A vast, complex sunspot comparable in scale to the region that powered the historic Carrington storm is now rotating across the center of the solar disk, squarely aligned with Earth. Its position means that any major eruption from this active region in the coming days would have a direct path toward our planet, raising the stakes for satellites, power grids, and communications systems that are already under strain from an energetic solar cycle.

Scientists stress that alignment alone does not guarantee a catastrophe, but the combination of size, magnetic complexity, and Earth-facing geometry is exactly what space-weather forecasters watch most closely. As I weigh the latest measurements and historical context, the picture that emerges is not one of inevitable disaster, but of elevated risk that demands attention from policymakers, infrastructure operators, and anyone whose daily life depends on GPS, aviation, or the global internet.

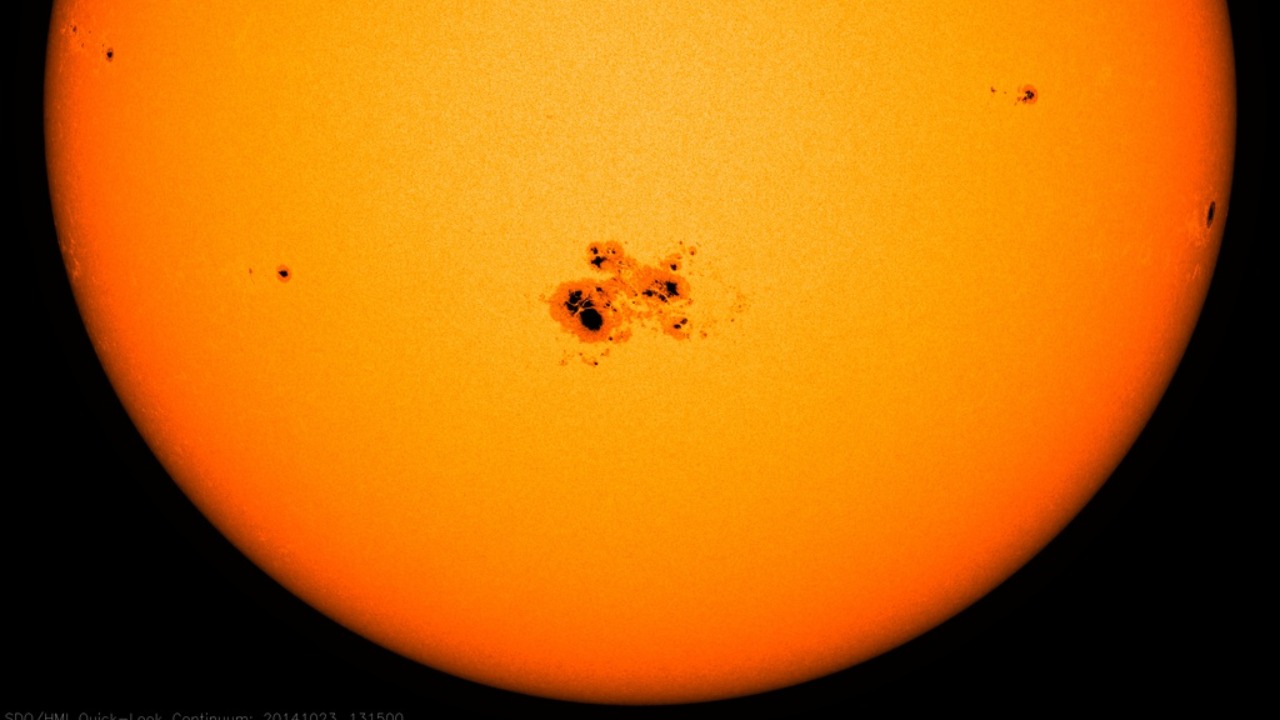

How big this sunspot really is

To understand why this active region is drawing so much scrutiny, I start with its sheer scale. Earlier in the current solar cycle, observers tracked a giant region labeled Sunspot R3664 that stretched across nearly 124,300 miles, 200,000 kilometers, almost matching the dimensions of the legendary Carrington-era spot. The new Earth-facing behemoth sits in that same league, with dark umbrae and lighter penumbrae sprawling across a significant fraction of the visible solar hemisphere, large enough to swallow multiple Earths side by side.

Size alone does not make a sunspot dangerous, but it does set the stage for powerful eruptions when tangled magnetic fields snap and reconnect. Reporting on the current region notes that its dark spots cover an area of the solar surface around 90% the size of the Carrington sunspot, a comparison that immediately places it in the top tier of recorded active regions. When I look at that figure in the context of past storms, it is clear that we are not dealing with a routine blemish on the solar surface, but with a structure that has the capacity to reshape near-Earth space for days at a time.

Why scientists compare it to the Carrington Event

The Carrington benchmark matters because it remains the most intense geomagnetic storm in the instrumental record, a natural yardstick for worst-case scenarios. In 1859, astronomer Richard Carrington sketched a massive sunspot group that unleashed a flare and associated coronal mass ejection, or CME, that slammed into Earth and triggered auroras at tropical latitudes while overloading telegraph systems. Modern analyses describe that storm as a “Carrington-class” solar superstorm, and researchers note that a similar CME passed through Earth’s orbit on 23 July 2012 but missed our planet, a near miss that is documented in detailed reconstructions of the Carrington Event.

When experts say the current sunspot is “on par” with the one Carrington drew, they are not claiming that a repeat of 1859 is guaranteed, only that the physical ingredients are uncomfortably similar. Dec specialists who track solar activity emphasize that a region of this scale and complexity could, under the right magnetic conditions, launch a CME with comparable energy, and they warn that such a blast would not just light up the sky but could also disrupt modern infrastructure in ways that nineteenth century telegraph operators could scarcely imagine. That is why the phrase “Carrington-class” has migrated from historical footnote to active part of today’s risk vocabulary.

What an Earth-facing alignment changes

Alignment is the multiplier that turns a large but harmless sunspot into a genuine hazard. When an active region sits near the center of the solar disk as seen from Earth, any flare or CME it produces is more likely to be directed along the Sun–Earth line, rather than skimming harmlessly off to the side. In the current case, observers note that the giant region has rotated into a position where it is effectively staring straight at our planet, a geometry that maximizes the chance that eruptive material will intersect Earth’s orbit before the spot drifts toward the Sun’s western limb.

However, the story is more nuanced than a simple bullseye. Dec analysts point out that even with a direct line of sight, the magnetic orientation of an ejected cloud determines how strongly it couples with Earth’s field, and not every eruption from a central sunspot produces a severe storm. One detailed assessment notes that, However, in reality, the present region’s dark spots cover an area of the solar surface around 90% the size of the Carrington sunspot, yet the authors still judge a true Carrington Event in the immediate future to be unlikely, even as they warn that a major storm would still be capable of widespread disruption according to Experts.

How flares and CMEs from this region could hit us

From a practical standpoint, what matters now is not just the spot’s size and position, but how it behaves over the next several days. Large, magnetically complex regions tend to produce frequent solar flares, sudden bursts of radiation that can affect radio communications on the dayside of Earth within minutes. More consequential still are CMEs, the vast clouds of charged particles and embedded magnetic fields that can take one to three days to arrive. Analyses of recent activity from similarly complex regions describe “mixed-up” magnetic structures that have already emitted powerful flares, a pattern that often precedes significant CMEs as documented in reports on a mixed-up sunspot.

CMEs typically emit billions of tons of stellar material at speeds of hundreds of miles a second, and when such a cloud is launched from an Earth-facing region, it can envelop the planet in a shock front that compresses the magnetosphere and injects energy into the upper atmosphere. That is why forecasters are watching this Carrington-class spot for signs of large, fast CMEs that could drive geomagnetic storms. The combination of high mass, high speed, and favorable magnetic orientation is what turns a spectacular solar eruption into a ground-level problem for transformers, pipelines, and long-distance power lines.

What official space-weather monitors are seeing

To track that evolving threat, I look first to the official space-weather agencies that monitor the Sun in real time. The Space Weather Prediction Center operated by NOAA provides continuous updates on solar flares, CMEs, and geomagnetic indices, along with alerts for radio blackouts and radiation storms that can affect aviation and satellite operations. Its dashboards and forecasts are the primary tools grid operators and satellite controllers use to gauge whether a particular eruption from this giant sunspot is likely to trigger a minor disturbance or a severe storm, and those products are available to the public through the agency’s main NOAA portal.

Alongside those official bulletins, a network of independent observers and researchers compiles imagery, magnetograms, and aurora forecasts that help translate raw data into intuitive pictures of what is happening on the Sun. One long-running hub for this community aggregates coronagraph movies, solar wind plots, and ground magnetometer traces, and it has already highlighted the current region’s Earth-facing transit and flare potential for a broad audience of enthusiasts and professionals. For readers who want to follow the day-to-day evolution of this Carrington-class spot, that site’s continuously updated space weather coverage is an indispensable complement to the more formal alerts.

Evidence that Earth’s upper atmosphere is already heating up

Even before a truly extreme storm arrives, Earth’s upper atmosphere is responding to the cumulative effect of repeated solar eruptions in this active phase of the cycle. Researchers report that Earth’s thermosphere recently hit a near 20-year temperature peak after soaking up energy from geomagnetic storms that bashed Earth earlier in the year, a sign that the system is already primed with extra heat and density. That finding, documented in a detailed analysis of how Earth responded to recent storms, underscores that the current Carrington-class sunspot is emerging against a backdrop of elevated atmospheric activity rather than a quiet baseline.

That matters because a hotter, denser thermosphere increases drag on satellites in low Earth orbit, from Starlink constellations to Earth-observing platforms, and it can accelerate orbital decay when a strong geomagnetic storm arrives on top of an already expanded atmosphere. The same study notes that Eart orbiting spacecraft have already experienced measurable effects from this heightened state, and another major storm from the present sunspot could amplify those trends. In practical terms, operators may need to perform more frequent orbit-raising maneuvers, and debris-tracking networks will have to account for changing drag conditions as they predict conjunctions and collision risks.

What a Carrington-class hit would do to power and communications

When experts model a direct hit from a storm on the scale of 1859, the most sobering projections involve the electrical grid. Dec analyses of the current sunspot warn that a truly extreme event would wreak havoc on the ground, potentially damaging parts of the electrical grid and forcing prolonged blackouts in regions where transformers are exposed to strong geomagnetically induced currents. Those currents arise when rapid changes in Earth’s magnetic field induce voltages in long conductors, and in a modern grid that means high-voltage transmission lines and the massive transformers that connect them, a vulnerability highlighted by Dec modeling of worst-case scenarios.

Communications and navigation systems would also be in the crosshairs. High-frequency radio links used by transoceanic flights can fade or fail during strong flares, while geomagnetic storms distort the ionosphere that GPS and other satellite navigation systems rely on, degrading accuracy or causing brief outages. Technical assessments of past interplanetary shocks that passed Earth describe how sudden compressions of the magnetosphere can trigger rapid changes in ground magnetic fields, and they point professionals to specialized Technical resources that translate those measurements into actionable risk levels for power systems and pipelines. In a Carrington-class scenario, those same mechanisms would operate at far higher intensities, stressing equipment that was never designed with such extremes in mind.

How GPS, aviation, and everyday tech would feel the storm

For most people, the first sign of a major solar storm would not be a transformer failure, but glitches in the technologies they use every day. Precision agriculture, ride-hailing apps, and smartphone maps all depend on satellite navigation signals that pass through the ionosphere, a region that becomes turbulent and irregular during geomagnetic storms. Specialists who study “signals, scintillation and the solar effect” note that ionospheric disturbances can cause rapid fluctuations in signal amplitude and phase, degrading positioning accuracy and, in severe cases, leading to temporary loss of lock on satellites, a problem that has prompted the development of Various monitoring tools for professionals.

Aviation would feel the impact as well. Airlines that operate polar routes rely on high-frequency radio for communication, a band that is particularly vulnerable to solar flares and energetic particle events. During strong storms, carriers may reroute flights away from high latitudes, increasing fuel burn and travel times, while air traffic controllers adjust procedures to account for degraded radar and navigation performance. Even consumer technologies like satellite internet terminals and satellite phones can experience reduced throughput or brief outages as the storm perturbs the space environment they depend on, a reminder that the invisible infrastructure behind everyday connectivity is tightly coupled to the Sun’s moods.

Why this is a warning, not a prophecy

As dramatic as the phrase “Carrington-class sunspot” sounds, I find it important to separate what the data actually show from the more speculative scenarios that often dominate social media. The measurements are clear that the current region is enormous, magnetically active, and now directly facing Earth, and history tells us that such configurations have produced some of the most powerful storms on record. At the same time, detailed analyses of the present cycle stress that a true repeat of 1859 remains a low-probability event, even with a spot that covers around 90% of the Carrington area, and that most eruptions will fall into the category of manageable, if disruptive, storms rather than civilization-altering catastrophes.

In that sense, I see this moment less as a countdown to disaster and more as a stress test of how well modern societies have learned the lessons of past near misses. The 23 July 2012 CME that missed Earth, the recent heating of the thermosphere, and the growing reliance on GPS and satellite infrastructure all point in the same direction: the stakes are higher than they were in Carrington’s time, but so are our tools for monitoring and mitigation. Whether this particular sunspot delivers a glancing blow or a major storm, the real measure of preparedness will be how quickly grid operators, satellite controllers, and policymakers translate today’s warnings into concrete resilience before the next Carrington-class region swings into view.

More from MorningOverview