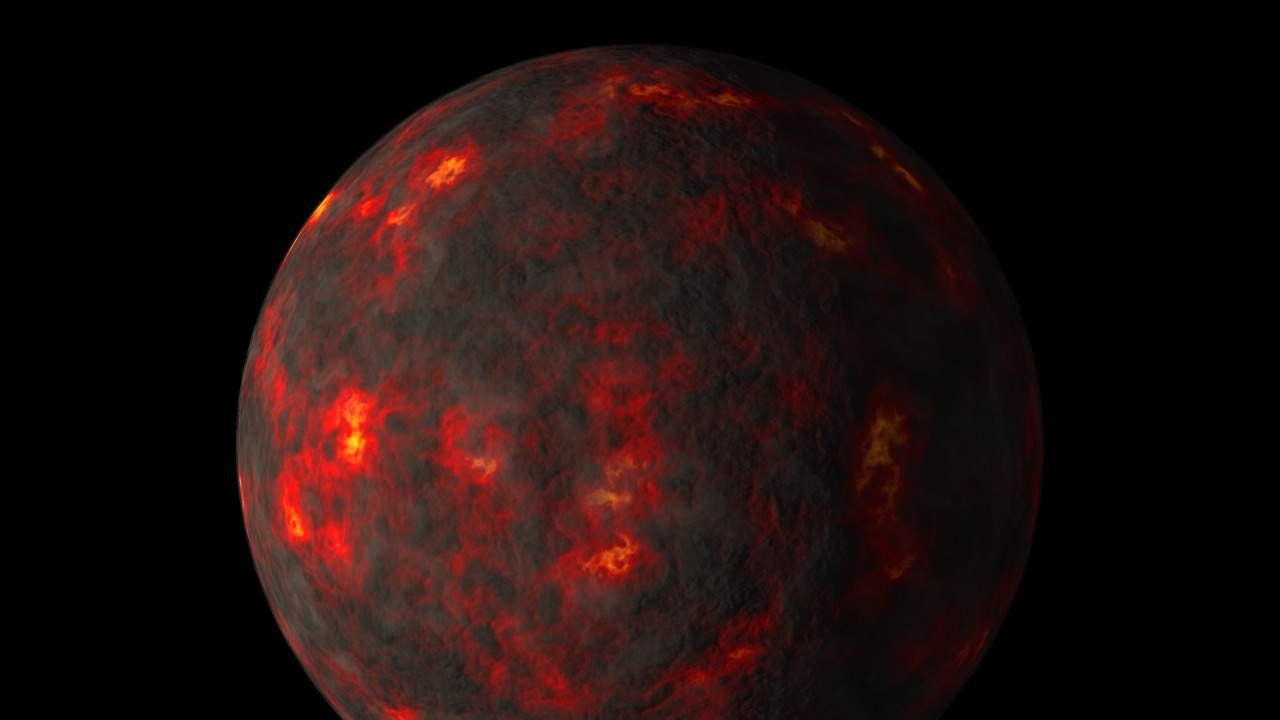

For years, astronomers have celebrated every hint of an ocean on a distant world as a potential foothold for life. Now a new wave of modeling argues that most of those supposed seas are illusions, and that many of the planets once billed as blue marbles are more likely wrapped in molten rock. The shift forces a rethink of how I interpret the faint signatures of exoplanet atmospheres and where I expect habitable environments to hide.

Instead of a galaxy filled with gentle “water worlds,” the emerging picture is a cosmos where magma, steam and buried oceans dominate. That does not kill the search for life, but it does move the most promising real estate away from the obvious candidates and toward more complex, layered worlds.

How “water worlds” turned into lava planets

The latest challenge to the ocean-filled vision comes from work highlighted in Jan reports that argue up to 98% of planets once tagged as “water worlds” are probably dominated by lava. In this view, the same spectral fingerprints that I might once have read as thick water vapor instead trace superheated atmospheres above incandescent surfaces. The key insight is that many of these planets orbit so close to their stars that any surface water would be rapidly stripped, leaving behind magma oceans that still produce strong signals in the infrared.

Those Jan findings build on the idea that what I see in a planet’s light is not a direct photograph but a puzzle of temperature, pressure and chemistry. The work suggests that when I interpret a steamy spectrum as evidence of global oceans, I may be folding in Earth-based bias about what water-rich atmospheres look like. In reality, the planets flagged as Water Worlds could be the most extreme lava planets yet, with molten mantles feeding volcanic plumes into skies that only mimic the signatures of cooler, wetter environments.

Sub-Neptunes, sinking water and the K2-18b wake-up call

The reclassification of “water worlds” did not come out of nowhere. Earlier work from ETH Zurich was prompted in part by the debate around K2-18b, a sub-Neptune about 124 light-years away that briefly looked like a poster child for a habitable ocean planet. When I look more closely at planets in this size range, the ETH team argues, the physics of high-pressure interiors means water does not stay as a surface ocean. Instead, it tends to migrate downward, forming deep layers of high-pressure ice or mixing into the mantle, while the outer envelope becomes dominated by hydrogen and helium.

In that framework, the class of objects once casually described as “Many sub-Neptunes” covered in global seas starts to look very different. The ETH Zurich models show that Neptunes in this mass and radius range are more likely to have stratified interiors where water is locked away at depth rather than forming Earth-like oceans. That conclusion dovetails with the lava-planet argument: if water is either buried or boiled off, then the inviting mental image of a shallow, sunlit sea on a sub-Neptune was always too optimistic.

Why oceans vanish: interior physics and steam worlds

To understand why the dream of ubiquitous ocean planets is fading, I have to follow the water. One line of research focuses on how liquid gradually disappears into a planet’s interior, where high pressures and temperatures transform it into exotic phases. Modeling work on Water disappearing into the mantle suggests that even if a young planet starts with a deep global ocean, geological processes can drag that water downward until the surface is left comparatively dry. Even though the accuracy of such calculations has some limitations, the researchers are confident enough to predict that many planets which once looked like ocean worlds will present bare or lava-dominated faces to telescopes such as the James Webb Space Telescope.

Another piece of the puzzle comes from the idea of “steam worlds,” planets that are rich in water overall but orbit so close to their stars that any surface ocean is converted into a thick, superheated atmosphere. In these cases, the boundary between ocean and sky effectively vanishes, leaving a deep envelope of vapor above a high-pressure interior. Work on such Scientists studying Neptunes with intermediate masses between that of Earth and Neptune shows that these steam worlds can have structures very different from anything in our solar system. From a distance, their spectra can resemble those of cooler, ocean-bearing planets, which is exactly the confusion that led to the overcount of “water worlds” in the first place.

Hycean hopes, shrinking but not gone

The reassessment has hit one particularly hyped category hard: so-called Hycean planets, worlds with hydrogen-rich atmospheres and deep oceans that were once touted as prime real estate for life. In the new study, In the modeling by Dorn and her team, sub-Neptunes evolve during their early lifetimes in ways that strip or bury much of their water, leaving far fewer true Hycean candidates than the percent envisioned for Hycean planets in earlier work. When I factor in the new lava-planet analysis that suggests 98% of supposed water-rich worlds are actually magma dominated, the Hycean category starts to look less like a broad class and more like a narrow niche.

Yet the same research that shrinks the Hycean population also refines where I should look next. The researchers found that the most water-rich atmospheres did not appear on planets formed far from their stars, where ice is abundant, but instead on worlds that migrated inward from intermediate distances. According to follow-up analysis, Sep results show that formation history matters as much as present-day location. That nuance means I can still search for planets with substantial water, but I have to combine atmospheric spectra with models of orbital migration and interior structure rather than relying on a simple “right size, right distance” checklist.

From distant exoplanets to Europa’s hidden ocean

If most distant “water worlds” are either lava planets or steam-shrouded sub-Neptunes, the most promising oceans for life may be closer to home. Work on Europa, Jupiter’s icy moon, points to a different pathway for habitable conditions, one that does not depend on a planet sitting in a narrow temperate band. A recent analysis on Europa’s interior argues that its subsurface sea could maintain chemical gradients and energy sources suitable for biology, even without sunlight. The Study Suggests a Pathway For Life where Conditions In Europa and its Ocean are controlled by interactions between the rocky mantle and the overlying water, with the composition of the nucleus varied between runs to test different scenarios.

For me, the contrast is striking. On one side are hot, close-in exoplanets where water either boils into a thick envelope or sinks into the core, leaving surfaces that are more like glowing lava lakes than Pacific basins. On the other are icy moons like Europa, where oceans are locked beneath ice but may be chemically rich and stable for billions of years. As the exoplanet field absorbs the realization that most “Water Worlds Might Actually Be Lava Planets, New Evidence Says We have Been Misreading the Signs of Life,” the search strategy is already shifting. Instead of chasing mirages of surface oceans on sub-Neptunes, I expect more attention to turn to layered worlds, from Europa to distant steam planets, where habitability depends on hidden interfaces rather than postcard-perfect seas.

More from Morning Overview