Deep inside the Ring Nebula, astronomers have spotted a structure that should not exist: a narrow, glowing bar of iron stretching across the dying star’s remains. It is as if a red-hot metal rod has been driven through one of the sky’s most photographed smoke rings, and no one yet knows who, or what, did the forging. The discovery is forcing researchers to rethink how stars like the Sun die and what happens to the planets that once circled them.

The object is not a solid ingot but a bar-shaped cloud of ionized iron, blazing in wavelengths that only sensitive instruments can see. Its presence, and its sheer mass, challenge long-held assumptions about how heavy elements are distributed in planetary nebulae and whether shattered worlds might be hiding in the ashes of their parent stars.

Inside the Ring Nebula’s eerie new centerpiece

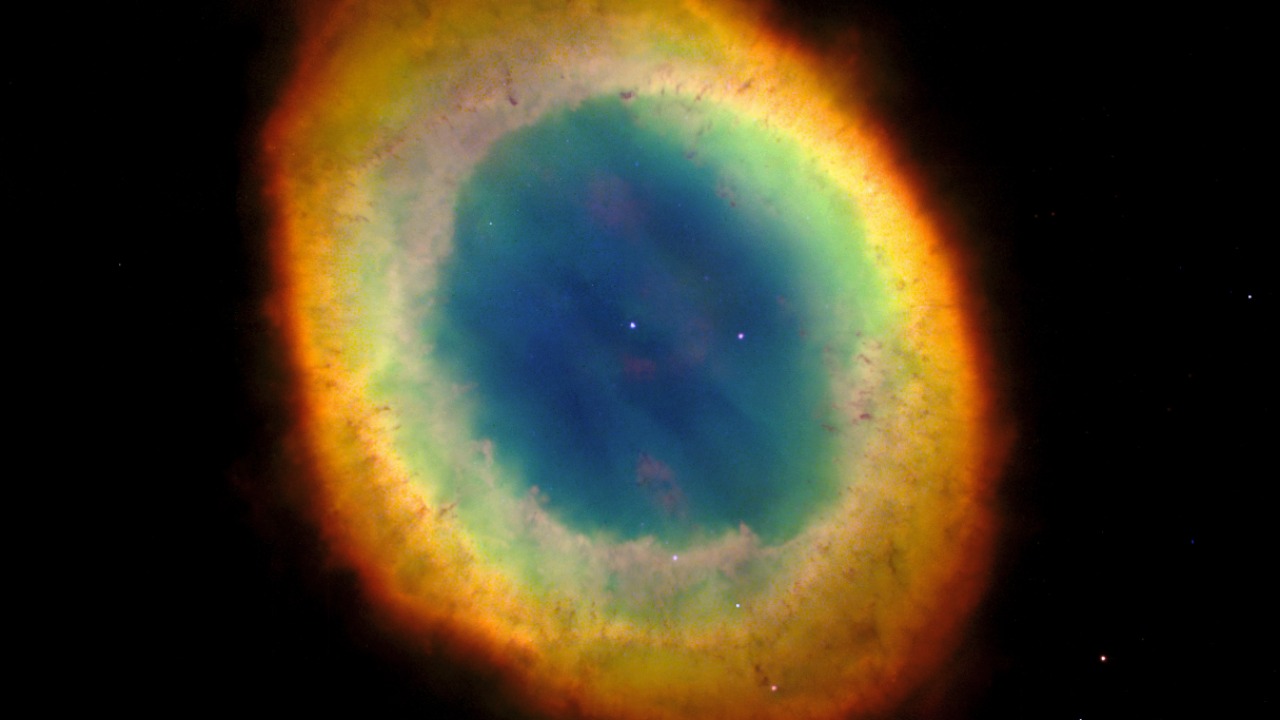

The Ring Nebula, cataloged as Messier 57, has long been a textbook example of what happens when a Sun-like star sheds its outer layers and leaves behind a hot core surrounded by a glowing shell of gas. First recorded in 1779 by the French astronomer Charles Messier, it sits in the constellation Lyra as a bright, nearly circular ring that amateur telescopes can easily pick out. That familiar doughnut of gas is mostly hydrogen and helium, but new observations reveal that deep within the nebula, a huge bar of iron is hiding in plain sight, cutting across the central region like a cosmic skewer, according to detailed mapping of iron deep inside the cloud.

The structure is not a neat, metallic rod. It is a bar-shaped cloud of ionized iron atoms, glowing in specific emission lines that stand out when astronomers isolate the right wavelengths. A European team led by researchers at University College London describes it as a mysterious bar-shaped cloud of iron inside the iconic Ring Nebula, with the iron mass comparable to that of Mars and concentrated along a narrow strip that runs through the nebula’s center, as highlighted in the initial announcement of the finding.

How astronomers pulled the iron bar out of the shadows

The iron bar did not reveal itself in pretty pictures alone. Astronomers combined high resolution imaging with spectroscopy, splitting the nebula’s light into its component colors to search for the fingerprints of different elements. When they processed the data, one feature leapt out: a narrow strip of ionized iron that appeared “as clear as anything” in the maps, a feature that had been completely missed in earlier, less sensitive surveys. The team’s analysis shows that this bar is not a minor quirk but a dominant structure in the inner nebula, a result that underpins the description of a colossal bar of iron hidden inside the Ring Nebula and comparable in mass to Mars.

To build that picture, the researchers used instruments capable of mapping velocities and chemical abundances across the nebula, turning the Ring into a three dimensional laboratory. The work, led by Dr Roger Wesson and collaborators, relies on detailed modeling of emission from iron and other elements to reconstruct how gas is moving and where heavy atoms are concentrated, a process laid out in the study by Roger Wesson et al. The result is a map in which the iron bar is not a faint curiosity but a dominant, linear feature that slices across the nebula’s heart.

A “Mars bar” of iron that should not be there

What makes the discovery so jarring is not only the shape but the amount of iron involved. The bar’s mass is estimated to be similar to that of Mars, meaning a single elongated structure inside the Ring Nebula contains as much iron as an entire terrestrial planet. In a planetary nebula that was expected to be dominated by lighter elements, such a concentration of heavy atoms is a surprise, especially when the surrounding gas is relatively diffuse. That is why some astronomers have taken to calling it a “Mars bar” of iron, a nickname that captures both its elongated form and its planetary scale, as described in reports that emphasize the massive iron content locked away in the structure.

Equally puzzling is the state of that iron. In many nebulae, iron is largely trapped inside dust grains, making it hard to detect in emission. Here, the iron appears as a distinct, ionized component, suggesting that dust has been destroyed or that the iron never condensed into grains in the first place. The bar is quite long and narrow, stretching across the inner nebula in a way that does not match the roughly spherical symmetry expected from a dying star’s outflow, a geometry that has left astronomers openly admitting that they do not yet know where it came from.

Clues from a dying star and its possible dead planets

The Ring Nebula is the remnant of a star that once resembled the Sun, now stripped down to a hot core that illuminates the surrounding gas. In standard models, such stars shed their outer layers in roughly spherical or mildly bipolar flows, with heavy elements mixed more or less smoothly throughout. The iron bar cuts against that expectation, hinting at a more violent or asymmetric history. One possibility is that the bar traces material from a disrupted planet or planetary core that was engulfed as the star expanded, concentrating iron along a preferred direction as the system evolved, an idea that fits with the notion of a colossal iron structure running through a nebula otherwise made mostly of hydrogen and helium.

Researchers are cautious about jumping to conclusions, but some see the bar as a potential signpost of planetary destruction. If a rocky world or a metal rich core spiraled into the dying star, its iron could have been stripped out and ejected along a particular axis, leaving behind a bar-like imprint. The narrow strip of ionized iron that stands out so clearly in the data is central to this line of thinking, and some scientists have suggested that confirming a “dead planet” origin for the bar could offer a preview of the fate of Earth when the Sun reaches its own red giant phase, a possibility that has been raised in discussions of how such a feature might reveal the fate of our own world.

Why this iron bar matters far beyond Lyra

For astronomers, the Ring Nebula has always been more than a pretty picture. It is a nearby laboratory for testing theories of stellar evolution, chemical enrichment, and the ultimate destiny of planetary systems. The discovery of a bar-shaped cloud of iron inside this iconic nebula, located in Lyra, adds a new layer of complexity to that role. It suggests that the late stages of Sun-like stars can produce highly structured, element rich features that standard models do not predict, a conclusion underscored by the description of a mysterious bar of iron at the nebula’s core.

The stakes are not purely academic. Our own Solar System will eventually pass through a similar phase, and the Ring Nebula’s iron bar hints that the endgame for planets may be more chaotic and more chemically diverse than once thought. If a Mars mass of iron can be concentrated into a single structure inside one nebula, it raises questions about how often stars recycle planetary material back into space in such focused ways. As lead observers continue to analyze data from instruments such as the WHT Enhanced Area Velocity Explorer, they are looking for additional clues in the velocities and temperatures of the gas, work that has been highlighted in coverage of how astronomers need to know about the bar’s origin and evolution.

More from Morning Overview