Subtle changes in the gut can signal a higher risk of cancer long before a tumor shows up on a scan. Researchers are increasingly focused on these quiet red flags, from shifts in bowel habits to microscopic traces of damage in the cells lining the colon. The emerging picture is that a “hidden” warning sign in the digestive tract is not one thing, but a cluster of symptoms and biological clues that, taken together, can sharply raise a person’s odds of developing colorectal disease.

As I look across the latest research, the message is blunt: ignoring persistent gut changes is no longer an option. Scientists are tying early digestive symptoms, molecular fingerprints in tissue and blood, and even specific bacteria in the mouth and intestines to a higher likelihood of aggressive cancers later on. The challenge now is helping people recognize which signals matter and getting those signs checked before they turn into a life‑threatening diagnosis.

The gut as cancer’s early battleground

One of the most striking shifts in cancer science is the way the digestive tract has moved to center stage. I see that in work showing how the intestines act as a kind of early battleground where environmental exposures, diet, and immune responses collide. In research described as Mystery of What, scientists have zeroed in on the Gut as a focal point for the forces Causing Young People to develop malignancies that used to be seen mainly in older adults. Researchers are not just looking at tumors themselves, but at the way food additives, antibiotics, and early‑life exposures may reshape the microbiome and the intestinal lining over decades.

That same body of work treats the digestive system as a living archive of a person’s history. When I read about how investigators are combing through people’s bodies and childhood histories for culprits, it is clear they are treating the Cancer Leads that show up in the colon or rectum as the end result of a long chain of events. The Gut becomes the place where subtle inflammation, immune misfires, and microbial imbalances quietly accumulate until a cell finally tips into malignancy. In that context, a nagging gut symptom is not just an annoyance, it is a potential clue that this long process is already under way.

The “hidden” symptoms you should not brush off

For all the attention on high‑tech biomarkers, some of the most important early signs of colorectal trouble are still the ones people can feel. Experts warn that Colorectal cancer often announces itself with a handful of deceptively ordinary complaints that many patients dismiss or try to self‑treat. Among the most common are persistent Stomach pain, unexplained changes in bowel habits, rectal bleeding, and a sense that the bowel does not fully empty. These are the kinds of issues that might be blamed on stress, a new diet, or hemorrhoids, yet they can be the first outward sign of a tumor growing silently in the colon.

What makes these symptoms so dangerous is not their intensity but their persistence. I have heard gastroenterologists describe patients who lived with altered bowel patterns or intermittent bleeding for months before seeking help, only to discover advanced disease. In reporting on these patterns, clinicians emphasize that any ongoing combination of abdominal discomfort, altered stool caliber, or blood in the stool should trigger a conversation with a doctor, not another round of over‑the‑counter remedies. When specialists outline these four hidden warning signs of Colorectal disease, they are urging people to treat Stomach and bowel changes as a prompt for evaluation, a point underscored in guidance on hidden warning signs.

Microscopic clues: how molecular epidemiology spots risk early

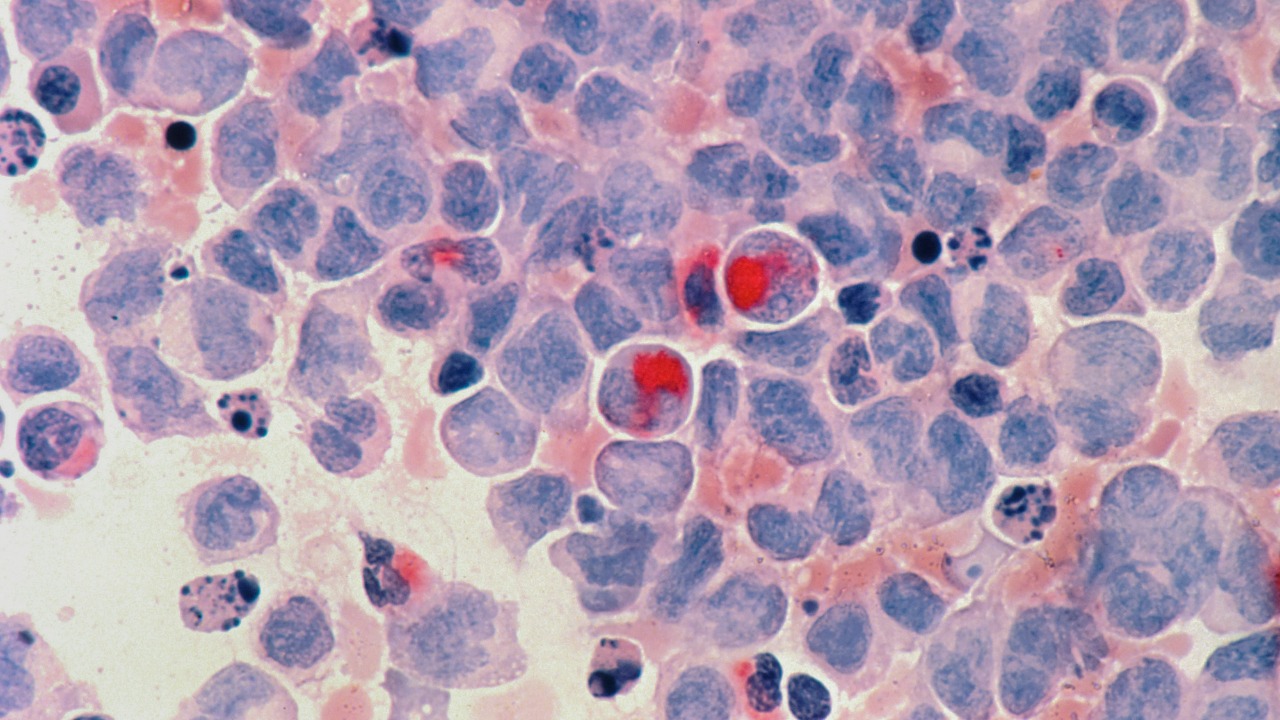

Beyond symptoms, the next wave of early warning is happening at the microscopic level. In the field known as Molecular epidemiology, scientists are mapping how specific exposures leave chemical scars on DNA and proteins in the gut. It ( Molecular epidemiology ) also identifies biological signs, or biomarkers, that may indicate increased risk long before a tumor forms. Some of these markers reflect the direct effects of carcinogens on cells, while others capture how the body’s repair systems respond to that damage. By tracking these subtle shifts in blood, stool, or tissue samples, researchers can flag people whose colons are already under abnormal stress.

What I find especially important is that these biomarkers are not abstract lab curiosities, they are starting to shape real‑world screening strategies. When investigators talk about using Molecular tools to pick up the effects of carcinogens, they are describing a future in which a routine test could reveal whether a person’s gut has been quietly accumulating risk for years. Some markers, such as specific DNA adducts or patterns of gene expression, can act like small banners that signal heightened vulnerability even when imaging looks normal. Work in this area, detailed in analyses of Molecular approaches, is pushing clinicians to think about cancer risk as something that can be measured and tracked, not just guessed from age and family history.

When mouth microbes turn colon cancer more aggressive

Another underappreciated warning sign is hiding not in the intestines themselves, but in the mouth. Researchers have uncovered evidence that common oral bacteria can migrate to the colon and change the behavior of tumors that form there. In one line of work, scientists found that certain microbes normally found in dental plaque were present inside colon cancers and appeared to make those cancers more invasive. The implication is that the microbial fingerprint of a person’s mouth and gut is not just a passive background factor, it can actively shape how dangerous a malignancy becomes.

That connection between oral health and intestinal disease is more than a curiosity. When I read that Colon cancer could be made more aggressive by common oral bacteria, it reframes everyday issues like gum disease or chronic mouth infections as potential contributors to serious illness later on. It suggests that maintaining a healthy oral microbiome might be one more lever for reducing risk, alongside diet, exercise, and screening. The fact that investigators have traced specific bacterial strains from the mouth into tumor tissue, as described in research on Colon tumors, underscores how interconnected the body’s ecosystems really are.

What I watch for, and what you can do next

Putting these threads together, I see a pattern that changes how I think about gut health. The digestive tract is not a black box that suddenly produces cancer out of nowhere, it is a dynamic system that sends up flares long before a scan turns positive. Persistent bowel changes, unexplained Stomach pain, and rectal bleeding are the visible tip of that iceberg. Beneath the surface, Molecular markers and shifts in the microbiome, including bacteria that travel from the mouth to the colon, are already reshaping the risk landscape. The hidden warning sign in the gut is really the convergence of these signals, from symptoms you can feel to microscopic changes you cannot.

In practical terms, that means taking a more proactive stance. I pay close attention to how long a symptom lasts, not just how severe it feels, and I encourage readers to do the same. If bowel habits change for more than a few weeks, if there is any recurring blood in the stool, or if abdominal discomfort keeps returning without a clear cause, it is time to push for evaluation rather than waiting it out. At the same time, staying engaged with routine screening, asking about emerging Molecular tests when appropriate, and treating oral health as part of cancer prevention all help shift the odds. The science is clear that the gut holds crucial early clues; the real question is whether we choose to act on them while there is still time to change the story.

More from Morning Overview