Scientists have long suspected that industrial pollutants might help trigger multiple sclerosis, but the latest evidence raises the stakes. A large Swedish study now links everyday exposure to so‑called “forever chemicals” with sharply higher odds of developing the neurological disease, suggesting that the chemicals embedded in nonstick pans, waterproof jackets, and food packaging may be quietly reshaping brain health. The findings do not prove cause and effect, yet they are strong enough that I see them as a clear warning signal for regulators, clinicians, and anyone living with MS risk in their family.

The research zeroes in on per‑ and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, along with related industrial pollutants called PCBs, which linger in the body and environment for years. By tying higher blood levels of these compounds to MS diagnoses even after accounting for known genetic and lifestyle risks, the study reframes forever chemicals from a vague toxic threat into a concrete factor in a specific, life‑altering disease.

What the new MS study actually found

At the center of the alarm is a case‑control study from Sweden that examined blood samples from people newly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and compared them with samples from people without the disease. Researchers measured a wide panel of PFAS and PCB metabolites and found that people with higher combined exposure had significantly greater odds of MS, a pattern that held up even after adjusting for established risk factors such as smoking and key immune‑related genes. The work, led by scientists at Uppsala University, reported that people exposed to both PFAS and PCBs were more likely to be diagnosed with MS, a link detailed in a university release and echoed in broader coverage of PFAS and PCB.

The study did not look at vague environmental contact but at concrete chemical signatures in blood. Investigators reported that an increase in total exposure to these compounds was linked to higher odds of MS, even after accounting for previously known lifestyle and genetic risks, as summarized by the Multiple Sclerosis Foundation. A related summary in Spanish underscored that the researchers found the same pattern when they modeled total exposure, noting that “the researchers found an increase in total exposure was linked to higher odds of MS,” a point highlighted in a Spanish‑language brief. An independent overview of the work emphasized that these associations remained even after adjustment for lifestyle factors and MS‑related HLA variants, underscoring an independent effect of PFAS and PCBs, as noted in a neurology report on.

Inside the Swedish research: who was studied and how

To understand why these results are drawing so much attention, it helps to look at the study design. The project, led by researcher Kim Kultima in Sweden, analyzed blood samples from about 900 people who had recently been diagnosed with MS and compared them with matched controls. By focusing on people at the point of diagnosis, the team reduced the risk that long‑term disability or treatment might distort chemical levels. The analysis covered a mixture of PFAS compounds and PCB metabolites, reflecting the reality that people are rarely exposed to a single pollutant in isolation.

Researchers then modeled how different combinations of chemicals related to MS odds. They found that several substances contributed to the risk signal, and that the mixture of PFAS and PCBs mattered more than any single compound, a point highlighted in a technical summary of the mixture analysis. A detailed news release on the project stressed that exposure to a mixture of PFAS and PCBs was associated with higher odds of being diagnosed with MS, reinforcing that it is the combined chemical burden, not a single villain, that appears to be driving the association, as described in an international summary.

From nonstick pans to the nervous system

What makes these findings so unsettling is how ordinary the sources of exposure are. PFAS are used to make nonstick cookware, waterproof clothing, stain‑resistant carpets, and grease‑resistant food packaging, and they have earned the nickname “forever chemicals” because they do not readily break down in the environment or the human body. Coverage of the MS study has repeatedly pointed to synthetic compounds in nonstick cookware and waterproof clothing as key contributors to everyday exposure, with one report noting that these toxins are now being linked to weakness, vision changes, and numbness, hallmark symptoms of MS, in a local television segment.

Another account, citing the same research, described how PFAS‑containing products such as nonstick pans and waterproof jackets can shed particles into household dust or leach into drinking water, gradually building up in the bloodstream over years. That report, which framed the work as linking synthetic compounds to a lifelong neurological condition, emphasized that the same symptoms of weakness, vision changes, and numbness are now being tied to these chemicals in a national news story. A separate health piece underscored that PFAS, or per‑ and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are common household chemicals and that they are now being linked to an increased risk of a serious neurological condition, a point that has drawn political attention as well, as noted in a Spanish‑language health report that also referenced RFK and broader concerns about environmental toxins.

Why neurologists are paying attention

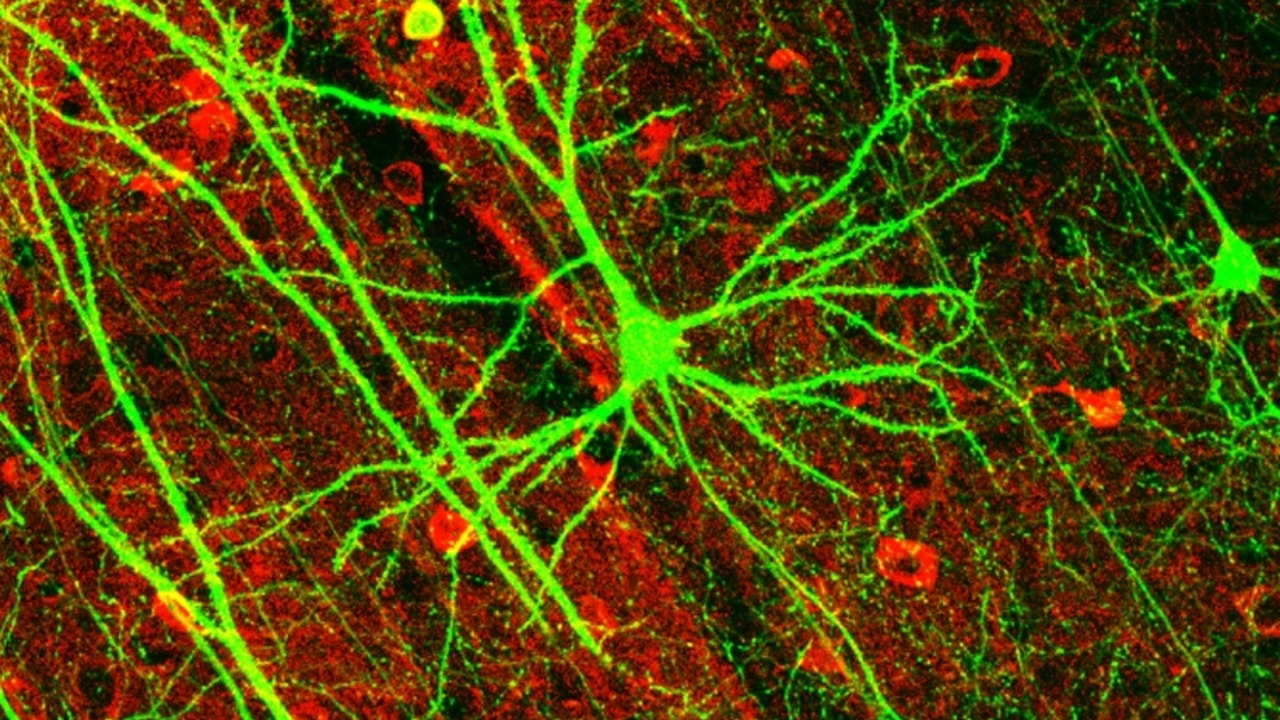

Multiple sclerosis is a complex disease in which the immune system attacks the protective myelin coating around nerve fibers, disrupting signals between the brain and the rest of the body. For years, neurologists have known that genes, particularly certain HLA variants, and lifestyle factors such as smoking and vitamin D levels influence risk. What stands out in the new research is that the associations between PFAS, PCBs, and MS remained even after adjusting for those known influences, suggesting that chemical exposure may be an independent piece of the puzzle, as highlighted in the initial coverage of the study and in a more detailed explanation of how PFAS and PCB interact with immune pathways.

Advocacy groups have quickly picked up on the implications. The Multiple Sclerosis Foundation summarized the work by noting that a new study suggests people who have been exposed to both PFAS and PCBs are more likely to be diagnosed with MS, particularly when exposure is higher, a message that appears in an advocacy briefing. On social media, American Brain Foundation board member Richard Ransohoff, MD, amplified the findings, with one post noting that exposure to certain forever chemicals could increase multiple sclerosis risk and drawing engagement from 56 users, as seen in an Instagram update. That kind of attention from both clinicians and patient communities signals that the study is already influencing how experts talk about environmental risk.

What this means for public health and everyday choices

For regulators and public health officials, the study adds urgency to ongoing debates about how aggressively to restrict PFAS and related chemicals. One detailed news release from Uppsala University stressed that exposure to PFAS and PCBs was linked to higher odds of MS, reinforcing the argument that these compounds should not be treated as benign background pollution, as described in the university communication. A widely shared consumer‑focused story framed the research as evidence that forever chemicals are now tied to another serious health condition, explaining that a new study published in a peer‑reviewed journal found a significant association between PFAS exposure and MS, a message that resonated with readers of a popular magazine and was reiterated in a follow‑up piece that highlighted the NEED and KNOW elements for everyday readers.

More from Morning Overview