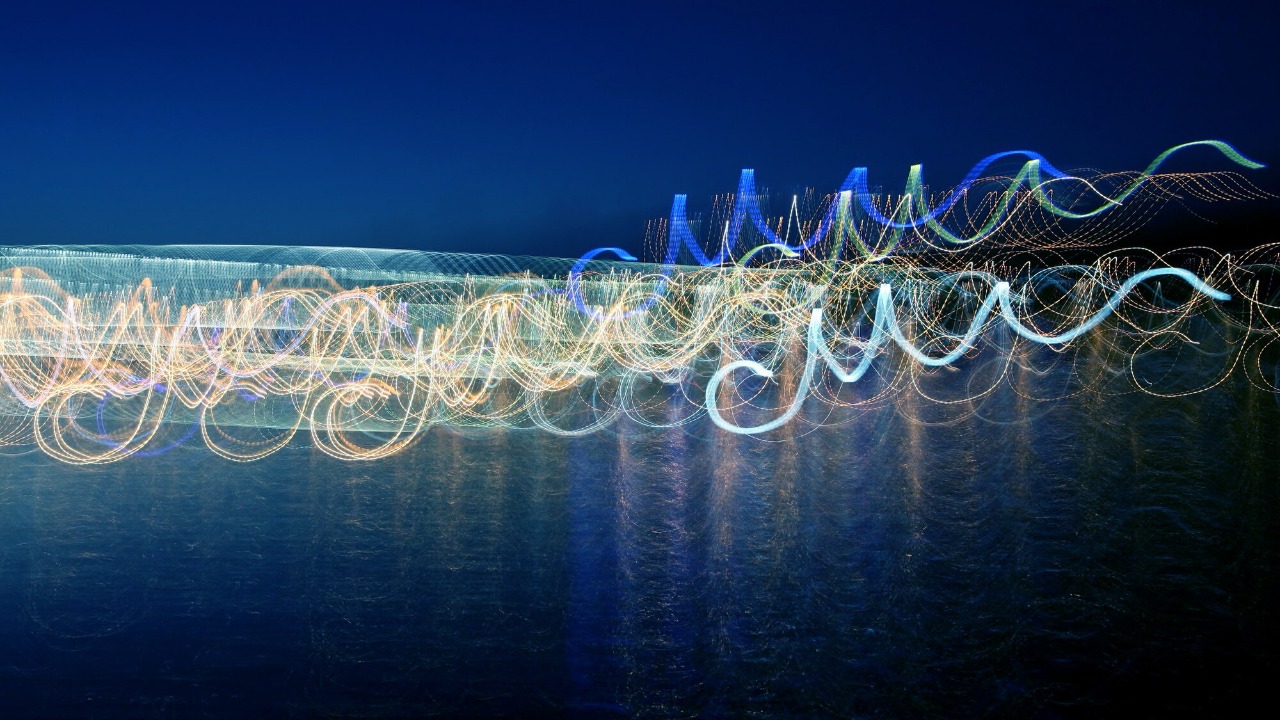

For more than a century, scientists have known that waves can behave in ways that seem to defy common sense, from freak walls of water in the open ocean to ghostly ripples inside atoms. What has changed in the past few years is the realization that many of these puzzles yield to the same idea: hidden networks of interacting waves. By treating the sea, the shoreline and even quantum particles as tangled webs of connections, researchers are finally resolving mysteries that once looked unsolvable.

I see a pattern emerging across fields that rarely talk to one another. Oceanographers, quantum physicists and mathematicians are converging on a shared language of interference, randomness and connectivity, and that shift is turning vague metaphors about “wave chaos” into concrete models that can be tested, visualized and, in some cases, engineered.

From classroom ripples to a network view of interference

The modern story of waves still begins with a deceptively simple picture: light or water passing through two openings and creating a striped pattern of bright and dark bands. In 1801, the double slit experiment by Young revived the idea that Light behaves as a wave, vindicating the earlier intuition of Huygens that every point on a wavefront can act like a source of new ripples. That picture, of many tiny sources adding up, is already a kind of network, even if it was not described that way at the time.

What has changed is how explicitly researchers now lean on that network perspective. Popular explainers by communicators such as Sanderson start from the visual idea that a complex wave is built from many simpler components, each with its own frequency and phase. That approach mirrors what working scientists now do when they model sound editing, ocean swells or electromagnetic pulses as overlapping contributions in a shared network of interactions rather than as isolated, smooth curves.

Rogue waves and the tangled web of the open ocean

Nowhere is the network character of waves more visceral than in the sudden appearance of rogue waves, the towering walls of water that can rise out of an otherwise ordinary sea. For decades, these monsters were treated as statistical flukes, but an international team led by Fedele, a longtime skeptic of conventional explanations, has reframed them as the natural outcome of a crowded field of interacting swells. In that view, each wave is a node in a shifting network, and rare alignments can funnel energy into a single crest that is much larger than the rest.

That same logic extends toward the coast, where the geometry of the seafloor and shoreline reshapes how waves connect with one another. Work on Infragravity Waves and shows that natural wave fields are not monolithic but instead contain slower, long-period components that can trap and release energy along the coast. There is a further, very important consequence of the fact that these random fields are built from many modes: the apparent “background” can suddenly reorganize, amplifying certain frequencies and setting the stage for extreme events.

Hidden structures beneath tsunamis and tiny quakes

That sensitivity to structure is now central to how geophysicists think about tsunamis. Rather than treating a tsunami as a single pulse racing across the ocean, researchers map how it couples to the crust, the continental slope and even subtle faults that only reveal themselves through tiny tremors. Recent work on Tiny Earthquakes Are a Dangerous Secret Beneath California shows how small seismic events can trace out hidden faults that, in turn, shape how tsunami waves might focus or disperse along the coast. In that sense, the coastline and the underlying rock form a fixed network that incoming waves must navigate.

Those same studies highlight how much remains unknown. The Latest Headlines on tsunami research emphasize that Scientists are still uncovering how complex bathymetry, sediment layers and fault geometry interact with long waves. Yet the direction of travel is clear: instead of relying on simple, one dimensional models, teams now build simulations where each patch of seafloor and each segment of a fault is a node in a coupled system. The resulting patterns of amplification and shadowing are not accidents, they are signatures of the network itself.

Quantum waves and the reality of the invisible network

The network idea becomes even more striking when I follow it down to the quantum scale. Inside atoms, the so called quantum wave does not slosh around like water, but it still encodes how different possibilities interfere. Work by Pusey and Hardy argues that the wave function is not just a bookkeeping device but a very weird kind of real, a structure that genuinely exists even if it cannot be seen directly. On the one hand, that makes the quantum wave feel more concrete, on the other, it forces us to accept that reality itself may be organized as a web of probabilities rather than solid trajectories.

That philosophical shift has practical consequences. A Vermont research team recently cracked a 90-year-old puzzle in quantum physics by engineering a system where delicate interference patterns could be controlled and measured with unprecedented precision. Their work is not just a curiosity, it is expected to fuel next generation precision tools that rely on the stability of quantum networks, from atomic clocks to sensors that can detect minute changes in gravity or electromagnetic fields.

Mathematical networks that tie the story together

Behind these advances sits a quieter revolution in pure mathematics. At 17, Hannah Cairo stepped into this landscape and, according to reporting on her work, helped resolve a long standing question in number theory that intersected with wave behavior. Her story is framed within a broader effort in Mathematics to understand how Networks Hold the Key to a Decades Old Problem About Waves, showing that even abstract equations can encode hidden connectivity. In that context, the entities labeled Aug and Also in the reporting mark not just dates or asides but milestones in a growing recognition that wave problems are often network problems in disguise.

What I find striking is how these mathematical insights loop back to the physical world. Techniques developed to study graphs and number theoretic structures now inform models of random seas, seismic fields and quantum devices. When oceanographers refine their statistics of rogue waves, when geophysicists map tsunami pathways, or when quantum engineers stabilize interference, they are all, in effect, probing the same underlying idea: that waves reveal their deepest secrets only when we see them as part of a connected whole. The mystery was never just in the crest or the trough, it was in the hidden network that links them.

More from Morning Overview