The United States has quietly embraced a new model of airpower built on cheap, expendable drones, taking direct inspiration from the Iranian systems that have terrorized battlefields from Ukraine to the Middle East. By reverse engineering Iran’s Shahed family and fielding its own low-cost attack drones at scale, Washington is signaling that mass, not exquisite hardware, will define the next phase of aerial warfare.

What began as an effort to understand and counter a threat has evolved into a race to copy and surpass it, with American engineers now producing Shahed-style drones that can be launched in swarms, guided by satellite links, and built fast enough to matter in a prolonged conflict. The result is a new class of weapons that blur the line between offense and defense, and that could reshape how both the United States and its rivals think about air superiority.

From Iranian experiment to global template

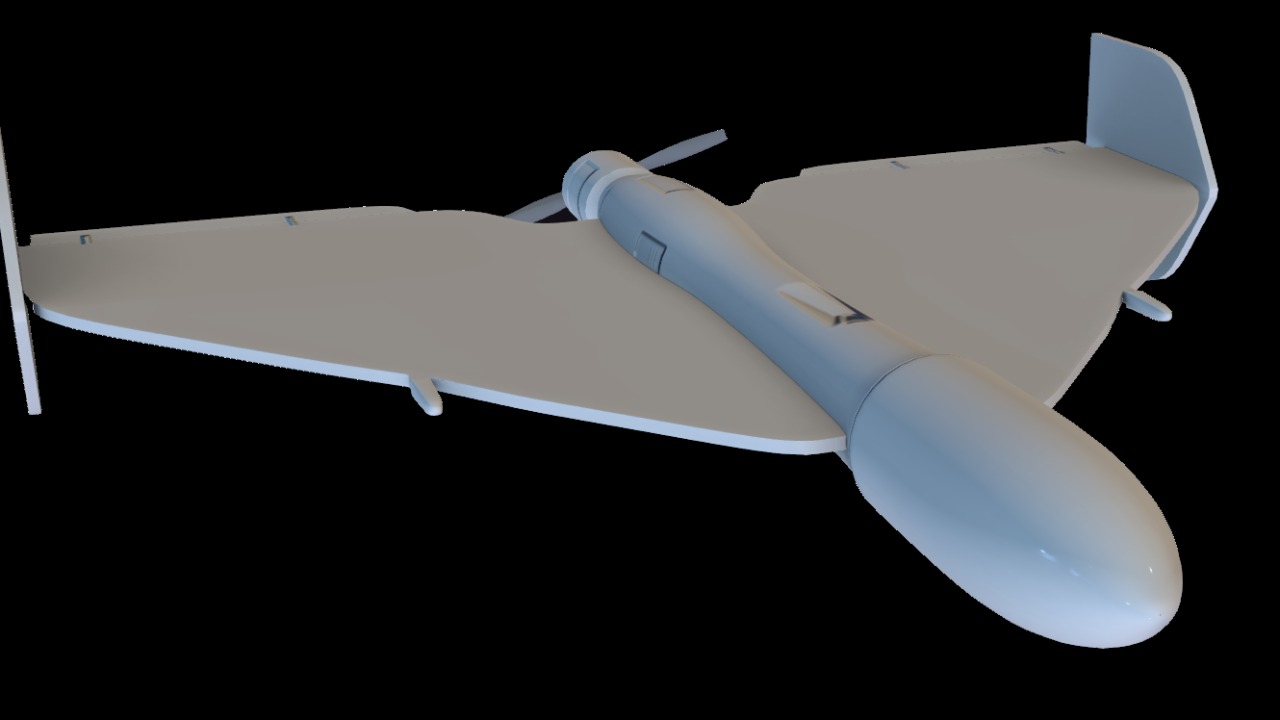

The starting point for this shift is the HESA Shahed 136, a one-way attack drone that Iran turned into a strategic tool by making it simple, rugged, and cheap enough to use in large numbers. The platform, produced by HESA and often described in Persian as a kind of “Witness” to distant targets, has been exported and adapted, including under the Russian designation Geran-2, and its very name, Shahed 136, has become shorthand for a new style of attritional air campaign that trades precision for volume and persistence, as detailed in technical profiles of The HESA Shahed 136.

Designed to fly low and slow with a distinctive engine note, the Shahed 136 has shown how a relatively crude airframe can still punch above its weight when used to saturate defenses and exhaust expensive interceptors. Reporting on its evolution notes that it was Designed in Iran and then modified and mass-produced under license by Russia, a partnership that turned the Shahed into a favorite weapon for long-range harassment and infrastructure strikes, a pattern that U.S. planners have studied closely through assessments of how it was Designed in Iran, modified and mass-produced under license by Russia, the Shahed.

Why Washington decided to copy the Shahed

For years, U.S. forces treated the Shahed threat primarily as a defensive problem, scrambling to find cheaper ways to shoot down volleys of drones without burning through high-end missiles. That mindset began to shift as commanders realized that the same attributes that made the Iranian system so troublesome for defenders, low cost, ease of production, and the ability to fly in large numbers, could be harnessed by The United States itself to saturate enemy airspace and complicate adversary planning, a logic that underpins the decision to field a low-cost drone explicitly built from the Iranian Shahed.

American engineers and planners concluded that trying to outspend adversaries with ever more exquisite platforms would not solve the problem of mass, especially in a potential conflict where thousands of targets might need to be struck or defended simultaneously. Instead, they opted to mirror the Shahed’s philosophy while layering on U.S. strengths in networking and guidance, a choice that has produced a family of drones that are cheap enough to be expendable but smart enough to be coordinated, a combination that reflects a broader shift in U.S. doctrine toward high-volume, low-cost systems that can be launched from ground, sea, and vehicle-mounted systems in ways described in early accounts of how The United States has quietly entered a new era of US reverse-engineers Iranian Shahed.

LUCAS: the American Shahed clone

The centerpiece of this effort is The LUCAS program, a Low Cost Unmanned Comb system that American officials describe as one of the most rapid reverse engineering projects in recent U.S. defense history. Built as a direct response to the Shahed 136, LUCAS takes the basic one-way attack concept and wraps it in a modular architecture that can accept different warheads, sensors, and communications packages, allowing commanders to tailor each wave of drones to specific missions while still benefiting from mass production, a design philosophy highlighted in technical briefings on how The LUCAS program represents one of the most rapid reverse-engineering efforts in recent U.S. defense history.

What sets LUCAS apart is not just its resemblance to the Shahed 136 in silhouette and mission profile, but the way American engineers have integrated it into a broader kill chain that includes satellite links, swarming algorithms, and real-time retasking. Reports on American Shahed-style systems describe how these Low Cost Unmanned Comb platforms can be launched in coordinated groups, share targeting data, and adjust their routes mid-flight, turning what was once a crude one-way munition into a semi-networked strike package, a capability that aligns with descriptions of American Shahed 136 Clones Sent To Middle East Have Satellite Datalinks and Swarming Capabilities, Low Cost Unmanned Comb.

Lucas in the field: swarms, datalinks and Middle East deployments

The first real test of this new approach has come in the Middle East, where American Shahed 136 Clones Sent To Middle East Have Satellite Datalinks and Swarming Capabilities have been deployed to support regional operations and to stress-test how well massed drones can integrate with existing air and missile defenses. These deployments show that the United States is not treating LUCAS as a lab curiosity but as an operational tool, using it to probe adversary radar coverage, soak up interceptor fire, and create openings for more valuable aircraft, a pattern that matches detailed accounts of how American Shahed 136 Clones Sent To Middle East Have Satellite Datalinks, Swarming Capabilities and are part of a broader Low Cost Unmanned Comb approach to regional security, as described in reporting on American Shahed.

Operational commanders in the region have emphasized that these drones are not meant to replace crewed aircraft or high-end missiles, but to complement them by providing a cheap, persistent presence that can be surged quickly in a crisis. Specifications from manufacturers in Arizona describe drones with an 8 ft wingspan that are robust enough for repeated handling yet inexpensive enough to be treated as expendable, a balance that has impressed naval leaders like Admiral Brad Cooper, who has highlighted how such systems can help manage threats that range from Iranian-style attacks on shipping to the kind of drone salvos that punched through Indian defences in May, details that align with accounts noting that According to specifications from SpektreWorks, a manufacturer based in Arizona, the drones have an 8ft wingspan and have already been used in scenarios that tested Indian defences.

Lucas versus Shahed: what actually changed

On the surface, the American clones look like straightforward copies of the Shahed 136, right down to the delta-wing layout and pusher propeller that have become visual shorthand for this class of drone. Under the skin, however, the differences are significant, with U.S. versions incorporating satellite datalinks, encrypted communications, and swarming logic that allow them to coordinate in ways the original Iranian systems could not, a contrast that is evident in technical breakdowns of how American Shahed 136 Clones Sent To Middle East Have Satellite Datalinks and Swarming Capabilities that go beyond the baseline Shahed design, as highlighted in reports on Clones Sent To Middle East Have Satellite Datalinks, Swarming Capabilities.

There are also differences in how the two systems are integrated into their respective militaries. Iran has used the Shahed 136 as a tool of strategic harassment, often launching small numbers at civilian infrastructure or symbolic targets, while U.S. doctrine envisions LUCAS as part of a layered strike complex that can be scaled up or down depending on the mission. The American approach leans heavily on networked targeting and real-time intelligence, using the drones as both sensors and shooters, a concept that builds on the original Shahed template but reflects a distinct philosophy about how to wage high-volume warfare, one that U.S. planners began to formalize when the Air Force sought an exact replica of the Shahed to help develop defenses and understand how it might be used in different theaters, as described in analyses of how the USAF seeks an exact replica of the Shahed to help develop defenses.

Inside the reverse engineering sprint

Behind the rapid fielding of LUCAS lies a crash program that pulled together captured wreckage, intelligence assessments, and commercial off-the-shelf components to replicate and then improve on the Shahed 136. American engineers treated the Iranian system as a baseline, mapping its airframe, propulsion, and guidance, then substituting domestic parts where possible and upgrading the electronics to support satellite control and swarming, a process that has been described as one of the fastest reverse engineering efforts in modern U.S. defense, with The LUCAS program singled out as a case study in how quickly American industry can respond when given a clear target, as detailed in reports that note how American engineers drove the LUCAS development.

That sprint was not just about copying hardware, it was also about building a production system that could scale. The United States leaned on a mix of traditional defense contractors and smaller firms to stand up assembly lines capable of turning out large numbers of drones without the long lead times that plague more complex aircraft. The result is a supply chain that can surge output in response to crises, a capability that has already been tested through deployments to the Middle East and through exercises that integrate LUCAS with ground-based launchers, naval platforms, and vehicle-mounted systems, a pattern that matches descriptions of how the United States has quietly entered a new era of low-cost drone production built from the Iranian Shahed and adapted for ground, sea, and vehicle-mounted systems, as outlined in technical overviews of US reverse-engineers Iranian Shahed.

Lucas on the launcher: how the US plans to use swarms

Operational footage and briefings show that U.S. forces are not treating LUCAS as a boutique capability, but as a workhorse that can be launched from simple rails, truck beds, and ship decks in large numbers. In one widely circulated clip, U.S. units deploy low-cost, one-way attack drones called Lucas to saturate enemy airspace and overwhelm air defenses, a vignette that captures the core concept of operations: use massed drones to force adversaries to reveal their radars, expend their interceptors, and open windows for follow-on strikes, a tactic that aligns with descriptions of how US deploys low-cost, one-way attack drones called Lucas to saturate enemy airspace and overwhelm air defenses.

Shorter clips highlight the same theme from a different angle, focusing on how the US military finally cloned the Iranian Shawhead drone and how Americans were able to rapidly produce and deploy Luc units in meaningful numbers. These videos underscore the speed with which the program moved from concept to field use, and they show launch crews treating the drones almost like artillery rounds, loading and firing them in quick succession rather than handling them as delicate aircraft, a cultural shift that reflects the expendable nature of the system and that is captured in footage noting that the US military finally cloned the Iranian Shawhead drone and that Americans rapidly produced and deployed Luc.

Defending against the weapon you just copied

There is an irony in the fact that the same U.S. Air Force that sought an exact replica of the Shahed to help develop defenses is now fielding its own version of the weapon at scale. Earlier efforts to build test articles and fly them at ranges in Florida were aimed at understanding how to detect, track, and intercept such drones, and those lessons are now feeding back into both offensive and defensive doctrine, with the Air Force using its experience with the Shahed 136 to refine radar settings, interceptor tactics, and electronic warfare options, as described in assessments of how the USAF seeks an exact replica of the Shahed drone to help develop defenses at an Air Force Base in Florida, a process detailed in reports that note how the service sought an exact replica of the Shahed drone to help develop defenses.

By building and flying its own Shahed-style drones, the United States is effectively training against itself, using LUCAS and related systems as stand-ins for Iranian and Russian weapons in exercises that stress air defense units and command centers. This dual-use approach, where the same class of drone serves as both a tool of offense and a testbed for defense, reflects a recognition that massed, low-cost systems are now a permanent feature of the battlefield, and that any military that hopes to survive and prevail will need to be as comfortable shooting them down as it is launching them.

The new logic of cheap mass warfare

What emerges from all of this is a new logic of airpower that prizes quantity, adaptability, and integration over sheer technological sophistication. The Shahed 136 showed that a relatively simple drone, produced in large numbers and used creatively, could punch holes in even well-equipped defenses, and the U.S. response with LUCAS and other clones suggests that Washington has absorbed that lesson, choosing to compete on the same terrain of low-cost mass while leveraging its advantages in networking and command and control, a trajectory that is evident in the way American Shahed-style systems now combine Satellite Datalinks, Swarming Capabilities, and Low Cost Unmanned Comb design in a single package, as described in technical analyses of Low cost unmanned systems.

For adversaries, this shift means that the United States is no longer relying solely on a small number of exquisite platforms that can be targeted and attrited, but is instead building a layered force that can absorb losses and keep fighting. For allies, it offers a template for how to build their own low-cost drone fleets, potentially using U.S. designs or partnering on production. And for civilians in potential conflict zones, it raises hard questions about how massed, expendable drones will affect the risk to infrastructure and urban areas, questions that will only grow more urgent as more countries follow Iran’s lead in fielding systems like the Shahed 136 and as more follow Washington’s lead in copying and upgrading them.

More from MorningOverview