More than a century before graphene was isolated in a modern lab, Thomas Edison may have been unknowingly making the wonder material inside his early light bulbs. New experiments suggest that the carbon filaments glowing in his 1879 design could transform into atom-thin carbon sheets under the right conditions. If that interpretation holds, it would mean Edison stumbled onto graphene roughly 130 years before it was officially recognized.

I see this story as more than a historical curiosity. It forces a rethink of how innovation unfolds, showing that even a figure as closely studied as Edison might still be hiding surprises in plain sight. It also hints that some of today’s “cutting edge” materials may have been quietly produced in Victorian workshops, long before anyone had the tools to see what was really happening.

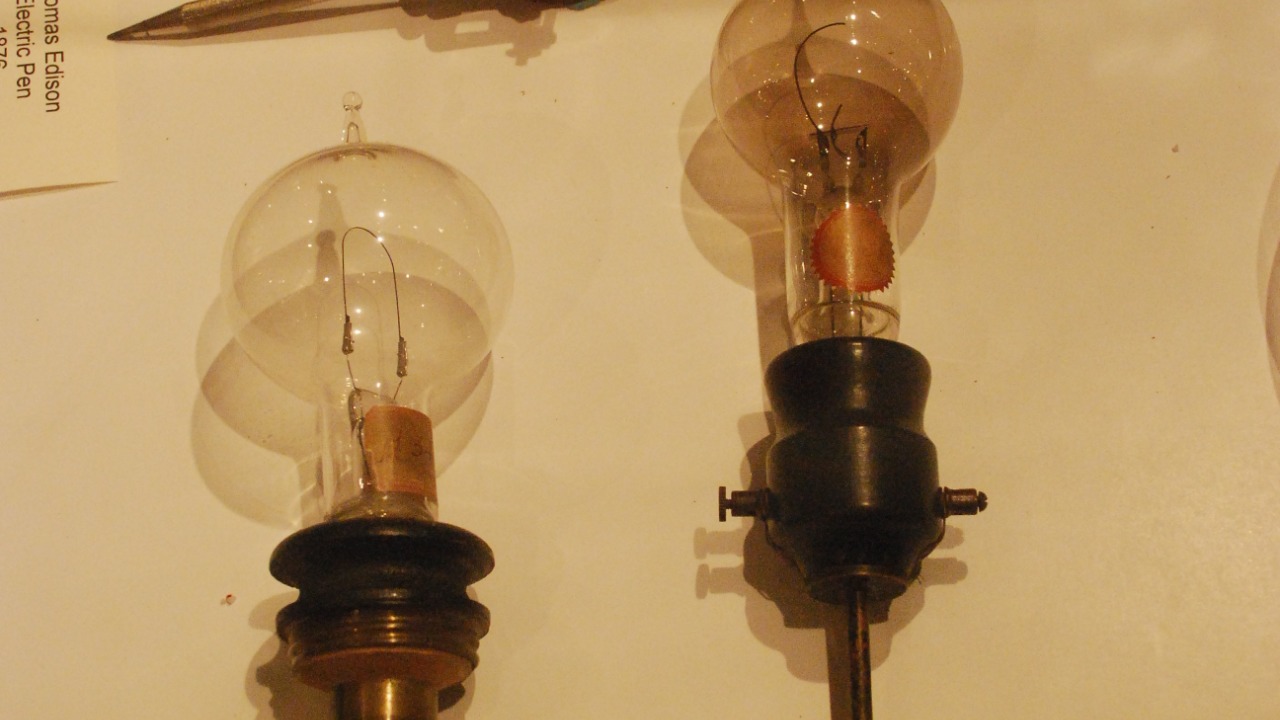

Recreating Edison’s bulb with modern tools

The new work centers on a simple but powerful idea: rebuild Thomas Edison’s 1879 light bulb as faithfully as possible, then examine it with twenty‑first century instruments. Researchers at Rice University set out to reproduce the original carbon filament design, then drove it under operating conditions similar to what Edison used. Instead of treating the bulb as a museum piece, they treated it as an experiment, letting the filament heat, age, and fail while they captured what formed on and around it.

When I look at their approach, what stands out is how they used contemporary analytical tools to interrogate a nineteenth century device. By combining microscopy and spectroscopy on the spent filaments, the team could see atomic‑scale structures that Edison never could. Their analysis points to thin carbon layers arranged in a hexagonal pattern, the hallmark of graphene, emerging from the stressed filament material. In other words, the same basic physics that modern labs exploit to make graphene sheets may have been at work inside Edison’s glass bulbs all along.

How a carbon filament can turn into graphene

To understand why this is plausible, it helps to revisit how those early bulbs were built. Edison’s 1879 design relied on carbonized filaments sealed in a low‑pressure glass envelope, then driven with enough current to glow without immediately burning up. Under that intense heat, carbon atoms can rearrange themselves, especially when the surrounding environment is starved of oxygen. According to Edison focused work, those conditions are ideal for coaxing carbon into a hexagonal honeycomb lattice, the exact structure that defines graphene.

What the recent experiments suggest is that the filament surface does not simply char or crumble as it ages. Instead, parts of it reorganize into layered, sheet‑like structures that match the atomic arrangement of graphene. When I think about the physics, it makes sense: high temperature, limited oxygen, and mechanical stress can all drive carbon toward more stable configurations, and graphene is one of the most stable two‑dimensional forms available. The surprise is not that graphene can form there, but that no one thought to look for it in a device as iconic and well studied as Edison’s bulb.

Evidence that Edison beat graphene’s “discovery” by 130 years

The claim that Edison effectively made graphene long before it had a name rests on both historical and experimental evidence. Historically, his notebooks and patents describe the use of carbon filaments and the operating regimes that would have produced the necessary temperatures inside the bulb. Experimentally, the Rice University team’s reconstructions show that when those same conditions are recreated, graphene‑like layers appear on the filament remnants. One analysis explicitly frames this as Edison having produced graphene more than 130 years before it was officially invented, a striking reframing of the material’s timeline.

From my perspective, the key is not whether Edison consciously “discovered” graphene, but whether his process reliably produced it as a byproduct. Reports describing how Researchers in the US have uncovered evidence of graphene formation in Edison‑style bulbs, using modern analytical tools, make a strong case that the material was present. The fact that it went unrecognized for so long underscores how scientific “firsts” often depend less on when a phenomenon occurs and more on when someone has the conceptual and technical framework to see it.

What this means for Edison’s legacy and materials history

If Edison’s 1879 bulb really was a tiny graphene factory, it subtly shifts how I think about his legacy. He is already credited with turning electric light into a practical technology, but this work hints that his experiments also brushed up against a material that would later earn a Nobel Prize for its modern investigators. Accounts of how Rice University researchers recreated Thomas Edison’s bulb and linked it to graphene formation highlight that he may have been closer to cutting‑edge materials science than anyone realized at the time. It adds a new layer to the familiar story of the Menlo Park inventor tinkering with filaments late into the night.

There is also a broader lesson about how materials history is written. The idea that a Victorian‑era device could generate a material now central to advanced electronics, sensors, and composites shows how often technology outpaces theory. When I see social media posts asking, as one Did Edison themed discussion does, whether Edison accidentally made graphene in 1879, it reflects a growing recognition that the boundaries between past and present innovation are more porous than they look in textbooks.

From carbon filaments to modern superconductors

The graphene angle also connects to a wider reappraisal of carbon‑based components in early electrical technology. I find it telling that some researchers, revisiting the history of light bulbs, have noted how Edison’s breakthrough not only made electric lighting practical but also relied on filaments that were later replaced by tungsten. One analysis points out that Edison’s early lamps commonly incorporated carbon‑based filaments before manufacturers shifted to tungsten filaments in later designs. That transition, driven by durability and efficiency, may have quietly ended an era in which consumer devices were inadvertently producing exotic carbon structures.

Looking ahead, I see a kind of symmetry in how the story is looping back. Modern labs now deliberately engineer graphene and related materials for applications that range from flexible phone screens to experimental superconducting devices. At the same time, contemporary scientists are returning to Edison’s 1879 light bulb as a testbed for understanding how those same materials can emerge under far simpler conditions. The fact that Researchers can now map the hexagonal honeycomb lattice inside a replica of his bulb closes a historical loop, linking the age of carbon filaments to the age of atom‑thin conductors.

More from Morning Overview