Cardiologists have spent decades trying to stabilize the fatty plaques that clog arteries, but a new wave of immunotherapy is going after the diseased cells at the heart of the problem. In mice, an experimental antibody has wiped out harmful artery cells and sharply reduced plaque, hinting at a future in which heart attacks are prevented by precision immune engineering rather than lifelong symptom management. The same logic is now being tested with engineered T cells and nanomedicine, turning atherosclerosis into the next frontier for technologies first honed in cancer.

How a synthetic antibody turns the immune system on artery plaque

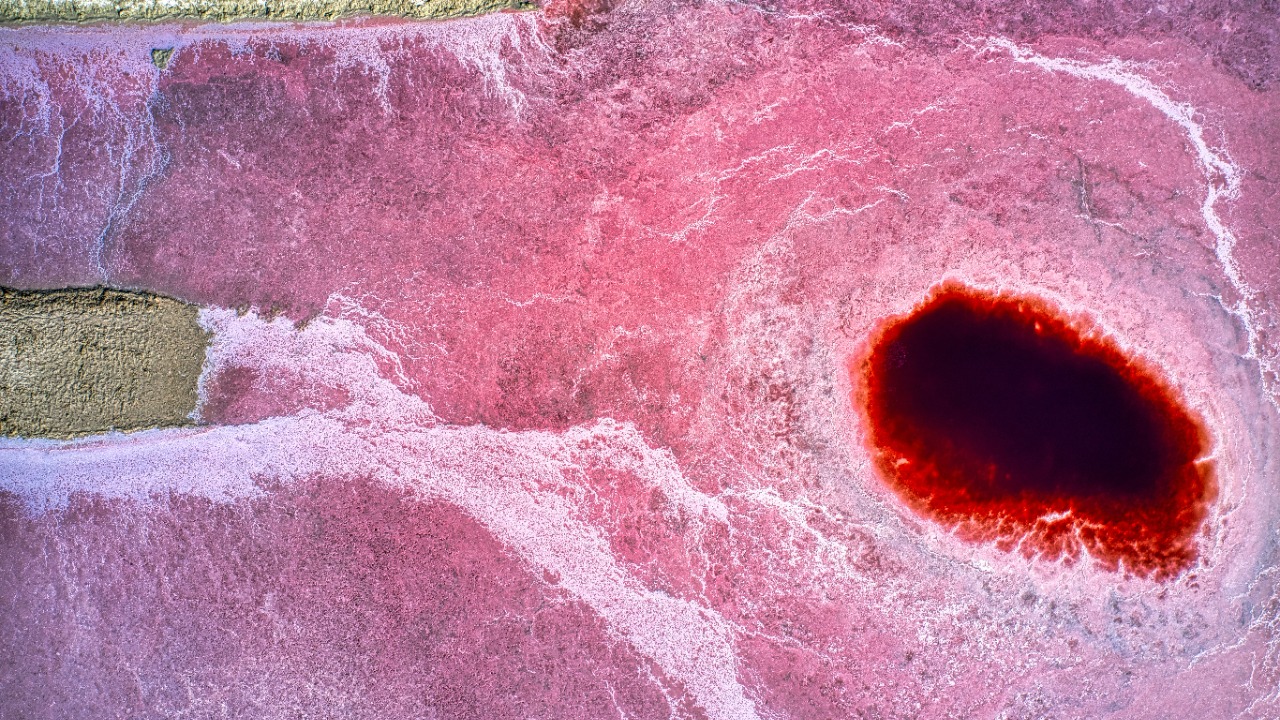

The latest advance centers on a lab built antibody that behaves like a guided missile for rogue cells inside artery walls. In the Science study, researchers designed a synthetic protein that recognizes a specific marker on damaged smooth muscle cells and inflammatory cells that accumulate in atherosclerotic lesions, then flags them for destruction by the body’s own T cells. In mice with established atherosclerosis, this experimental immunotherapy cleared these harmful artery cells and led to a striking reduction in plaque burden, according to detailed imaging and tissue analysis reported through plaque in mice.

The molecule at the center of the work is a bispecific T cell engager, or BiTE, which binds both the target cell in the artery and a passing T cell so the two are forced into contact. By physically bringing these cells together, the BiTE converts diffuse immune surveillance into a focused attack on the diseased patch of vessel wall. Reporting on the same Science paper notes that the therapy uses a synthetic antibody, a type of lab generated protein, to redirect immunity against atherosclerosis, and that the study is formally published in Jan in Science, a detail highlighted in multiple summaries of the arteries of mice.

From BiTE to better healing: what happens inside the artery wall

What makes this approach more than a blunt clean out is the way it appears to reset how the artery heals. By selectively removing the most damaging cells, the BiTE seems to shift the plaque environment away from chronic inflammation and toward a more orderly repair response. One analysis of the Science data describes how eliminating these cells reduced plaque size and altered its composition, with fewer unstable features that are typically linked to rupture, a pattern echoed in coverage that again notes the Jan publication in Science.

One of the investigators captured the mechanism in a single line, saying, “What this BiTE molecule seems to be doing in removing these damaging cells is leading to an improved wound healing process, reducing the size of the plaque and making it more stable,” a description that matches the changes seen in coronary plaques on imaging scans and histology. That quote, reported under the heading What in one industry write up, underscores that the therapy is not just scraping away debris but orchestrating a more favorable remodeling of the vessel wall, a nuance that becomes clear when reading the detailed account of What this BiTE.

CAR T cells push cardiovascular immunotherapy beyond antibodies

The BiTE work is not happening in isolation, and I see it as part of a broader pivot that treats atherosclerosis as an immune disease rather than just a plumbing problem. Earlier preclinical research has already shown that chimeric antigen receptor T cells, or CAR T cells, can be reprogrammed to recognize and attack plaque associated cells in the vasculature. A pioneering study from PHILADELPHIA reported that mice receiving such CAR T cells had about 70 percent less arterial plaque than controls, a dramatic effect that is described in detail in a release on 70 percent.

In that work, the team created Anti inflammatory CAR T cells that home in on atherosclerotic lesions and dampen the signals that keep plaque simmering. The New CAR strategy, developed at a major academic center, is framed as a way to extend cancer style cell therapies to the most common form of heart disease, and the investigators argue that CAR T cell therapy could be a highly effective tool against atherosclerosis if safety and durability hold up in larger models. The concept is laid out in institutional coverage of the new strategy and in a companion explanation that CAR T cell therapy could be a highly effective tool against atherosclerosis.

Nanotherapy shows a parallel path to dissolving plaque

While immune cell engineering grabs headlines, nanomedicine is quietly offering a complementary way to strip plaques of their most dangerous components. In one influential mouse study, researchers used carbon nanotubes to ferry a drug that flips macrophages from a pro inflammatory state into a more reparative mode, specifically within atherosclerotic lesions. That nanotherapy reduced plaque buildup in mouse arteries and helped the immune system clear dying cells in the plaque core, a result described in detail in a report on Nanotherapy.

More recently, a separate nanotherapy platform has been shown to target artery inflammation in cardiovascular disease by loading nanoparticles with agents that reprogram immune cells sitting inside plaques. These treated cells “eat” away parts of the plaque core, removing it from the artery wall and decreasing levels of blood vessel inflammation, a mechanism that could translate into safer, more effective cardiovascular therapies if it scales. The approach is summarized in a technical overview of artery inflammation, and a more public facing demonstration of nanoparticle therapy breaking down arterial plaques and reducing the risk of heart attacks and strokes has circulated widely on nanoparticle therapy.

Why mouse breakthroughs matter, and what still stands in the way

As impressive as these results are, I have to stress that every one of them comes from preclinical models, mostly mice that develop plaque under tightly controlled conditions. The BiTE antibody that cleared harmful artery cells and the CAR T cells that cut plaque by roughly 70 percent have not yet been tested in people, and the immune systems of humans are more complex and less forgiving. The teams behind the BiTE work repeatedly emphasize that the study is published in Jan in Science and that atherosclerosis is an exciting prospect for immunotherapy, language that appears in multiple summaries of the arteries of mice and in a separate notice that immunotherapy cuts artery plaque in mice, but they also acknowledge that safety, dosing, and off target effects must be mapped carefully before any human trial.

There are also practical questions about how to deliver such therapies outside elite research centers. CAR T cell manufacturing is expensive and logistically complex, and even a synthetic antibody like the BiTE will need rigorous testing to ensure it does not trigger unintended immune attacks on healthy tissue. At the same time, the convergence of BiTEs, CAR T cells, and nanotherapy suggests that cardiovascular medicine is entering a phase where directly editing or redirecting the immune system is no longer science fiction. Institutional briefings on the New CAR strategy describe how a pioneering preclinical study has opened the door to applying CAR T cells to common diseases beyond cancer, a point made explicitly in a release on New CAR, while companion coverage reiterates that CAR T cell therapy could be a highly effective tool against atherosclerosis. Against that backdrop, the BiTE study, summarized in multiple places as immunotherapy cutting artery plaque in mice, looks less like an outlier and more like the next logical step in a rapidly evolving field.

More from Morning Overview