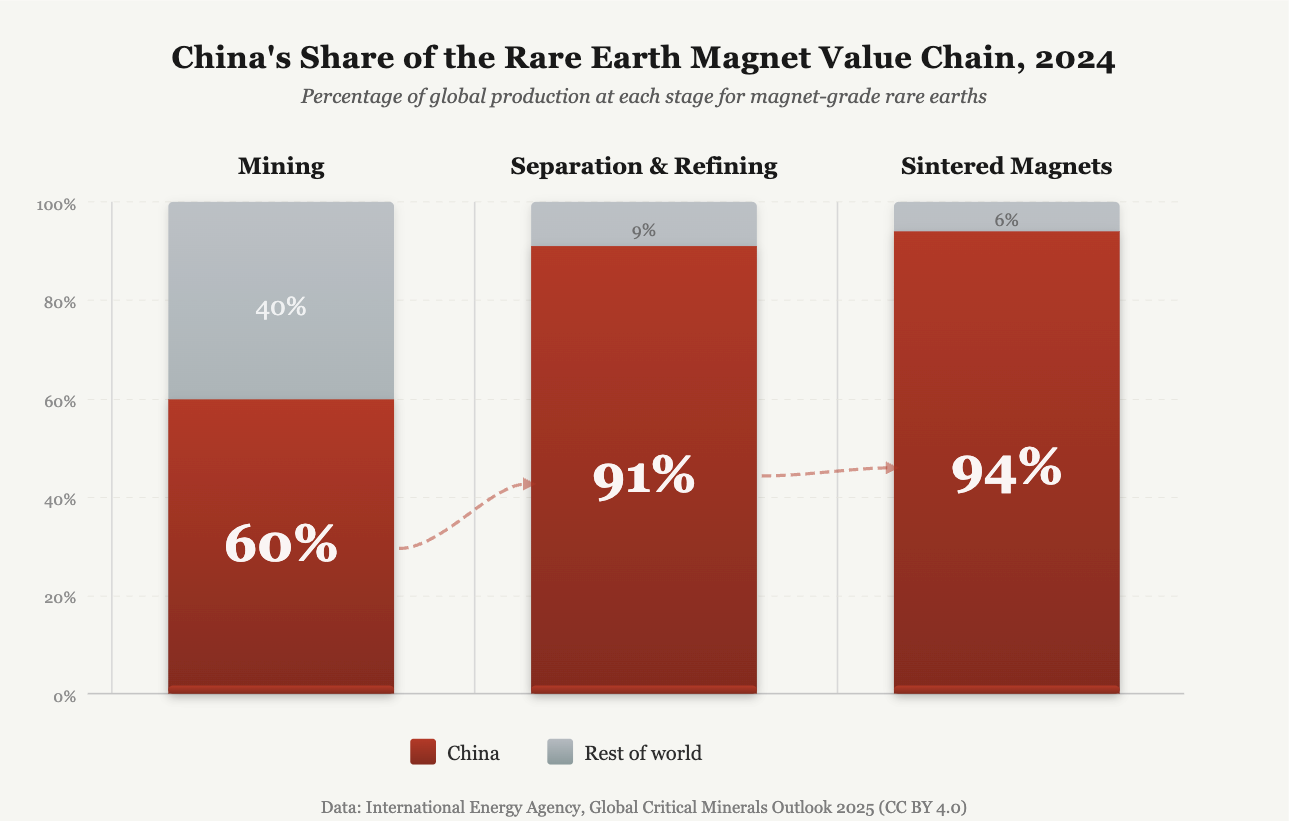

China’s dominance of rare earth processing has quietly become one of the most consequential chokepoints in the global economy. According to the International Energy Agency, China accounts for about 60% of global rare earth mining for the key magnet elements, roughly 91% of refining and separation, and 94% of sintered permanent magnet production, the high-performance magnets that go into electric vehicle motors, wind turbines, missile guidance systems, and AI data center hardware. The U.S. Geological Survey’s 2025 Mineral Commodity Summaries reported that the United States was 80% import-reliant for rare earth compounds and metals in 2024, with China as the leading supplier, accounting for an estimated majority of that consumption when direct and indirect imports are combined.

Western governments are now racing to rebuild capacity. The Trump administration has rolled out a $12 billion strategic mineral stockpile, taken direct equity stakes in miners, and assembled a 54-nation-plus-EU alliance to coordinate supply chains. But the response risks locking in dependence at precisely the moment demand for rare earth magnets is accelerating, driven by the electrification of transport, the buildout of renewable energy, and the explosion of AI infrastructure. The strategic dilemma is simple to state and far harder to solve: the West can mine more ore, but without its own refineries and magnet factories, it still has to send material back through Chinese plants.

How deep the dominance runs

The 17 rare earth elements are not actually rare in the earth’s crust. What is rare is the economic concentration of their processing. The IEA’s Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025 found that geographic concentration in refining has actually worsened: between 2020 and 2024, roughly 90% of supply growth in refined rare earths came from China. For the magnet-grade elements, neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, and terbium, China’s share jumps at each stage of the value chain: about 60% of mining, approximately 91% of separation and refining, and 94% of sintered permanent magnet manufacturing. Two decades ago, China held about 50% of the sintered magnet market.

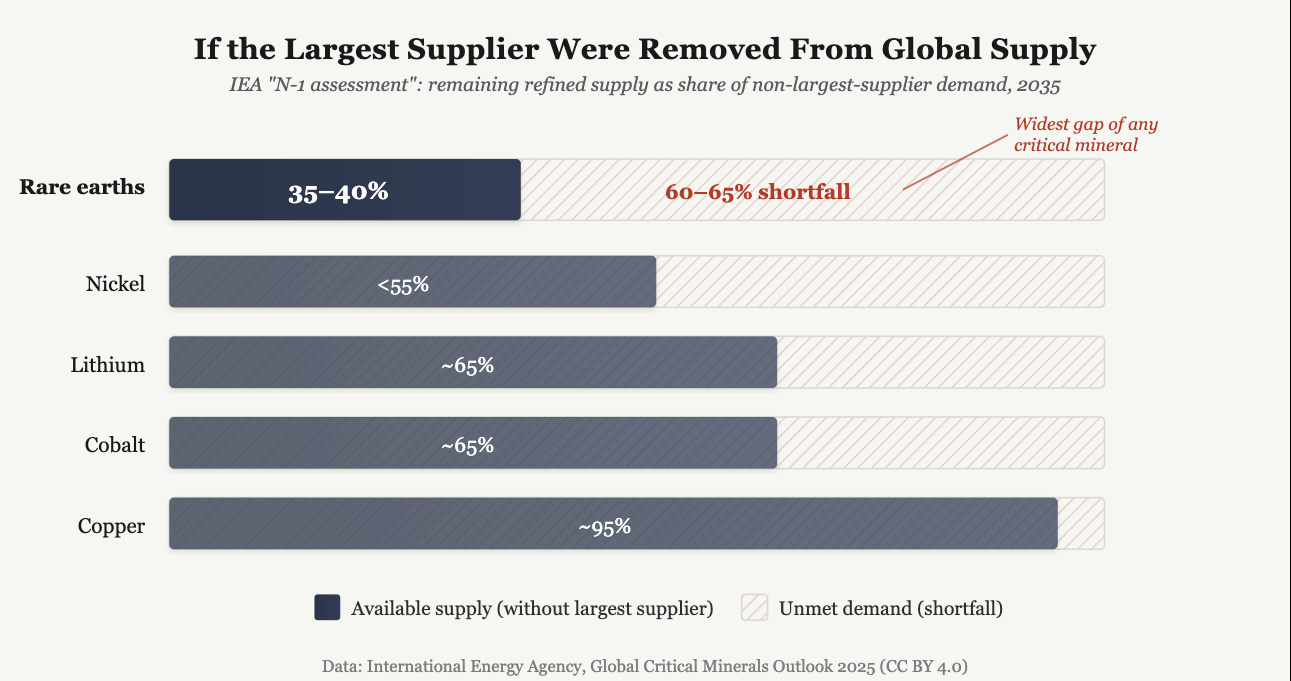

The monopoly is not in the resource itself, China holds about 44 million of the world’s roughly 115 million metric tons of proven reserves, according to the USGS, but in what happens after extraction: the acid leaching, solvent extraction cascades, oxide separation, metallization, and sintering that transform raw ore into the magnets embedded in an F-35’s actuators or a Tesla’s drive motor. Even when new mines open in Australia, Canada, or the United States, they frequently still rely on Chinese separation capacity. By 2035, the IEA projects China will supply around three quarters of refined rare earth elements. If that supply were removed entirely, a scenario the IEA calls an “N-1 assessment”, remaining capacity would cover only 35% to 40% of demand outside China. No other critical mineral shows a gap that wide.

From theoretical risk to active leverage

For years, rare earth concentration was a theoretical concern. That changed in 2025. On April 4, in retaliation for U.S. tariff escalations, China introduced export controls on seven heavy rare earth elements, including dysprosium and terbium. The IEA reported that export volumes dropped sharply, automakers struggled to obtain permanent magnets, and rare earth prices in Europe surged to as much as six times Chinese domestic levels.

On October 9, Beijing escalated further, announcing controls that encompassed processing technologies, equipment, and finished products containing even 0.1% Chinese-origin rare earth content. For the first time, China explicitly banned exports for foreign military end-use, directly targeting the U.S. defense industrial base. A Trump-Xi summit in Busan on October 30 produced a one-year suspension of the October controls. But Bloomberg reported in December 2025 that U.S. buyers were still unable to obtain key materials. Noveon Magnetics CEO Scott Dunn told Bloomberg: “People aren’t getting materials out of China.” And in January 2026, China extended new restrictions to Japan, banning dual-use exports including rare earths to Japanese military end-users and slowing licensing reviews for broader commercial shipments.

“Xi was ready for Trump in his second term and has a powerful weapon in rare earths. China is getting the better of the US in these recent truce negotiations.”

Washington’s response

The Trump administration has responded with arguably the most aggressive U.S. critical minerals policy in decades. The centerpiece is MP Materials, which operates the Mountain Pass mine in California. In July 2025, the Department of Defense struck a deal that included a $400 million equity stake, a guaranteed price floor for neodymium-praseodymium, a $150 million loan for heavy rare earth separation, and a commitment to purchase 100% of the magnets from a planned new facility. MP’s Fort Worth plant began commercial NdPr metal production in early 2025, with heavy rare earth separation at Mountain Pass expected by mid-2026.

The scale gap remains enormous. MP’s planned 1,000 metric tons of annual magnet output is less than 1% of China’s estimated production of over 130,000 metric tons. The administration has also taken equity stakes in USA Rare Earth, Lithium Americas, and Trilogy Metals, and backed a $1.6 billion investment in USA Rare Earth’s magnet facilities, targeted for 2028. On February 2, 2026, the president unveiled Project Vault, a $12 billion strategic mineral reserve combining a $10 billion Export-Import Bank loan with nearly $2 billion in private capital. The stockpile buys time, but as Fortune noted, it is a “first step of many.”

Internationally, Secretary of State Marco Rubio hosted the 2026 Critical Minerals Ministerial on February 4, announcing FORGE, the Forum on Resource Geostrategic Engagement, as a successor to the Biden-era Minerals Security Partnership. FORGE will establish reference prices at each production stage, enforced by tariffs to maintain a floor within the allied trade zone. The explicit target is China’s strategy of flooding markets with subsidized minerals to bankrupt emerging Western projects. Eleven countries signed bilateral agreements at the ministerial, with 17 more in negotiation.

The clock problem

Across all of these initiatives, the fundamental constraint is time. Building a mine takes 7 to 15 years. Building refining capacity requires mastering solvent extraction processes and operating them reliably at scale. And building magnet manufacturing at scale requires downstream demand, which the administration has complicated by cutting incentives for the electric vehicles and wind turbines that consume the majority of rare earth magnets, as PBS reported.

MP Materials produced a record 45,000 metric tons of rare earth oxides at Mountain Pass in 2024, but ceased concentrate sales to China only in July 2025, meaning America’s flagship mine was shipping output to the very country the policy is designed to counter. Meanwhile, China is not standing still. The IEA notes that China’s share of magnet manufacturing remains near total in the segments that matter most for EVs, wind, and defense supply chains. Beijing has also extended its regulatory reach extraterritorially: from December 2025, its controls apply to internationally manufactured goods containing Chinese-sourced rare earths. As the European Parliament noted, over 80% of large European firms are no more than three intermediaries away from a Chinese rare earth producer.

China’s rare earth leverage was four decades in the making. It will not be undone in four years. But the window to build a credible alternative is open and narrowing. If the West fails to convert its equity stakes, stockpiles, and ministerial communiqués into operating refineries and magnet factories within the next five years, Beijing’s processing monopoly will harden from a political vulnerability into a permanent structural feature of the global economy, and with it, the ability of democratic nations to build their own defense systems, power their own energy transitions, and develop their own AI infrastructure without relying on a geopolitical rival.