with #FutureOfWork and #Next10Years captures experts saying that humanoid robots are moving from sci‑fi to reality way faster than expected, and that the next decade will be defined by how workplaces integrate them. In parallel, a detailed feature on deployment patterns notes that the demand for mass production is closely linked to application deployment, and that humanoid robots are beginning to find applications more in industrial scenarios than home or commercial ones, a trend mapped in an Apr report. I expect that balance to shift as costs fall and software matures, but for now, the factory and the warehouse remain the proving grounds for the humanoid future.

The first wave of consumer humanoids

Even before humanoids become as ubiquitous as smartphones, a first wave of consumer‑facing robots is testing how people react to humanlike machines in their personal space. Online marketplaces already list humanoid products that can be ordered with a few clicks, complete with glossy photos and feature lists, as a quick search for a flagship product makes clear. These early models are often marketed as educational companions, security patrols, or novelty assistants, but they are also a live experiment in social acceptance, testing how comfortable families are with a robot that looks back at them.

Industry insiders are already debating which design choices will make humanoids feel trustworthy rather than uncanny. Some argue for clearly robotic aesthetics to avoid confusion with humans, while others push for more lifelike faces and gestures to make interaction intuitive. A widely shared clip from BostonDynamics B, tagged with #RoboticsInnovation, shows how carefully choreographed movements can make a machine seem playful rather than threatening. I suspect that the companies that get this social design right will have as much influence on the future of humanoids as those that push the hardest on raw technical performance.

More from MorningOverview