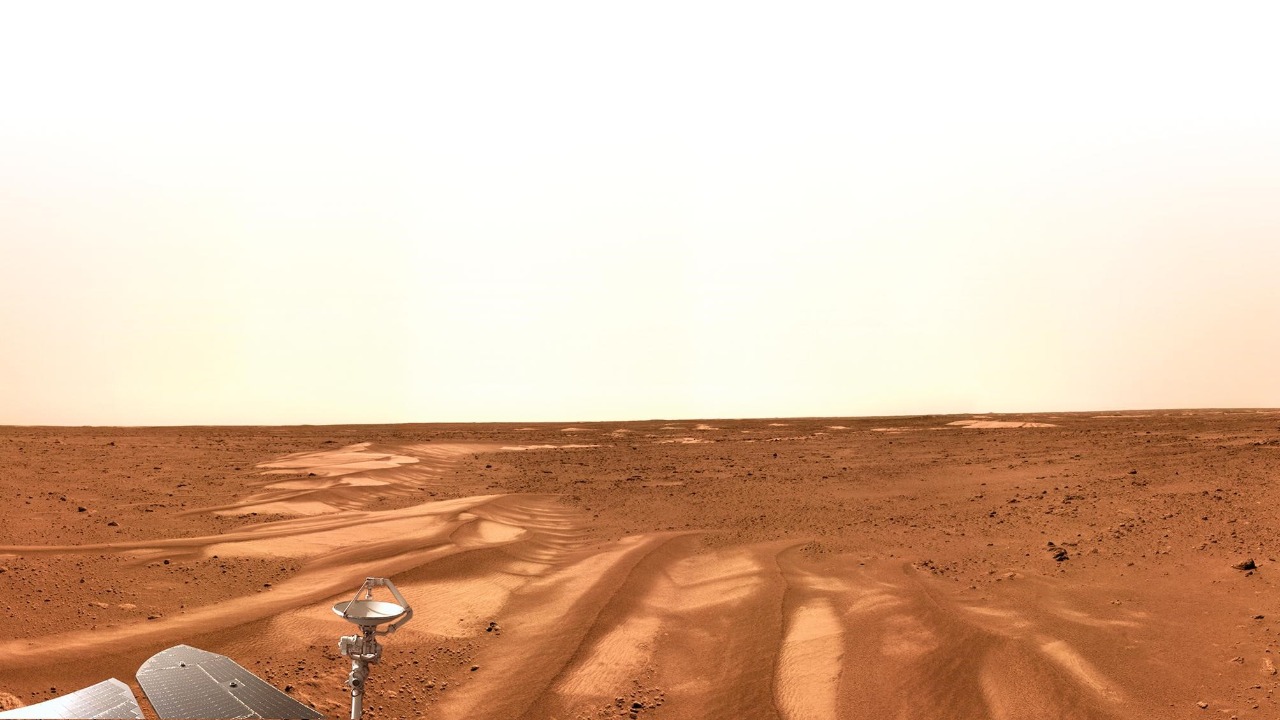

Ancient Mars is starting to look less like a scattered patchwork of dried-up valleys and more like a planet once ruled by continent-scale rivers. For the first time, scientists have traced giant watersheds across the Martian surface, revealing a network of mega basins that once gathered and moved water over thousands of kilometers. The new mapping does not just redraw old channels, it reframes where the planet could have been most habitable and how long liquid water may have persisted.

By treating Mars the way hydrologists treat Earth, researchers have stitched isolated clues into a coherent drainage map that spans entire hemispheres. The result is a set of large river systems that behaved less like brief floods and more like enduring landscapes, with long flow paths that would have maximized contact between water, rock, and potential life.

From scattered valleys to a planet-wide drainage map

For decades, orbital images showed Mars pocked with valley networks and outflow channels, but those features were usually studied in isolation, as if each canyon told its own small story. The new work flips that perspective by asking how those valleys connect, which direction they once drained, and what larger basins they fed. In effect, scientists have taken a planet that looked like a broken puzzle and snapped the pieces into a set of integrated river systems that can be analyzed as wholes rather than fragments.

To do that, researchers used global topography and high-resolution imagery to identify continuous flow paths that link small tributaries into mega watersheds. The resulting map, described as the first comprehensive identification of Martian river basins, shows that many of the classic valley networks are not random scars but parts of 16 large-scale drainage systems that once organized surface water across wide swaths of the planet. That shift, from local landforms to global hydrology, is what finally lets me talk about “ancient Mars’ giant watersheds” as real, mappable entities rather than speculative sketches.

How scientists traced Mars’ ancient mega watersheds

Reconstructing these basins required treating Mars like a digital landscape that could be flooded, drained, and measured inside a computer. Researchers started with elevation models to determine where water would naturally flow under gravity, then traced those paths across the planet to find the lowest outlets and the divides that separate one catchment from another. By following the topographic gradients, they could infer which valleys once belonged to the same system, even when erosion or later impacts had blurred the original channels.

Once those flow paths were mapped, the team could calculate the size and geometry of each watershed, including the length of the main river courses and the total area that would have contributed runoff. That analysis revealed a set of ancient mega watersheds whose scale rivals major terrestrial basins, with some systems stretching across entire regions and converging on low-lying plains or impact basins. The work, described as tracing “ancient mega watersheds on Mars” to identify large river systems and determine their size, shows that the planet’s hydrology was not just local rainfall carving hillsides but a coordinated network of drainage that once tied distant terrains together in a single water story, a result highlighted in ancient mega watersheds.

Sixteen large river basins and the new Martian geography

The most striking outcome of this mapping is the identification of 16 large-scale river basins that once structured the Martian surface. Instead of a chaotic landscape of disconnected gullies, Mars now appears divided into a finite set of drainage domains, each with its own headwaters, trunk rivers, and terminal sinks. These 16 basins define where water collected, how it moved, and where it ultimately pooled, giving planetary scientists a new geographic framework that is as fundamental as the division of Earth into the Amazon, Nile, Mississippi, and other great systems.

Within this framework, each basin becomes a natural laboratory for reconstructing climate and geology. Some catchments gather water from highland terrains and funnel it toward low-lying plains, while others drain into impact basins that may once have hosted deep lakes or even inland seas. The identification of these Martian river basins, described as outlining 16 large-scale systems where life would have been most likely to thrive, turns what used to be a catalog of interesting valleys into a structured map of potential habitats, a shift captured in the identification of Martian basins.

Idae and the complexity of Martian valley networks

Among the mapped regions, the area around Idae stands out as a showcase of how intricate these ancient systems could be. The valley network near Idae is described as complex, with branching tributaries and interwoven channels that resemble the dendritic patterns carved by long-lived rivers on Earth. Instead of a single catastrophic outflow, the landscape suggests repeated or sustained episodes of surface runoff that sculpted a mature drainage architecture.

That complexity matters because it points to a climate capable of supporting extended hydrologic cycles rather than brief, isolated bursts of melting. In the Idae region, the convergence of multiple tributaries into a coherent network implies rainfall or snowmelt feeding streams over significant periods, which in turn would have allowed soils, rocks, and any potential microbes to interact with flowing water again and again. The description of a “complex valley network near Idae” in the new mapping underscores how some Martian basins were not just large but also internally sophisticated, a detail highlighted in the work on Large River drainage systems.

Why long flow paths matter for potential life

From a habitability standpoint, the length of these reconstructed rivers may be as important as their width or discharge. Longer flow paths mean water spends more time traveling across the surface, encountering different rock types, minerals, and temperature regimes. Each kilometer of additional channel is another opportunity for chemical reactions that can concentrate nutrients, alter pH, and build up the gradients that microbes on Earth exploit for energy.

One of the scientists involved in the watershed work noted that longer flow paths increase opportunities for chemical reactions between water and rock, which could enhance the chances for life to emerge or persist. On Earth, river systems like the Amazon or Ganges are not just conduits, they are reactors that transform dissolved elements and organic matter along their course. By revealing that Mars once hosted similarly extended systems, the new mapping suggests that some Martian basins may have been especially favorable for prebiotic chemistry or early biology, a point emphasized in the report that longer flow paths “increase opportunities for chemical reactions between water and rock,” as described in the analysis of longer flow paths.

Rewriting the story of Martian climate and water

These mega watersheds also sharpen the debate over how warm and wet early Mars really was. If the planet supported 16 large river basins with complex valley networks and long flow paths, then its climate must have allowed liquid water to persist on the surface for extended intervals, at least in certain regions. That scenario is harder to reconcile with models that picture Mars as mostly frozen with only rare, short-lived melting events, and it nudges the conversation toward climates that could sustain repeated runoff, perhaps through thicker atmospheres, episodic volcanism, or orbital cycles that favored warmer conditions.

At the same time, the mapped basins provide constraints that climate models must now match. Any proposed atmospheric history for Mars has to be capable of producing enough precipitation or meltwater to carve the observed drainage areas and maintain flow along their reconstructed paths. The fact that scientists can now point to specific basins, with defined sizes and outlets, gives modelers concrete targets rather than vague impressions of “wetness.” The new drainage map, which treats Mars as a planet with large river systems rather than isolated channels, effectively turns climate hypotheses into testable predictions about where water should have flowed and how those flows would have shaped the terrain, as reflected in the detailed mapping of large river drainage systems.

Targeting the best places to search for past life

For mission planners, the most immediate payoff of this work is a sharper map of where to look for biosignatures. Not all ancient water environments are equally promising, and the 16 large basins give a ranked list of places where conditions may have been especially favorable. Basins with long flow paths, complex tributary networks, and terminal lakes or deltas are prime candidates, because they combine sustained water, sediment deposition, and chemical gradients in one package.

The new mapping explicitly highlights that these large-scale river basins are where life would have been most likely to thrive on Mars, turning them into natural targets for rovers, landers, and eventually sample return missions. Instead of choosing landing sites based only on local geology or engineering constraints, mission designers can now ask how a candidate site fits into a broader watershed, whether it sits near a former river mouth, or whether it lies along a trunk channel that would have concentrated organic material. The identification of these basins, described as outlining 16 large-scale systems where life would have been most likely to thrive, gives exploration a hydrologic roadmap that did not exist before, a point underscored in the report that “they outlined 16 large-scale river basins where life would have been most” likely to persist, as noted in the description that They outlined those basins.

What this means for future human exploration

Even though these rivers have been dry for billions of years, their ghostly outlines still matter for future astronauts. Ancient basins can guide where to search for buried ice, hydrated minerals, and sedimentary rocks that might preserve organic molecules. Long trunk valleys could mark corridors where subsurface aquifers once flowed, leaving behind mineral deposits that are easier to mine or study. For human missions that will rely on in situ resources, knowing the structure of past watersheds is a practical advantage, not just a scientific curiosity.

There is also a psychological dimension to walking in the footprints of vanished rivers. Standing in a dry channel that once carried water across half a planet would give crews a visceral sense of Mars as a world that changed, not a static desert. That narrative, of a planet that once had large river drainage systems and complex valley networks like the one near Idae, can help sustain public interest and political support for long-term exploration. The idea that scientists have now mapped those systems for the first time, including the complex valley network near Idae and the 16 large-scale basins where life might have thrived, gives future explorers a story to inhabit, as captured in the description of how Scientists Map Mars’ ancient drainage.

A new baseline for reading Mars’ deep past

With these mega watersheds now charted, every future discovery on Mars can be placed in a clearer context. A clay-rich outcrop is no longer just a patch of altered rock, it is a point along a former river course or within a specific basin that had a particular hydrologic history. A sediment core from a crater floor can be interpreted not just as a local lake deposit but as the downstream archive of an entire catchment, recording what happened upstream over long spans of time.

For me, that is the quiet revolution behind the new mapping. It turns Mars from a gallery of interesting features into a coherent, if long-dead, hydrologic system that can be studied with the same tools used on Earth. By tracing ancient mega watersheds, identifying 16 large river basins, and highlighting complex networks like the one near Idae, scientists have finally given us a planetary-scale blueprint of where water once ruled the Red Planet, a blueprint that will guide both robotic and human exploration for years to come, as emphasized in the work that mapped Scientists Map Mars large river drainage systems for the first time.

More from MorningOverview