The idea that reality might be a kind of cosmic software has shifted from late-night dorm debate to a live question in physics and philosophy. A growing body of work now treats the “simulation hypothesis” as something that can be tested, not just imagined, even as other researchers argue that the universe could never run on any conceivable computer. I find the result unsettling: the more scientists probe the foundations of physics, the more our world starts to look like code, yet the same research also exposes hard limits on that analogy.

At stake is not just whether we are digital ghosts in someone else’s machine, but how far mathematics and computation can really explain the universe. From gravity and quantum mechanics to the behavior of viruses, recent studies are reframing the question from “Is it true?” to “How would we even know?”

Why some physicists say the universe behaves like code

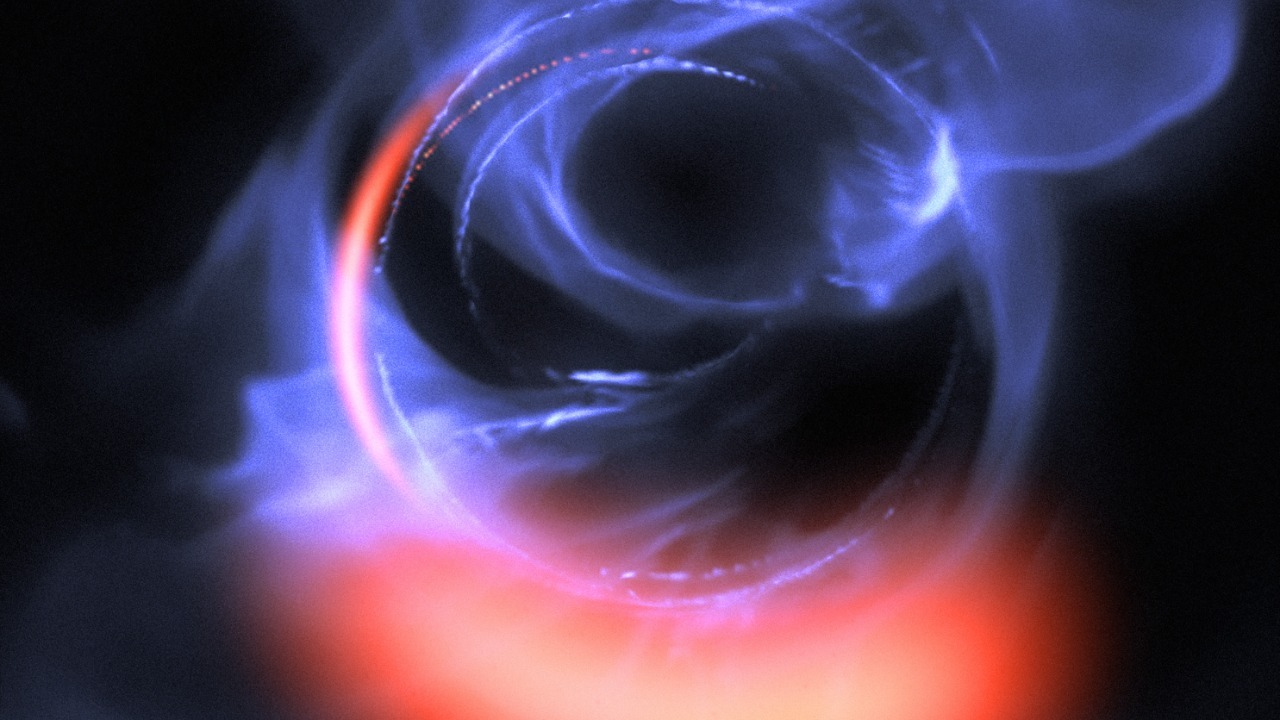

One camp of researchers argues that the fabric of reality already looks suspiciously like information processing. A documentary described in Scribal Multiverse pushes this to its logical extreme, claiming that matter and ideas are the results of a complex digital simulation, with everything we experience as “real” being expressions of a hidden source code. Philosophers have tried to quantify that intuition, with one analysis in Oct arguing that, under certain assumptions about advanced civilizations, the probability we inhabit a simulation is “close to one.” That argument, which Elon Musk has publicly endorsed, was sharpened by a paper described in Dec, which suggested that if technologically mature societies run vast numbers of simulated minds, basic statistics would make our own world more likely to be one of those copies than the original.

Others are trying to move beyond probability arguments and look for physical fingerprints of computation. British physicist Melvin Vopson has proposed that gravity itself might be a clue, suggesting that gravitational attraction reduces information entropy, as if the universe were constantly compressing data to keep a vast program running efficiently. In a related line of work, a physicist studying mutations of the SARS-CoV-2 virus reported hints of a “second law of infodynamics,” a proposed rule in which different information systems, from genomes to digital files, tend to minimize information over time. Coverage of that work, including a piece on a new law of physics, framed this convergence as eerily similar to how a well designed computer system optimizes storage and processing.

Gravity, quantum weirdness and the hunt for “glitches”

Vopson has gone further, arguing that our universe likely functions like a computer simulation and that gravity may be the telltale evidence. In a video shared in Jun, he describes the cosmos as an information processing system, while a separate university release in Apr explains his view of gravity as a new way to think about how the universe stays organized, from galaxies down to every particle inside a single cell. Popular coverage of his ideas, including a feature introduced by PopMech Editors, has leaned into the provocative claim that “Living Simulation Scientist Argues Gravity May Be the Telltale Evidence,” presenting gravity as the background process that keeps the simulation running smoothly. Another report in Apr quoted his description of gravitational pull as an example of data compression and computational optimization in a given space, casting everyday phenomena like objects being pulled together as side effects of information management.

Quantum mechanics adds another layer of strangeness that some see as simulation friendly. A blog from the Palo Alto City Library, titled “Life is a Lie and Here’s Why,” notes that quantum theory says particles in determined states, such as specific locations, do not seem to exist until they are observed, and likens this to needing an observer or programmer for things to happen. A Dec proposal suggested that carefully designed quantum experiments might reveal whether unobserved particles behave as if they are being “rendered” on demand, in the same way a video game only draws the parts of a world the player can see. If such tests ever found a hard limit or pattern that could not be explained by standard physics, it would look uncomfortably like a glitch.

The backlash: hard limits on cosmic computing

For every scientist leaning into the Matrix metaphor, others are pushing back with equally rigorous arguments that the universe cannot be a computer at all. Researchers at UBC Okanagan used detailed simulation models to test whether known physical laws could be reproduced inside a discrete computational grid. Their conclusion, expanded in a technical report highlighted by Nov, was blunt: if the underlying rules of the Platonic realm seem similar to those governing a computer simulation, that realm itself still cannot be a simulation, regardless of how much computing power an advanced civilization might have. A separate roundup of expert views in Nov echoed that skepticism, noting that some Scientists argue quantum gravity theory shows we cannot understand reality through computations alone.

More from Morning Overview