In a quiet freshwater pond in Ibaraki Prefecture near Tokyo, researchers have pulled from the water a microscopic giant that is forcing biologists to rethink how complex life began. The newly identified giant virus, named ushikuvirus, infects amoebae yet carries an unusually large genome and a way of living inside its host that looks more like a long-term partnership than a smash‑and‑grab attack. For scientists who have spent decades arguing over whether viruses helped build the first complex cells, this strange organism offers some of the clearest evidence yet that the story of life’s origins may be inseparable from the story of viruses.

Instead of behaving like a typical pathogen that kills quickly and moves on, ushikuvirus appears to settle in, reshape its host’s biology, and potentially trade genes in both directions. That behavior, combined with its genetic kinship to other giant viruses linked to the evolution of cell nuclei, is why some researchers now see this Japanese pond as a living window into the deep past of multicellular life.

The strange biology of a “giant” virus

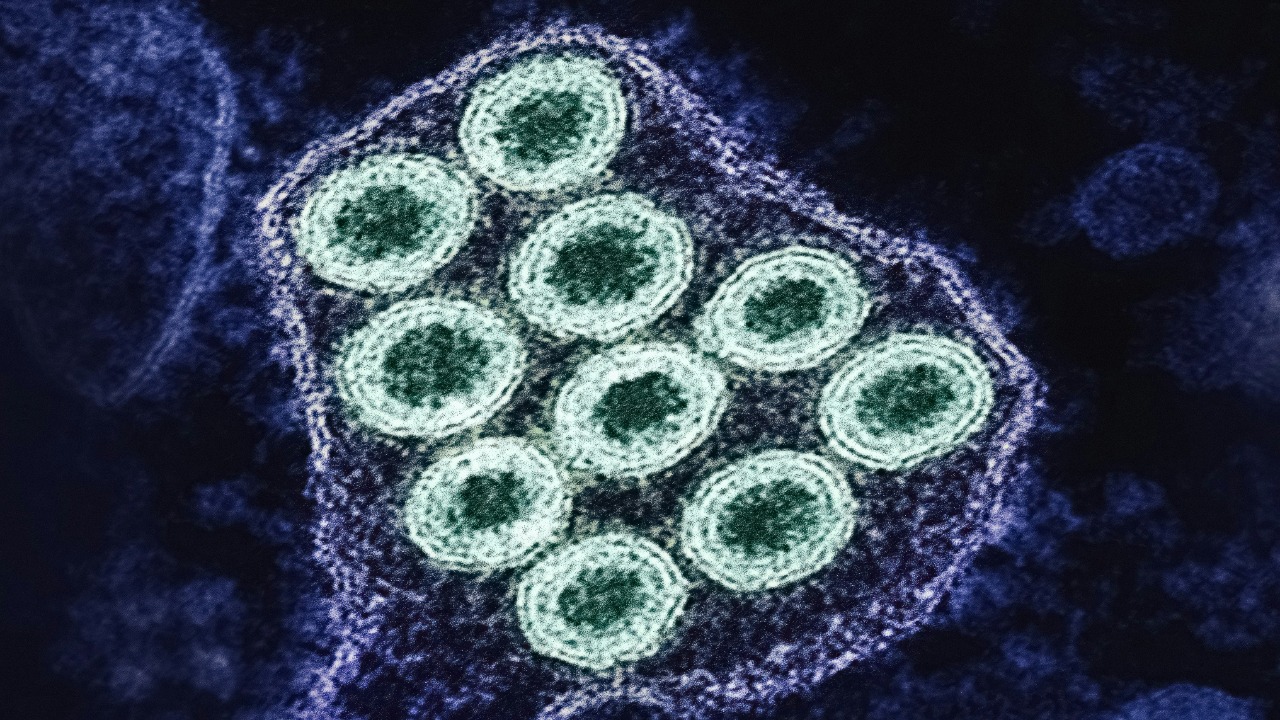

Ushikuvirus belongs to a class of outsized pathogens that blur the line between virus and cell. Under an electron microscope, these particles are large enough to rival small bacteria, and their DNA payload is correspondingly hefty. In laboratory infections of amoebae, scientists watched this Giant Virus with a Massive Genome and Unusual Infection Strategy swell its hosts to abnormal sizes rather than immediately bursting them open. The infected amoeba cells balloon, their internal architecture reorganized around viral factories that quietly copy ushikuvirus genomes.

That slow‑burn approach is what sets ushikuvirus apart. Instead of killing the host, the virus set up a long-term presence inside the cytoplasm, and over time acquired essential genes from the host, according to researchers at Tokyo University of Science who described how this persistent lifestyle may have allowed the virus to accumulate functions usually associated with cellular organisms. In their view, this kind of stable coexistence, described in detail in a Instead of scenario, is exactly the sort of relationship that could have nudged early microbes toward greater complexity.

From medusavirus to ushikuvirus: a growing viral family tree

Ushikuvirus did not appear out of nowhere. It is closely related to medusavirus, a large DNA virus first isolated from hot spring water in Japan that infects Acanthamoeba castellanii. When medusavirus was characterized, scientists noted that it carried a full set of histone homologs, the DNA‑wrapping proteins that are central to how eukaryotic cells organize their genomes. The original description of medusavirus, which detailed how it hijacks amoebae and reshapes their nuclei, framed it as a potential missing link between simple viruses and the complex machinery of eukaryotic chromatin, as laid out in the Medusavirus report.

Taxonomically, ushikuvirus sits within the family Mamonoviridae, which was formally assigned to group several medusavirus strains that infect acanthamoeba. Genomic comparisons show that ushikuvirus is closely related to these earlier isolates, yet it also carries its own distinctive set of genes and infection traits. A detailed ABSTRACT on Mamonoviridae notes that members of this family share unusual replication strategies and gene repertoires that are not easily explained by standard viral evolution. By extending this family tree into a new ecological niche, the Japanese pond where ushikuvirus was found, researchers can now compare how these related giants behave across different environments and hosts.

A controversial hypothesis about the origin of the nucleus

The discovery of ushikuvirus has revived a Controversial Hypothesis that has hovered at the edge of mainstream biology for a quarter century. In 2001, Bell and Takemura, along with Australian researcher Philip Bell working independently, proposed that the nucleus of eukaryotic cells might have originated from a large DNA virus that took up residence inside a prokaryote‑like ancestor. According to this viral eukaryogenesis model, the viral compartment gradually evolved into the membrane‑bound nucleus, while the host cell supplied energy and basic metabolism. The core of this idea, summarized in a DNA virus overview, is that complex life did not simply add pieces to a bacterial chassis, it may have merged with a virus.

For years, this scenario was largely theoretical, supported by scattered hints in viral genomes and cell biology. The new Japanese giant, however, gives the hypothesis fresh empirical weight. A recent analysis of ushikuvirus, described as a Controversial Hypothesis in its own right, emphasizes that members of the Mamonoviridae family possess genes and replication features that resemble components of modern eukaryotic cells. If a virus like ushikuvirus can establish a durable, gene‑sharing relationship with its host, it becomes easier to imagine how a similar partnership in the deep past could have crystallized into the first nucleus.

Why a Japanese pond matters for multicellular life

What makes this particular pond so important is not just that it harbors a giant virus, but that the virus’s behavior hints at how multicellular life might have emerged. When ushikuvirus infects amoebae, scientists observed that the cells do not simply die; they grow larger, their internal compartments reorganize, and the viral genome persists. Reporting on this work notes that the Ushikuvirus News Release from Tokyo University of Science frames the infection as a model for how early viruses might have reshaped primitive cells. By pushing host cells to expand and tolerate a foreign genetic passenger, ushikuvirus effectively rehearses the kind of symbiotic arrangement that could have set the stage for larger, more complex organisms.

Other coverage of this work underscores that the Japanese Pond May Hint at Multicellular Life by showing how a virus can drive its host toward greater size and structural complexity without immediate lethality. In one account, researchers describe how this Giant Virus Discovered in a Japanese Pond May Hint at the Origins of multicellular life by offering a living example of virus‑driven cell remodeling. If similar interactions occurred repeatedly in ancient microbial communities, they could have produced the first steps toward stable cell lineages with specialized internal structures, a prerequisite for tissues, organs, and eventually animals and plants.

Rewriting the story of viruses and complex cells

For much of modern biology, viruses have been cast as genetic parasites that sit outside the tree of life, hijacking cells but contributing little to their long‑term evolution. The growing catalog of giant viruses is forcing a revision. Earlier work on medusavirus showed that amoebae are promising natural hosts and that lateral gene transfer between virus and host is extensive, with the virus carrying a full set of histone homologs that mirror eukaryotic proteins, as detailed in an Apr analysis. Ushikuvirus extends that picture by demonstrating that a related giant can maintain a long‑term presence in the cytoplasm while accumulating host‑derived genes, suggesting that such viruses are not evolutionary dead ends but active participants in shaping genomes.

Several reports emphasize that this Giant Virus, Previously Unknown to Science, May Help Unlock the Mystery of Life’s Origins by providing a concrete system in which to test ideas about viral contributions to cell complexity. One account describes how This Giant Virus, Previously Unknown and rooted in Science, May Help Unlock the Mystery of Life and its Origins by bridging gaps between viral and cellular biology. Another notes that scientists studying the pond have watched amoeba cells swell dramatically after infection, a detail echoed in coverage of how Scientists saw a Giant virus make amoeba cells grow instead of burst. Together with broader summaries that describe how a New Giant virus in Jan may rewrite thinking about the origin of complex life, these findings suggest that viruses like ushikuvirus are not just passengers in evolution’s story but co‑authors.

More from Morning Overview