The first time a real retractable plasma blade flared to life on camera, it looked less like a fan project and more like a physics experiment that had slipped its leash. This was not a glowing plastic tube or a digital effect, but a column of superheated gas shaped into a blade and hot enough to chew through metal. In chasing that spectacle, a small team of engineers discovered how quickly a clever idea can run into the hard limits of heat, power, and safety.

From viral stunt to engineering crucible

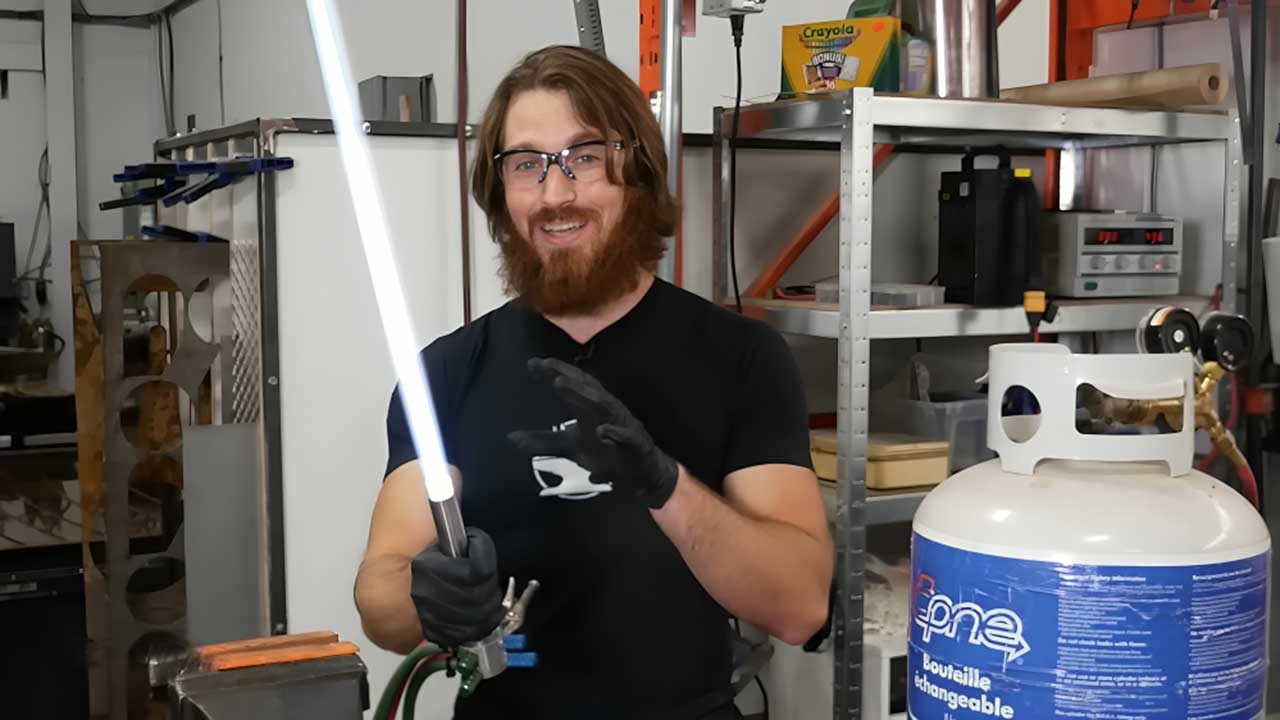

What began as a cinematic homage rapidly turned into a stress test for modern fabrication. In a widely shared clip, the device is framed almost like a sports highlight, with the plasma blade cutting through obstacles the way a running back slices in between two Texans defenders, a visual shorthand for just how little resistance the material offers once the gas is fully energized, as seen in that footage. The device is introduced with a blunt warning that it is not a toy, and the tone is closer to a lab demonstration than a cosplay reveal.

In the same sequence, the narrator underlines that this is not a prop, a toy, or a visual effect, but a real column of ionized gas, a moment that feels like science fiction colliding with reality and is captured in the description. That insistence is not bravado, it is liability management: once you move from LEDs to actual plasma, every design choice becomes a negotiation with thermodynamics and failure modes that consumer gadgets are rarely asked to confront.

Inside the retractable plasma mechanism

At the heart of the build is a simple but unforgiving idea: confine a stream of burning gas into a narrow, laminar column and then retract it on command. The team behind the project had already experimented with a Plasma based Lightsaber and a Lightsaber Pike, both of which used open jets of superheated gas to slice through targets. Turning that into a retractable system meant packaging fuel delivery, ignition, and flow control into a hilt that could be held in one hand without cooking the user.

The breakthrough, and the breaking point, came when the builders integrated a telescoping assembly that could extend and withdraw the flame column like a piston. According to a step by step breakdown, Next they integrated a retractable mechanism into the hilt of the Lightsaber, allowing the plasma blade to extend and retract while still being capable of cutting through various materials. That combination of motion and extreme temperature forced compromises in wall thickness, seals, and cooling that would be trivial at room temperature but become existential when the working fluid is hot enough to melt steel.

The physics of a “real” lightsaber

To make the blade behave like a solid object, the engineers leaned on fluid dynamics rather than fantasy. The design uses the principal of laminar flow to turn a highly concentrated stream of propane gas into a plasma column, a detail spelled out in a technical explainer that begins, with deliberate understatement, With the principal of laminar flow. By keeping the gas stream smooth and coherent, the builders can shape it into a narrow, sword like profile instead of a diffuse torch.

Color, that most iconic part of any fictional blade, is handled with chemistry rather than LEDs. The blade can be rendered different colors by adding specific compounds to burn at the base, with boric acid creating a Luke style green when mixed into the fuel, a flourish documented in coverage of how Luke inspired hues are achieved. Those touches make the device feel closer to the movies, but they also add another layer of variables to manage in a system that is already operating at the edge of controllability.

From YouTube spectacle to industrial cautionary tale

The person most associated with this experiment is James Hobson, a Canadian engineer who has built a career on translating fictional gadgets into working prototypes. In an interview about his earlier builds, James Hobson stressed that his lightsaber is not a toy and described how he and his team at Hacksmith engineered a hyper realistic plasma lightsaber that can cut through steel and even threaten a bank vault door. That same ethos underpins the retractable version, which takes the spectacle that made his earlier builds viral and compresses it into a more compact, more temperamental package.

What looks like a YouTube stunt is, in practice, a live fire test of how far consumer grade components can be pushed before they fail. The retractable plasma blade demands a fuel system that can deliver high flow rates without leaks, a power source that can drive ignition reliably, and a chassis that can survive repeated thermal cycling. Each of those subsystems has to work in concert, and any misalignment risks turning the hilt into a blowtorch pointed at the user’s own hand, a risk that grows as the design is refined for portability and showmanship.

When plasma tools fail in the real world

The hazards are not hypothetical, as the medical world has already learned with surgical plasma devices. A review of regulatory reports on the PEAK PlasmaBlade found that from these 361 M device records, a total of 424 adverse events were extracted, and Of the 424, 348, or 82.1%, were classified as device malfunctions, figures laid out in an analysis of Of the complications. Those numbers come from a tightly regulated clinical environment, with trained surgeons and hospital protocols, yet the technology still produced hundreds of documented failures.

Set against that backdrop, a retractable plasma blade built for entertainment looks less like a harmless curiosity and more like a case study in unmanaged risk. The same physics that allow a surgical PlasmaBlade to cut tissue with precision also govern a propane fueled lightsaber that can slice through steel. When a device that is explicitly described as not a prop and not a toy is wielded in a workshop for an audience of millions, as in the Jan and What clips that frame the project, the line between demonstration and danger becomes very thin. In pushing for a retractable, handheld plasma blade, the builders did not just chase a childhood fantasy, they walked straight into the same engineering constraints that have humbled far more established industries.

More from Morning Overview