Astronomers have pulled a frozen, Earth-sized world out of archival data from the retired Kepler Space Telescope, revealing a planet candidate that circles its star roughly once a year and could host conditions suitable for life. The object, described as an ice-cold twin of our own planet, was hiding in plain sight in observations that ended years ago but are still yielding discoveries. Its orbit, size and frigid temperature make it one of the most intriguing Earth analogues yet identified beyond the Solar System.

The find underscores how much science remains locked inside old survey records, waiting for better algorithms and fresh eyes. By combining Kepler’s long baseline of precise brightness measurements with follow-up work from ground-based observatories and other missions, researchers are now sketching the profile of a world that is at once familiar and profoundly alien.

From faint dips to a “Cool Earth” candidate

The new world first emerged as a subtle pattern in the light curve of a relatively dim orange star, a tenth magnitude K dwarf that Kepler monitored during its extended K2 campaign. In a detailed analysis, an international team described it as a cool Earth-sized planet that periodically crosses, or transits, the face of its host star. Each transit produces a tiny, repeatable dimming that reveals the planet’s presence and allows astronomers to estimate its radius with surprising precision. Because the star is a K dwarf, smaller and cooler than the Sun, a planet of roughly Earth’s size can block a measurable fraction of its light.

The discovery paper characterizes the object as a “Cool Earth, Planet Candidate Transiting a Tenth Magnitud” star, language that captures both its temperature regime and the method used to find it. NASA highlighted the same system as an ice-cold Earth analogue, noting that the transit signal was strong enough for an international science team to publish a dedicated study of this planet candidate transiting a relatively faint but well-behaved K dwarf. I see that combination of a modest star and a clean transit pattern as a key reason the team can speak so confidently about the planet’s size and orbital period.

Kepler’s long shadow and the power of surveys

What makes this discovery especially striking is that it comes years after the Kepler Space Telescope stopped collecting data. The spacecraft, designed to survey a slice of the Milky Way for planetary transits, retired in 2018 after exhausting its fuel. Yet its archive continues to deliver new worlds as scientists refine their search techniques and revisit old targets. Reports on the frozen Earth candidate emphasize that the Kepler Space Telescope was built to stare at thousands of stars at once, hunting for the tiny brightness dips that signal a planet passing in front of a distant star outside our Solar System.

Researchers mining those archives describe the new object as a possible ice-cold Earth discovered in the records of the retired observatory, a reminder that large surveys can keep paying scientific dividends long after the hardware falls silent. In coverage of the find, astronomers stress that scientists continue to comb Kepler’s data for subtle, long-period signals that earlier pipelines might have missed. I read that persistence as a sign that the community now sees archival work as central to exoplanet science, not just a side project.

A yearlong orbit and an ice-cold climate

One of the most tantalizing aspects of the new planet candidate is its orbital period, which is close to a full year. At a recent Rocky Worlds conference, researchers described a newly discovered world with a yearlong orbit that is almost exactly Earth-size, a configuration that immediately invites comparison with our own planet. The report notes that this Earth-size planet sits at a distance from its star that keeps it in a cold regime, with surface temperatures likely well below freezing if it has an atmosphere similar to Earth’s. That combination of Earth-like size and a long, cold year is what earns it the “ice-cold Earth” label in technical and popular accounts.

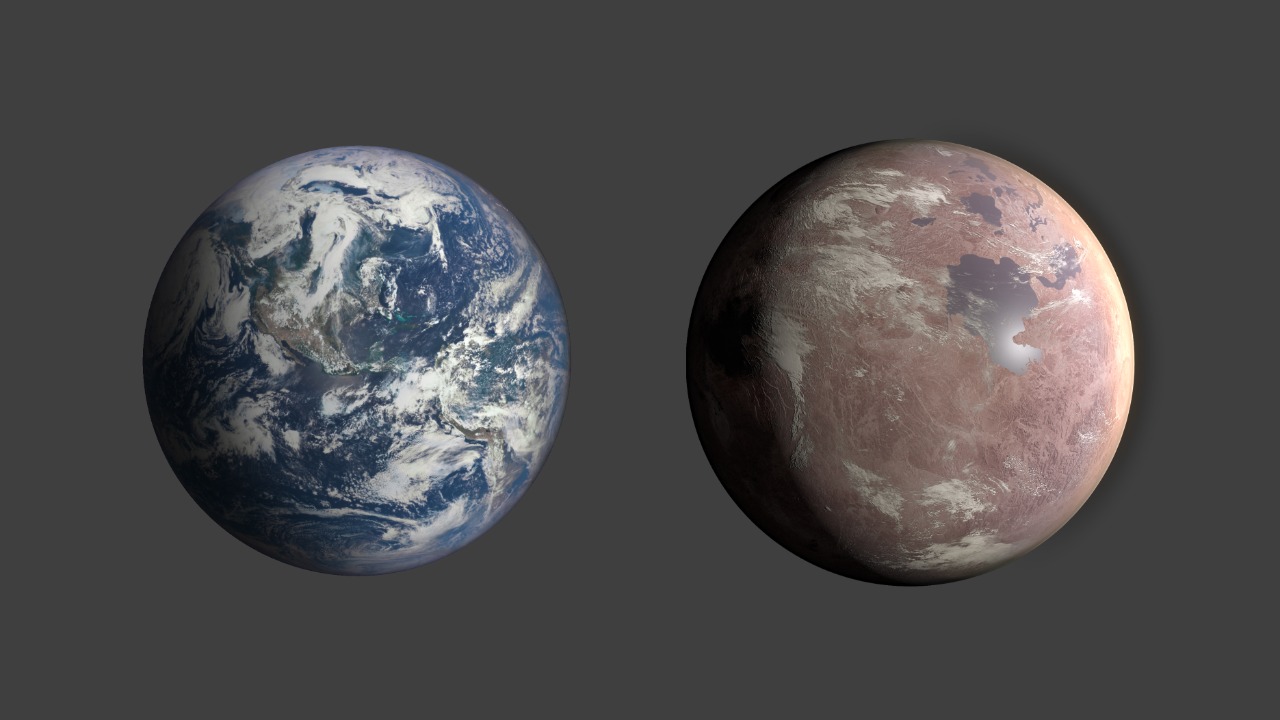

NASA’s own summary frames the object as an ice-cold Earth candidate, emphasizing that its orbit places it in a region where water could exist as ice or perhaps liquid under the right atmospheric conditions. I see that as a subtle but important point: the planet is not a temperate twin of modern Earth, but rather a frozen sibling that might resemble our world during a deep ice age. Its climate, if it has one, would depend on greenhouse gases, cloud cover and surface reflectivity, all factors that remain unknown from transit data alone.

How “Earth-like” is a frozen twin?

As soon as a planet is described as an Earth twin, the question of habitability follows. Some coverage of the broader exoplanet landscape highlights HD 137010 b, a newly discovered world that might be the closest thing we have to Earth’s twin, with reports noting that this exoplanet could be one of the most promising Earth-like candidates yet Published. Another account, framed under the banner “Astronomers Just Discovered an Ice-Cold Earth-Like Planet, and It Could Harbor Life,” describes how astronomers just discovered an Ice, Cold Earth Like Planet and argue that It Could Harbor Life. I read those comparisons as a reminder that “Earth-like” can mean different things: similar size, similar temperature, or similar potential for liquid water.

In the case of the frozen Kepler candidate, the resemblance lies primarily in size and orbital period, not in a comfortable climate. Reports that describe scientists discovering a potentially habitable Earth-like planet candidate stress that habitability is a spectrum, shaped by stellar type, planetary mass and atmospheric composition. I see the frozen twin as sitting on the cold edge of that spectrum, where life might be possible under thick blankets of greenhouse gases or beneath ice-covered oceans, but where the surface would be far from the mild conditions humans enjoy on Earth today.

NASA, European follow-up and the road ahead

NASA has already begun to frame the frozen Earth candidate as a test case for future missions. A social video circulating on Jan 28 notes that Nasa has announced a striking new planet candidate buried in old Kepler data and that Tests or the European keyops mission may catch the next transit. That reference to European follow-up hints at a growing partnership in exoplanet characterization, where space telescopes on both sides of the Atlantic coordinate to refine orbital periods, measure masses and, eventually, probe atmospheres. I see the mention of Tests and a European mission as a sign that planners are already thinking about how to schedule scarce observing time around such long-period targets.

At the same time, popular accounts keep circling back to the broader narrative that astronomers just discovered an ice-cold Earth-like planet and that It Could Harbor Life, a phrase repeated in coverage that treats the frozen twin as part of a larger wave of discoveries. One such report, under the banner “Astronomers Just Discovered an Ice-Cold Earth-Like Planet, and It Could Harbor Life,” underscores that Astronomers Just Discovered an object that fits the Ice, Cold Earth, Like Planet, It Could Harbor Life framing. Another passage in the same coverage notes that a newly discovered exoplanet, HD 137010 b, might be the closest thing we have to Earth’s twin, reinforcing the idea that a family of Earth-sized, potentially habitable worlds is starting to emerge from the data. That report adds that this exoplanet is one of the most promising planets out there like ours, a phrase that captures the excitement driving both NASA and European teams to keep pushing deeper into the Kepler archive.

More from Morning Overview