Earth’s magnetic north has just crossed an invisible threshold in the Arctic, slipping into a region that modern navigation models have never charted in detail. The shift is subtle on a map but profound for systems that depend on a stable magnetic reference, from smartphone compasses to intercontinental flight paths. I see it as a reminder that the planet’s deep interior is restless, and that our digital infrastructure is now tightly coupled to that hidden motion.

From Boothia Peninsula to a new Arctic frontier

When explorers first went looking for the magnetic pole, they treated it as a fixed prize, not a moving target. Ever since James Clark Ross identified it on the Boothia Peninsula in the 19th century, the assumption was that it would drift slowly, tracing a loose path around Canada. Historical reconstructions show that for more than 400 years the North Magnetic Pole meandered across the Canadian Arctic, close enough to be treated as a familiar neighbor rather than a runaway point.

That long, gentle wander has given way to something more dramatic. Over the past few decades, scientists tracking the North Magnetic Pole have watched it accelerate away from Canada and toward northern Eurasia, a motion that earlier reporting described as “hurtling” toward Siberia at about 34 miles per year. Now, according to researchers who say Earth’s magnetic north has crossed an invisible “border” in the Arctic, the point has slipped into territory that modern observers have never seen it occupy. That crossing is what turns a long running drift into a genuinely new chapter.

A pole that will not sit still

What makes this moment different is not just that the pole has moved, but how it is moving. Earlier analyses warned that Earth‘s Magnetic North Pole Is on the Move, And It Is Not Normal, with the pace of change outstripping what many navigation systems were built to handle. More recent work indicates that Earth‘s magnetic north pole has resumed its shift toward northern Eurasia while simultaneously slowing its pace of advance, a change in behavior that forced an urgent update to the global model used by airplanes, ships, GPS receivers and cell phones. I read that combination of rapid relocation followed by deceleration as a sign that the underlying forces in the core are rebalancing rather than simply racing in one direction.

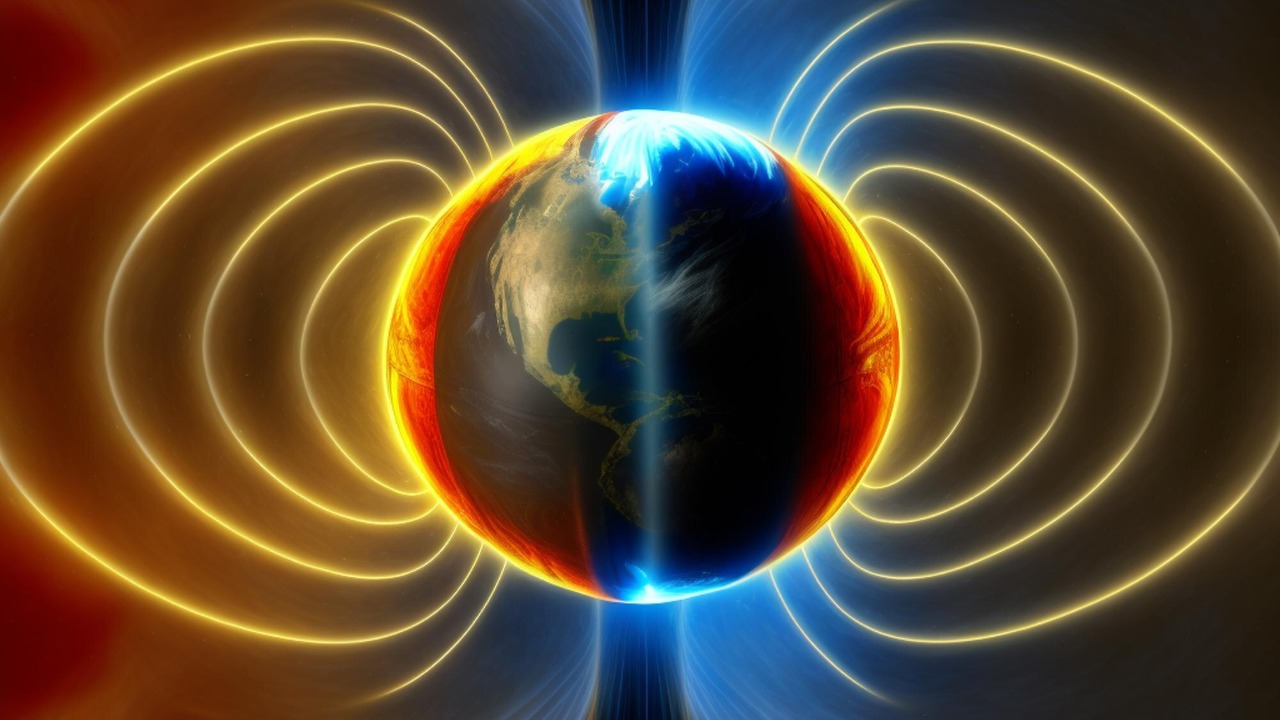

Scientists trying to explain this erratic path are looking deep below our feet. One analysis notes that, According to a report published in Nature, the movement could be linked to hydromagnetic waves rising from deep in the planet’s core, where liquid iron and nickel generate the field. Another video explainer underscores that earth’s north magnetic is on the move and that our technology, from aircraft avionics to smartphone apps, is far more sensitive to that motion than most people realize. The result is a pole that not only refuses to sit still, but also changes speed and direction in ways that challenge long standing assumptions.

The invisible border in the Arctic

Researchers now say They detected that the North Pole has crossed an invisible border in the Arctic, and that the question is no longer whether it is moving but what will happen when the next phase of that motion unfolds. That “border” is not a political line, it is a threshold between regions dominated by different magnetic structures in the core, often described as competing lobes beneath Canada and Siberia. As the pole slides toward the lobe under northern Eurasia, the balance of those deep magnetic influences appears to be shifting, which is why the new position sits in a zone that experts say they have never seen it occupy.

For navigation specialists, that crossing is more than a curiosity. One detailed summary explains that WMM, the World Magnetic Model, had to be sharpened to capture this new configuration, because the pole’s officially shifted position continues its movement away from Canada and toward Siberia. Another account stresses that Experts around the world collaborate every five years to update the World Magnetic Model, or WMM, precisely because this shifting magnetic landscape can push the pole into unfamiliar regions. I see the “never mapped” label less as hyperbole and more as a technical reality: the gridlines that guided navigation for decades simply did not anticipate the pole occupying this patch of Arctic seafloor.

Why the World Magnetic Model had to be rebuilt

Behind the scenes, the quiet hero of this story is the World Magnetic Model itself. Scientists from NOAA and the British Geological Survey have just released an updated World Magnetic Model, or WMM, after using survey data to recalibrate where magnetic north actually sits. Another technical note emphasizes that According to William Brown, a geomagnetism researcher with BGS (British Geological Survey), this upgrade, built on extensive survey methods, primarily benefits systems that rely on precise heading information, from commercial jets to offshore drilling platforms. In my view, the fact that such a model now needs mid cycle corrections underlines how quickly the field is evolving.

The latest version of the WMM goes beyond a routine refresh. A detailed breakdown notes that the World Magnetic Model released in 2025 provides a more precise map of magnetic north, including a higher resolution version with ten times greater detail than previous models, which is vital for navigation on long routes such as a journey from South Africa to the United Kingdom. A separate update from NOAA notes that a Facebook Facebook Screenshot highlights how WMM2025 has already proven to be an accurate model of the Earth’s magnetic field in its first year of operation and that it is embedded in practically every smartphone. When I open a maps app on my own phone and watch the compass snap into place, I am effectively seeing that model at work.

When a wandering pole rewrites navigation

The practical stakes of this Arctic detour show up in cockpits, shipping lanes and even hiking trails. One analysis points out that the magnetic North Pole is on the move again and that this time it is rewriting the rules of navigation, with Scientists from NOAA warning that even small angular errors can add up to tens of kilometers over long distances. Another summary notes that the silent shift in the field has already forced updates to the global model used by airplanes, ships, GPS and cell phones, with the new version promising ten times greater accuracy in oceanic and polar routes. For pilots flying into high latitude airports or icebreakers threading narrow channels, that extra precision is not a luxury, it is a safety margin.

Consumer technology is just as exposed. A European mission notes that Since it was first measured in 1831, we have known that the magnetic north is constantly on the move, However, its recent acceleration prompted ESA’s Swarm satellites to help pinpoint a new magnetic north for smartphones, improving location accuracy for apps that depend on a reliable compass. A separate explainer warns that Magnetic North Pole moving faster than ever and that And It Is Not Normal, raising the prospect that older devices or poorly updated apps could quietly drift out of alignment. When I think about drivers relying on in dash navigation in remote regions, or hikers trusting a phone compass in low visibility, the importance of keeping those digital maps synced to a restless pole becomes very concrete.

More from Morning Overview