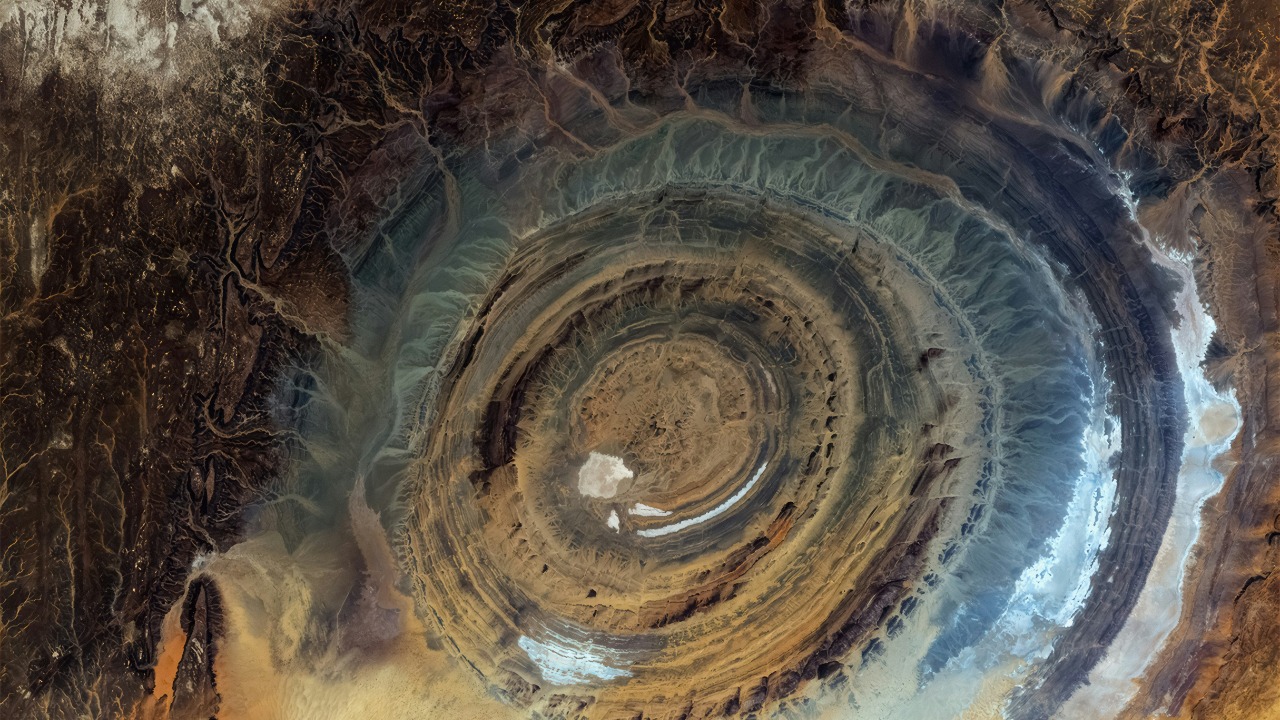

The Eye of the Sahara looks almost designed for satellite cameras, a perfect bullseye of rock and sand stamped into the western Sahara. From orbit, its nested rings stand out so sharply against the surrounding desert that they have become a kind of accidental logo for the age of Earth observation. I want to unpack how those orbital views have turned a remote geologic oddity into one of the most recognizable landforms on the planet, and what the science behind those hypnotic circles actually reveals.

A target in the desert that only satellites could fully reveal

On the ground in Mauritania, the Richat Structure is a broad, eroded dome of rock that rises and falls so gradually that its full shape is almost impossible to grasp. It took the vantage point of space for its concentric pattern to snap into focus, transforming a subtle uplift into a striking circular landmark that astronauts began using as a visual waypoint. From that height, the feature’s roughly circular outline and alternating light and dark bands read like a giant topographic fingerprint pressed into the Sahara, a pattern that early crews on orbital missions repeatedly photographed and described.

Modern sensors have sharpened that first impression into detailed portraits of the Eye’s geometry. High resolution imagery shows a ringed structure about 40 kilometers across, with darker ridges of resistant rock framing paler, sand-filled basins in between. In recent years, curated imagery from orbiting platforms has highlighted how the feature’s symmetry holds up across different viewing angles and seasons, with one Earth-observing snapshot capturing the full bullseye pattern in crisp blues and browns that trace the underlying geology.

How the Eye’s rings formed, layer by layer

Geologists now see the Eye not as an impact scar or a buried city, but as a deeply eroded dome where ancient rock layers have been peeled back in circular bands. The structure is interpreted as a broad uplift in the crust, where once-flat strata were pushed upward and then worn down by wind and water, exposing older rocks at the center and progressively younger layers toward the edges. The result is a natural cross section of the region’s geologic history, arranged in rings that happen to be large and regular enough to stand out from orbit.

Those rings are not uniform, and their differences help explain the Eye’s appearance in satellite images. Harder quartzite and other resistant rocks form the raised, darker arcs that catch low-angle sunlight, while softer sedimentary units erode into lower, sandier troughs that appear lighter from space. Detailed descriptions of the structure’s composition, including its mix of sedimentary and volcanic rocks and the way those units weather, have been laid out in accessible explainers on the Eye’s geology, such as a breakdown of the eroded rock dome that underpins the feature’s concentric pattern.

From impact myth to eroded dome: what the science says

For years, the Eye’s near-perfect circle and central uplift fueled speculation that it might be an impact crater, perhaps even linked to mass extinction events. The symmetry, the apparent central high, and the surrounding rings all looked, at first glance, like classic hallmarks of a large collision. That idea fit neatly with popular fascination around craters and cosmic catastrophes, and it lingered in public imagination long after fieldwork began to point in a different direction.

Closer study of the rocks, however, has undercut the impact hypothesis. Researchers have not found the shocked minerals, melted glass, or other diagnostic signatures that large meteorite strikes typically leave behind. Instead, they see a pattern of uplift and erosion more consistent with a structural dome, where internal tectonic forces raised the crust and subsequent weathering sculpted the rings. Detailed reporting on the Eye’s geology has emphasized this consensus, describing it as Mauritania’s giant rock dome rather than an impact scar, and highlighting how the absence of impact markers shifted scientific opinion.

Why the Eye pops so vividly in satellite imagery

Part of the Eye’s visual power comes from the way its geology interacts with light and atmosphere in satellite views. The Sahara’s generally uniform sand plains create a muted backdrop, so any deviation in color or texture stands out sharply. In the Eye, alternating bands of dark, resistant rock and lighter, sand-filled depressions create a natural contrast pattern that sensors pick up easily, especially when the sun is low and shadows accentuate the ridges. The circular arrangement of those bands amplifies the effect, turning what might otherwise be subtle stripes into a graphic, almost logo-like form.

Different satellite instruments accentuate different aspects of that pattern. Multispectral imagers can separate mineral signatures and moisture content, revealing variations in rock type and surface conditions that the human eye would miss. Long-running missions have used those tools to track how the Eye’s appearance shifts with changing light and atmospheric conditions, with one Landsat-based analysis showing how decades of consistent imaging have captured the structure’s rings in visible and infrared wavelengths. Those data sets turn a photogenic curiosity into a long-term record of erosion, dust movement, and subtle environmental change across the dome.

Europe’s view from orbit and the Eye’s role in Earth monitoring

European satellites have added their own perspective on the Eye, framing it not just as a curiosity but as a benchmark for Earth observation. High resolution imagery from platforms in polar orbit has captured the structure in different seasons and atmospheric conditions, revealing how dust storms, cloud shadows, and changing solar angles alter its appearance. Those images are often used to illustrate the capabilities of modern sensors, because the Eye’s clear geometry makes it easy to see how resolution, color channels, and viewing angles affect what analysts can extract from a scene.

Recent releases from European missions have highlighted the Eye as part of a broader portfolio of desert and arid-region monitoring, showing how the same instruments that produce dramatic visuals also track land degradation, water scarcity, and dust transport. One widely shared view of the Eye from a European platform, presented as an Earth from Space feature, underscores how the structure serves as both a showpiece and a calibration target. Its stable geology and strong contrast make it a useful reference point when engineers and scientists check sensor performance over time.

How NASA has turned the Eye into a teaching tool

NASA’s Earth-observing programs have repeatedly spotlighted the Eye as a way to explain remote sensing and basic geology to a broad audience. The structure’s clean rings and isolated setting make it an ideal example when illustrating how satellites capture large-scale patterns that are invisible from the ground. Educational features walk through the process of interpreting the imagery, from identifying the central uplift to tracing the concentric bands that mark different rock layers, and then linking those visual cues to the underlying geologic story.

Those efforts extend beyond a single mission or instrument. Imagery from multiple NASA platforms has been curated to show the Eye in different color composites and resolutions, helping readers understand how each sensor reveals different facets of the same feature. One widely circulated image set, presented as a space-based portrait of the Eye in Mauritania, pairs the striking visual with explanations of the dome’s formation and the role of erosion in carving its rings. That combination of aesthetics and clear explanation has turned the Eye into a staple of classroom discussions about Earth science and satellite technology.

From astronaut snapshots to viral posts: the Eye’s internet life

As satellite and astronaut images of the Eye have circulated online, the structure has taken on a second life as a viral visual. Its near-perfect circles and high contrast make it a favorite on image-driven platforms, where users often encounter it stripped of context and then go searching for the story behind the pattern. That cycle of fascination and explanation has helped pull a relatively obscure geologic dome into mainstream awareness, especially among people who might never have heard of Mauritania or the Richat Structure otherwise.

Community-driven spaces have amplified that effect by pairing high resolution imagery with informal commentary and questions. One widely shared post on a space-focused forum, for example, showcases the Eye as seen from orbit and invites viewers to zoom in on the intricate textures of its ridges and basins, with the user-curated image thread prompting discussions about its origin and scale. That kind of grassroots engagement often leads readers toward more detailed scientific resources, turning a moment of visual curiosity into an entry point for learning about geology and remote sensing.

Science communication and the Eye’s media presence

Science communicators have leaned into the Eye’s visual appeal to draw audiences into deeper conversations about Earth processes. Short explainers and picture-of-the-week features use the structure as a hook, then walk readers through concepts like uplift, erosion, and stratigraphy. By starting with a dramatic satellite view and then zooming into the details of rock types and weathering, those pieces bridge the gap between eye-catching imagery and the slower, more methodical work of geologic interpretation.

Some outlets have framed the Eye as a case study in how remote sensing reshapes our understanding of familiar landscapes, emphasizing that its full form only became clear once humans began looking back at Earth from orbit. A concise feature that presents the Eye as a weekly image highlight illustrates this approach, pairing the photograph with a straightforward explanation of the dome’s structure and the role of erosion in carving its rings. That format respects the audience’s time while still grounding the spectacle in solid science.

Speculation, storytelling, and the pull of mystery

The Eye’s symmetry and isolation have also made it a magnet for speculation, from fringe theories about lost civilizations to imaginative links with ancient myths. Those narratives often start with the undeniable strangeness of a perfect circle in the middle of a vast desert, then layer on conjecture that is not supported by field evidence. While such stories can be engaging, they tend to gloss over the detailed mapping, sampling, and analysis that geologists have carried out across the structure, work that consistently points to uplift and erosion rather than human or extraterrestrial engineering.

Responsible coverage has tried to balance that sense of wonder with clear boundaries between evidence and conjecture. Some long-form explainers explicitly address popular myths before walking readers through the data that contradicts them, using the Eye as a teaching moment about how science tests and discards appealing but unsupported ideas. A recent analysis that uses new orbital imagery to highlight the Eye’s details follows this pattern, acknowledging the structure’s role in speculative storytelling while grounding its conclusions in observed rock types, structural patterns, and the absence of impact signatures.

Video flyovers and the immersive view from above

Advances in visualization have turned static satellite images of the Eye into dynamic flyovers that simulate what it would be like to soar above the structure. By stitching together high resolution imagery and digital elevation models, producers can create smooth passes that dip into the central dome, skim along the ridges, and pull back to reveal the full bullseye pattern in context with the surrounding Sahara. Those sequences help viewers appreciate the Eye’s scale and relief, which can be hard to grasp from a single overhead frame.

Some of these visualizations are packaged as short documentaries that blend orbital views with on-the-ground footage and expert commentary. One widely viewed segment, available as a video exploration of the Eye, uses animated camera paths to trace the concentric rings while narrators explain the dome’s formation and the evidence against an impact origin. By combining motion, narration, and annotated imagery, these pieces make the Eye’s complex geology more accessible to audiences who might not seek out written explainers.

Why the Eye matters for understanding deserts and deep time

Beyond its visual appeal, the Eye offers a rare window into the deep history of the Sahara and the forces that shaped it. The exposed rock layers in its rings record shifts in environment and climate over hundreds of millions of years, from ancient seas to more recent arid phases. By reading those layers like pages in a book, geologists can reconstruct how this part of Africa evolved, how tectonic forces lifted and warped the crust, and how erosion gradually sculpted the present landscape. The Eye’s circular cross section makes those transitions unusually easy to trace, since each ring corresponds to a different slice of time.

Remote sensing has amplified that scientific value by making it possible to map the structure comprehensively and non-invasively. High resolution imagery, spectral data, and elevation models allow researchers to correlate surface patterns with field observations, refine their understanding of the dome’s internal structure, and monitor ongoing erosion. Public-facing explainers that walk through the Eye’s formation, such as a detailed overview of its uplifted and eroded strata, underscore how a single photogenic feature can anchor serious research into tectonics, climate history, and desert geomorphology. In that sense, the Eye is more than a satellite showpiece; it is a working laboratory etched into the Sahara, one that orbiting cameras help scientists and the public read together.

More from MorningOverview