Tourists on the Wild Coast of South Africa have been stopping in their tracks at the sight of hundreds of huge silver fish turning in tight circles in water barely deep enough to cover them. For years, the slow, hypnotic rotation of these predators in the Mtentu Estuary has looked like a mystery, or even a distress signal. Now, a growing body of research on coastal fish behaviour suggests there may be a clear ecological logic behind the spectacle of 1,000 giant fish spinning in a South African estuary.

Rather than a mass stranding in the making, scientists now suspect the circling is part holding pattern, part feeding strategy, and part response to changing coastal conditions. The behaviour slots into a wider story about how powerful predators, seasonal baitfish and vulnerable estuaries are being reshaped by warming seas and human interference.

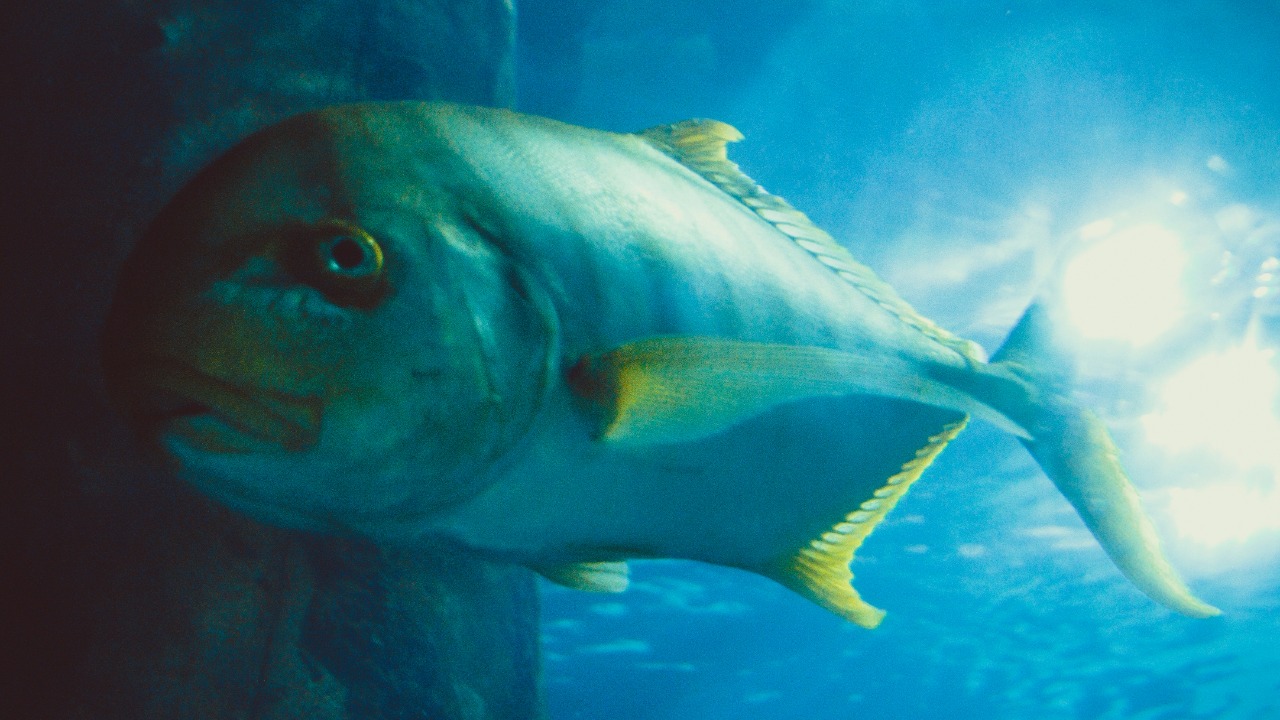

The strange circle of giant trevally

On calm days in the Mtentu Estuary, the water can suddenly seem to boil as large, torpedo-shaped fish gather and begin to wheel in a slow, deliberate carousel. Researchers estimate that around 1,000 giant trevally, also known as giant kingfish, can pack into this relatively small body of water at once. Each fish is a heavyweight in its own right, capable of topping 50 kilograms, yet here they move with almost choreographed precision, tracing the same looping path over and over.

The scene has become a minor social media phenomenon, with local operators sharing clips that show the fish gliding past kayaks and sandbanks in water so clear that every fin beat is visible. In one widely shared video titled “How lucky are we to experience this!? Watch till the end. The Giant Trevally (GTs or Giant Kingfish) in the Mtentu Estuary, South Africa,” the camera lingers on the dense school as it turns in unison, a living whirlpool of muscle and chrome. For casual viewers, the obvious question is whether these predators are trapped, confused or preparing for some dramatic event.

From viral curiosity to scientific hypothesis

Marine biologists who specialise in coastal systems have started to treat the Mtentu spectacle as more than just a curiosity. I see their emerging explanation as a blend of basic fish ecology and the specific quirks of South African estuaries. Giant trevally are powerful, wide-ranging predators, but they are also opportunists that will exploit any sheltered, food-rich pocket of water they can find. An estuary like Mtentu offers calm conditions, a steady supply of smaller fish and invertebrates, and a refuge from the pounding surf just beyond the mouth.

Researchers now suspect that the circling behaviour is a way for these predators to hold position in a confined space while they wait for the right feeding or migration cue. Instead of dispersing along the coast, they appear to stack up in the estuary, conserving energy by cruising in a slow loop rather than constantly sprinting against currents. The tight formation may also help them corral baitfish into the centre of the circle, turning the estuary into a kind of mobile trap. That interpretation fits with what anglers and scientists know about giant trevally elsewhere, where they are famous for coordinated hunting and sudden, explosive strikes.

Estuaries, “fresh water plugs” and the timing of escape

To understand why the fish linger and circle instead of simply heading out to sea, it helps to look at how South African estuaries behave. Many of these systems are intermittently closed, their mouths blocked by sandbars until heavy rain or surf cuts a channel to the ocean. When that happens, the sudden outflow of river water can create what local scientists describe as a THE FRESH WATER PLUG at the mouth. Observations from breached estuaries show that larger fish do not bolt for the open sea the moment the sandbar gives way. Instead, as one researcher put it, “What I have observed is that the fish don’t just rush out immediately. They slowly move downwards and start to filter out into the open ocean.”

Seen in that light, the circling trevally may be biding their time, waiting for the plug of fresh water to thin and for salinity and currents to stabilise before committing to a risky dash into the surf zone. Holding in a tight school gives them flexibility: they can respond quickly when conditions shift, but they are not wasting energy fighting an unfavourable flow. The Mtentu Estuary’s geometry, with its narrow mouth and relatively deep inner basin, likely accentuates this effect, encouraging the fish to stack up and rotate in place rather than spread out along the channel.

Lessons from the sardine run and ecological traps

The behaviour of the Mtentu trevally also echoes a much larger and better known South African phenomenon, the annual sardine run. Each winter, billions of small fish surge up the east coast in one of the world’s most spectacular wildlife events, drawing in sharks, dolphins, seabirds and even large baleen whales. Recent genetic work has shown that the sardines involved belong to a distinct eastern stock, and that their migration into warmer waters may be an ecological trap. The fish are following cues that once led to safe, cool nursery grounds, but now deliver them into warmer, predator-filled waters where survival is lower.

Analyses of the sardine run have highlighted how climate change and shifting oceanography can turn long-evolved behaviours into liabilities. As one study notes, the journey is so strenuous that the sardines that do survive the gauntlet of predators still struggle to reach a suitable nursery area with cooler waters. A companion analysis of South Africa’s massive sardine run frames the entire event as a case study in how spectacular wildlife gatherings can mask underlying stress. The trevally carousel in Mtentu is smaller in scale, but it may be shaped by the same forces: warming currents, altered prey distributions and the narrowing of safe habitats along a heavily used coastline.

Temperature, predators and a changing South African coast

Water conditions along the Wild Coast are shifting in ways that matter to both baitfish and their hunters. Giant trevally are sensitive to Water Temperature, and sudden changes can alter their feeding patterns and the availability of the smaller fish they rely on. When nearshore waters warm or cool rapidly, baitfish may retreat into estuaries where conditions are more stable, and predators follow. In that scenario, the Mtentu Estuary becomes a thermal and nutritional refuge, concentrating both prey and hunters into a tight space and encouraging the kind of dense schooling now seen from the air and shore.

At the same time, the broader South African coastline is being reshaped by human activity and climate-driven shifts. Analyses of South Africa in the context of Africa’s changing oceans point to altered current patterns, more frequent marine heatwaves and growing pressure on estuaries from development and pollution. In that context, the sight of 1,000 giant fish spinning in a South African estuary is not just a viral oddity. It is a visible signal of how predators are adjusting, in real time, to a coastline where the old cues that guided migrations and feeding are being scrambled, and where sheltered pockets like Mtentu are becoming critical waypoints in an increasingly unpredictable sea.

More from Morning Overview