NASA is facing a convergence of controversies, from delayed Moon missions to culture-war fights over telescope names and climate language, yet the agency often responds with clipped statements or technical briefings that leave the political stakes unspoken. The result is a perception that there is an “explosive scandal” it will not fully address, even when the underlying issues are hiding in plain sight. I see a pattern less of conspiracy than of institutional reflex, one that prizes engineering detail and bureaucratic caution over the kind of candid, values-based conversation the public increasingly expects.

Moonshots, heat shields and the silence around risk

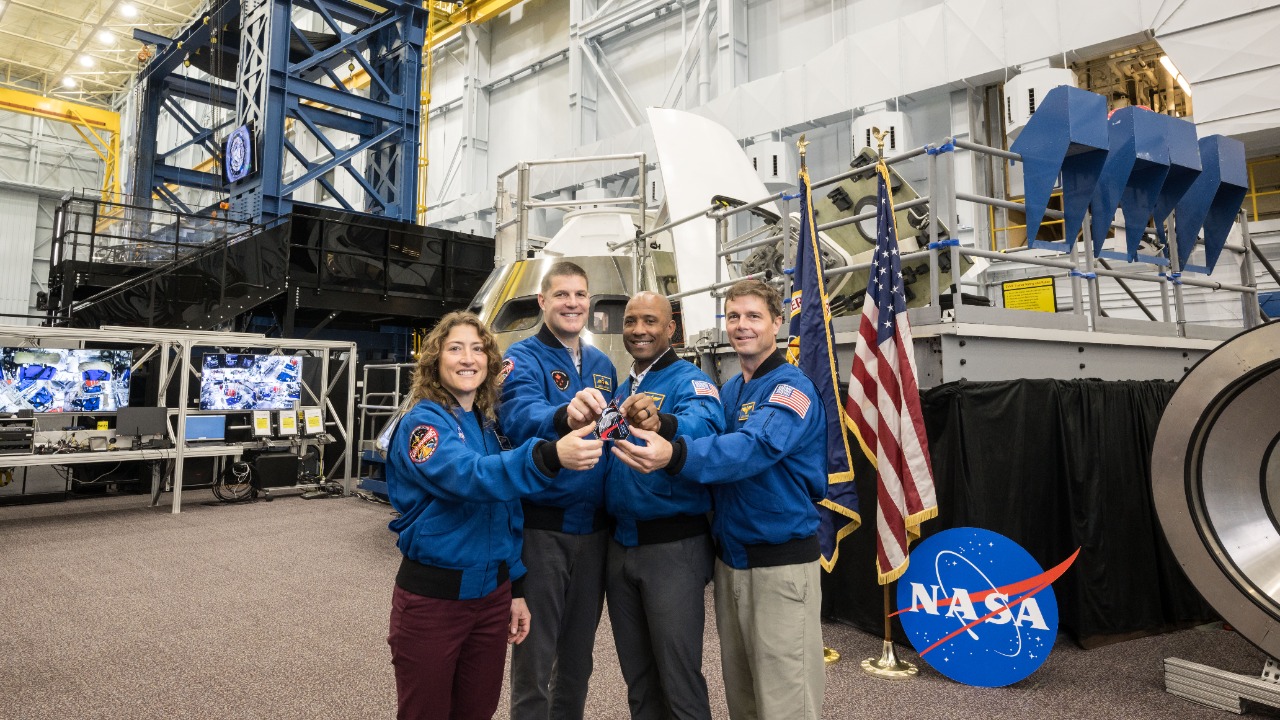

The most visible pressure point is the Artemis program, which is supposed to return astronauts to the Moon but has instead become a case study in how NASA talks around bad news. After the uncrewed Artemis I flight, engineers found unexpected damage to the Orion capsule’s heat shield, and critics faulted the agency for what they saw as an opaque response that downplayed the scale of the problem. When NASA later delayed the first crewed Artemis II mission, officials framed it as a technical necessity, but the communication gap between engineering reality and public reassurance only widened.

That delay followed a lengthy investigation into the heat shield and other systems, with NASA acknowledging that the Artemis Moon rocket would not carry people as soon as originally promised, even as it celebrated that, after a night of uncertainty, the vehicle ultimately took to the skies. The agency has since stressed that in space, delays are agonizing but safety comes first, yet it has been slower to spell out what the setbacks mean for the broader timeline. Internal leaders like Amit Kshatriya, the deputy associate administrator for NASA’s Moon to Mars program, have listed a host of new systems and technologies that must work together before astronauts can safely circle the Moon, but the public mostly hears about “schedule adjustments” rather than the deeper design questions those lists imply.

A landing date that keeps slipping into the future

The knock-on effect is that the promised Moon landing keeps receding, while NASA offers only partial explanations in public. Officials now concede that a crewed landing will not happen until at least 2027, a year later than the already ambitious plan, and that this revised date could shift again depending on how the Artemis programme proceeds. That admission came alongside a sober assessment that engineers still need to resolve issues with the Orion spacecraft and its heat shield, even as they juggle the politics of budgets and international partnerships that shape every step toward the lunar surface.

Complicating matters further, NASA has cancelled key pieces of its lunar infrastructure, including The VIPER rover that was supposed to launch in 2025 to scout for ice near the Moon’s south pole. When NASA said it was cancelling the mission, experts immediately questioned how a 2026 crewed landing could stay on track without the data that The VIPER was meant to collect. The agency has not offered a detailed public accounting of how it will replace that lost reconnaissance, and the combination of schedule slips and cancelled hardware feeds the sense that something bigger is wrong with the plan, even if the “scandal” is more about overpromising than outright misconduct.

James Webb, old records and a culture war NASA will not name

If Artemis exposes NASA’s discomfort with talking about technical risk, the fight over the James Webb Space Telescope reveals how reluctant it is to confront moral risk. For years, astronomers and activists have urged NASA to drop the name James Webb Space Telescope, citing archival evidence that James Webb, a former administrator, was involved in government meetings that targeted LGBTQ employees. NASA responded by announcing that it would not rename the James Webb Space Telescope despite controversy, and that it had not found sufficient grounds to change course after reviewing the allegations.

That decision landed poorly with many in the scientific community, especially after historians pointed to records showing that Webb planned and participated in meetings during which he handed over homophobic material as part of broader purges of queer federal workers. One detailed analysis argued that the records clearly show Webb’s role in those sessions, and that keeping the telescope named in his honor sends a message about whose pain counts in the story of space exploration. NASA has acknowledged the hurt but has largely confined its public comments to narrow statements about process, leaving the impression that it would rather ride out the storm than openly debate what kind of figures deserve to be immortalized on its flagship observatories.

Budgets, cancelled missions and the cost of not explaining

Behind the scenes, the agency is also being squeezed by money in ways that could reshape its entire portfolio, yet the public messaging often reduces this to bland talk of “tradeoffs.” NASA stands at the brink of a proposed budget that would shut down 41 space missions, after the White House Office of Management and Budget announced a plan on May to cancel a long list of spacecraft that have been exploring the Solar System for decades. The raw numbers are stark, but what is missing from most official statements is a frank discussion of what it means to walk away from working observatories and planetary probes that still have fuel in the tank and data to send home.

When I talk to scientists who rely on those missions, they describe a sense of whiplash: one year they are told to plan for long term campaigns, the next they are warned that a spreadsheet in Washington could end their work overnight. NASA’s public posture tends to emphasize that it is following administration guidance and congressional appropriations, which is true, but that framing sidesteps the deeper question of how the agency chooses which missions to fight for. The cancellation of The VIPER rover, the threatened shutdown of 41 missions and the shifting Artemis schedule are all facets of the same story, yet NASA rarely connects those dots in its own words, leaving outsiders to infer a pattern of quiet retreat from some of its most ambitious science.

Climate, conspiracy theories and the vacuum NASA leaves

The communication gap is perhaps most glaring on Earth itself, where NASA’s data underpins our understanding of global warming but its language sometimes seems to tiptoe around the politics. In a recent report, NASA stated that 2025 was the second-hottest year on record, with global surface temperatures 2.14°F above the 1951–1980 average, and listed Key Points about rising heat and the intensification of extreme weather events. Critics noted that the summary avoided explicit discussion of climate change in places where they expected it, arguing that the agency’s caution risked muting the urgency of its own findings at a time when the science is unequivocal.

At the same time, NASA is battling a different kind of narrative vacuum in orbit, where misinformation thrives when the agency does not speak quickly and clearly. The International Space Station, Located some 400 kilometers (248.5 miles) above Earth, recently had to organize the first-ever medical evacuation of astronauts, a reminder that human spaceflight is inherently risky even in low Earth orbit. While NASA and its partners did provide basic facts, the delay in fuller explanations allowed speculation to spread online, just as social media has been flooded with claims that Earth will briefly lose gravity next year because of a supposed programme dubbed Project Anchor. Fact checkers have debunked the idea that Earth will suddenly shed its gravity for seven seconds, but the episode shows how, in the absence of authoritative and accessible communication, conspiracy theories can fill the void.

More from Morning Overview