When astronomers pointed Hubble deep into our neighboring galaxy, they were not just chasing a prettier postcard of the night sky. The telescope’s ultra sharp view into Andromeda exposed a crowded, chaotic ecosystem of stars and shattered galaxies that hints at a violent past and a fated collision with our own. What looked like a serene spiral from afar turned out, under Hubble’s gaze, to be something far more unsettling: a detailed preview of the future of the Milky Way and a reminder that even “quiet” galaxies can be ruthless.

I see that disturbing revelation in two parts. First, Hubble’s images strip away the comforting illusion of distance, resolving individual suns and their histories in staggering detail. Second, the same data show that Andromeda is not a stable island in space but an active participant in a long running cycle of mergers, cannibalism, and eventual impact that will reshape everything we know about our own galactic home.

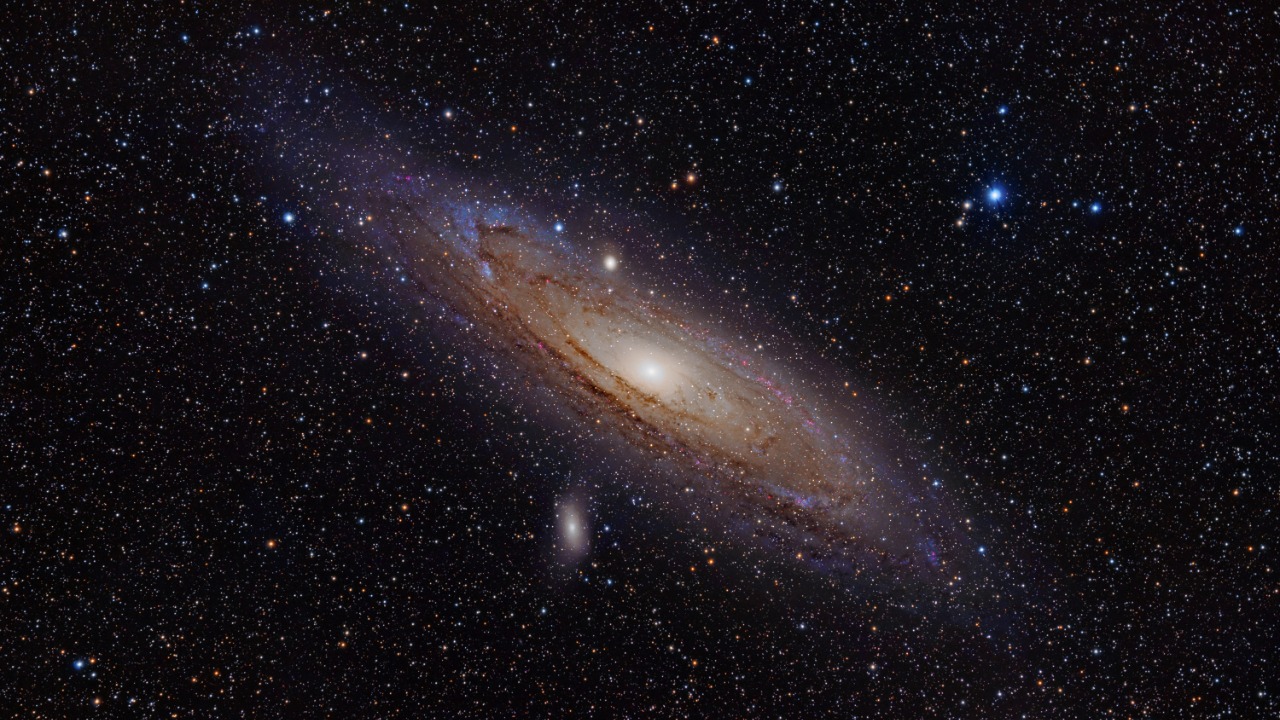

Hubble’s sharpest look at our neighbor

From my perspective, the most jarring thing about Hubble’s Andromeda work is how it collapses the scale of a galaxy into something almost intimate. In one campaign, astronomers used the telescope to pick out more than 200 m individual stars in Andromeda, turning what once looked like a smooth glow into a sea of distinct points. That level of detail lets researchers read the ages, motions, and chemical fingerprints of stars across the galaxy, effectively reconstructing its biography from scattered stellar clues.

The scale of the imaging effort is just as striking. Earlier work stitched together a 2.5-gigapixel mosaic of Andromeda, produced by The Hubble Space Telescope, capturing sweeping spiral arms, dense star fields, and the dust lanes that thread between them. When I look at that mosaic, I am not just seeing a pretty panorama. I am seeing a data set that lets scientists trace how waves of star formation, supernova explosions, and past collisions have shaped Andromeda’s current structure, region by region.

A chaotic history written in shattered galaxies

Once Hubble resolved Andromeda into its component stars, the galaxy’s past stopped looking orderly. Astronomers used the telescope to map the positions and motions of stars in several regions and found patterns that, as one team put it, “do not appear in computer simulations” of calm galactic evolution. Starting in late 2019, Starting Hubble spent two years on this work, combining images with precise measurement of stellar locations and motions. The resulting map shows streams and shells of stars that look like the fossil remains of smaller galaxies torn apart and absorbed into Andromeda’s disk and halo.

One likely culprit behind some of this debris is the compact satellite galaxy Messier 32, which current evidence suggests is the stripped down core of a once larger spiral system. In that picture, Andromeda did not just gently tug on a neighbor, it effectively peeled away the outer layers of Messier 32 and folded them into its own structure. When I follow that line of research, the galaxy’s smooth spiral arms start to look more like scars, each ring and ripple a sign of past encounters that were anything but peaceful.

Mini galaxies that refuse to die

Hubble’s unsettling story of Andromeda does not stop at the main disk. Around the galaxy, the telescope has cataloged a swarm of dwarf companions, and some of them behave in ways that challenge expectations. In standard models, these small satellites should have burned through their gas early, leaving behind old, red stars and little fresh activity. Instead, detailed imaging shows that Star formation in several of these dwarfs continued to much later times, suggesting that either they held on to their gas far longer than expected or they kept accreting fresh material from their surroundings.

That behavior echoes a broader class of so called “zombie” systems, galaxies that appear dead but still manage to feed on smaller neighbors and recycle material into new stars. In one study of such objects, researchers compared them to a Halloween monster, noting that they can eat up material from other smaller galaxies and then use that material, and sometimes even their own gas, to make new stars. The description of these Just like Halloween monsters is not just colorful language, it is a reminder that even galaxies that look quiet in visible light can be actively cannibalizing their surroundings, and Andromeda’s entourage appears to fit that pattern.

A disturbing preview of our own fate

For anyone living in the Milky Way, the most unsettling implication of Hubble’s Andromeda work is that it offers a preview of our own long term future. Dynamical studies that track the motions of both galaxies show that the fate of the Milky Way is effectively sealed. Six billion years from now, it will merge with Andromeda in a slow, complex collision that will stretch over hundreds of millions of years and ultimately produce the birth of a new galaxy. When I look at Hubble’s maps of shredded satellites and warped stellar streams in Andromeda, I am seeing the kind of gravitational violence that will eventually play out in our own sky.

Hubble’s wide field programs reinforce that sense of inevitability by framing Andromeda as part of a larger galactic ecosystem rather than a solitary neighbor. One survey described the scene as a kind of Eye View of Ecosystem, with The Andromeda Galaxy located 2.5 m light years away and surrounded by a retinue of satellites, gas flows, and dark matter structures. In that context, the coming Milky Way collision is not an isolated event but the next step in a long chain of interactions that have already reshaped Andromeda many times over.

What Hubble really revealed about Andromeda

When I pull together these threads, the disturbing part of Hubble’s peek into Andromeda is not a single shocking discovery but the cumulative picture of a galaxy built on disruption. Detailed analyses show that Hubble, the Hubble Space Telescope, has effectively opened a window into Andromeda Galaxy (M31)’s past, revealing the signatures of smaller galaxies that have shaped its current form. The stripped remains of Messier 32, the oddly persistent star formation in dwarf companions, and the intricate stellar streams all point to a system that has grown by repeatedly tearing apart its neighbors.

At the same time, that violence is the engine of creation. The same mergers that shred satellites also trigger new waves of star birth, stir up gas, and redistribute heavy elements that will eventually seed planets. In that sense, Hubble’s view of Andromeda is unsettling precisely because it is honest. It shows a universe where beauty and destruction are inseparable, where our own Milky Way is on track to be both victim and beneficiary of the same processes that sculpted our nearest large neighbor. For me, that realization is the real shock hidden inside those exquisite images: the calm spiral in the sky is not a refuge from chaos, it is proof that cosmic upheaval is the rule, not the exception.

More from Morning Overview