For most of the past 70 years, fusion energy has been shorthand for a promise that never quite arrived, a running joke about a technology that was always a few decades away. That timeline has shifted. A wave of scientific breakthroughs, commercial projects and government road maps now points to fusion machines moving from physics experiments to real infrastructure within the working lives of today’s engineers.

The hype has not disappeared, but it is finally colliding with hardware, construction sites and detailed deployment plans. I see a field that still faces brutal engineering and economic tests, yet now has enough momentum that the burden of proof has flipped: skeptics must explain why this surge of capital, policy and science will suddenly stall.

From distant dream to tangible progress

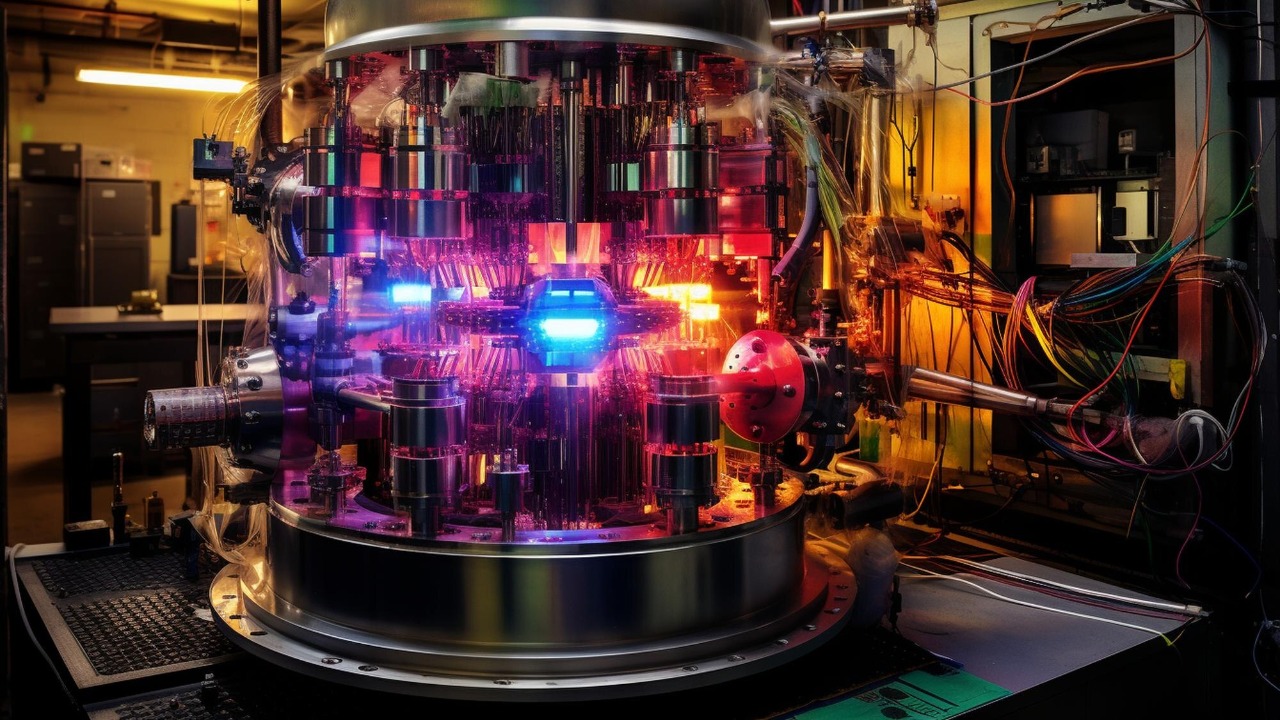

For years, fusion sat on the horizon as a kind of scientific mirage, impressive on paper but stubbornly out of reach in practice. That perception is changing as researchers report that in 2026, progress is “tangible,” with a growing number of devices hitting performance milestones and a pipeline of new machines under construction, while investment, both public and private, is accelerating across the sector. That shift is visible in the way fusion is now described as advancing through multiple technology pathways, with magnetic confinement, laser-driven approaches and alternative concepts all being pushed in parallel to reduce risk, cost and development time, rather than betting on a single grand machine.

Yet the field’s new confidence is tempered by a more sober understanding of its unique challenges. Analysts stress that one of fusion’s defining problems is not just achieving a burst of net energy, but sustaining and controlling a plasma in a way that can be engineered into a reliable power plant, a point that is now central to industry insight and technical road mapping. As I read it, the story has moved from “if” to “how fast,” with the question no longer whether fusion can work in principle, but how quickly the sector can turn laboratory gains into bankable assets.

Breakthrough science solves 70‑year problems

The most striking sign that fusion is entering a new phase is the way long standing physics roadblocks are falling. Scientists at the University of Texas report solving a 70-year-old nuclear fusion problem by finding a way to help tokamaks stop dangerous electrons from escaping and striking the walls of the reactor, a flaw that has haunted designers since the earliest machines. Other teams describe a powerful new technique that lets Scientists control magnetic systems ten times faster, tackling another major obstacle in keeping super heated plasmas stable.

Those advances are part of a broader pattern in which Scientists are finally closing a 70-year fusion flaw that once made clean, cheap energy feel remote, and now directly influences how we design these reactors. In parallel, the 2024 GESDA Science Breakthrough Radar highlights nuclear fusion as a technology on the cusp of practical impact, pointing to the giant Tokamak machine in southern France as a focal point for these scientific gains. When I connect these dots, the picture that emerges is of a field that has finally cracked some of its oldest puzzles and is now racing to embed those solutions in real hardware.

Megaprojects and private plants reshape the map

On the ground, the most visible symbol of fusion’s ambition remains ITER, the vast Tokamak complex rising on a 180 hectare site in southern France. The project’s own updates describe What is New on that site, with Featured construction milestones even as the schedule has slipped. Full operation of the ITER tokamak, which uses magnets to squeeze super heated plasma while burning deuterium and radioactive tritium as fuel, is now expected later than first planned, with ITER now planning to use a more complete machine from the start.

Those delays have forced a reset, with project leaders explaining What has caused the delays and why There are still strong commitments to support project success. Yet even as ITER wrestles with schedule risk, private developers are moving faster. In July, In July, Helion broke ground on what it calls the first ever commercial fusion power plant in Malaga, Chelan County, a facility that aims to generate electricity and be ready to supply the grid, signaling that private capital is no longer waiting for the big international experiment to finish.

Commonwealth Fusion and the ARC era

Among the private players, Commonwealth Fusion Systems has become a bellwether for how quickly fusion might scale. The company describes itself as building on Decades of worldwide, government sponsored research in fusion science to deliver commercial fusion energy to combat climate change. CFS is now constructing a fusion demonstration machine at its headquarters in Devens, Massachusetts, with expectations that this device will produce net energy and influence the power sector in a substantial way, according to CFS focused reporting.

Inside the company, activity is intense. Leaders say that in the last six months they have hit many milestones and that work in Devons at the Spark facility is at an all time high, a picture captured in an Devons update that highlights the Spark site. At CES 2026 in Las Vegas, CMO Joe Plesco of Commonwealth Fusion Systems described how the company is positioning its technology for real markets, a message delivered in a Las Vegas interview that underscored how far fusion has moved into mainstream tech conversations.

Road maps, markets and the new fusion economy

Governments are now racing to keep up with this private momentum. In the United States, DOE has released a fusion science and technology road map that leans on a strategy described as Through the Build, Innovate, Grow, with DOE and its partners across national laboratories, industry, universities and allied nations working to accelerate commercial deployment, as laid out in the Through the Build framework. China has emphasized its own fusion energy goals as part of its 15th Five Year Plan for economic development, while European policymakers are exploring how fusion might fit into future power generation for Europe, showing that this is now a geopolitical as well as a scientific race.

Markets are starting to price in that possibility. The Global Nuclear Fusion Energy Market Report, covering 2026 to 2046, notes that Near term Projections Suggest the First Commercial Fusion Power Plants Coul begin operation between 2030 and 2035, a forecast that anchors investor expectations in a specific window, according to the Global Nuclear Fusion. Analysts tracking Increased Private Investment say Total private investment is expected to ramp as tech giants and hyperscalers increase their stakes in fusion companies by the end of 2026, a trend highlighted in Increased Private Investment commentary.

More from Morning Overview