Far below our feet, two colossal structures the size of continents sit atop Earth’s core, one beneath Africa and one beneath the Pacific Ocean. These dense, hot anomalies have puzzled geophysicists for decades, and new research now suggests their origins may be stranger and more violent than anyone expected. I want to trace how scientists uncovered these hidden giants, why the African structure in particular is so unusual, and how an ancient planetary collision might have seeded the mysterious material that still shapes our world today.

What scientists actually found under Africa and the Pacific

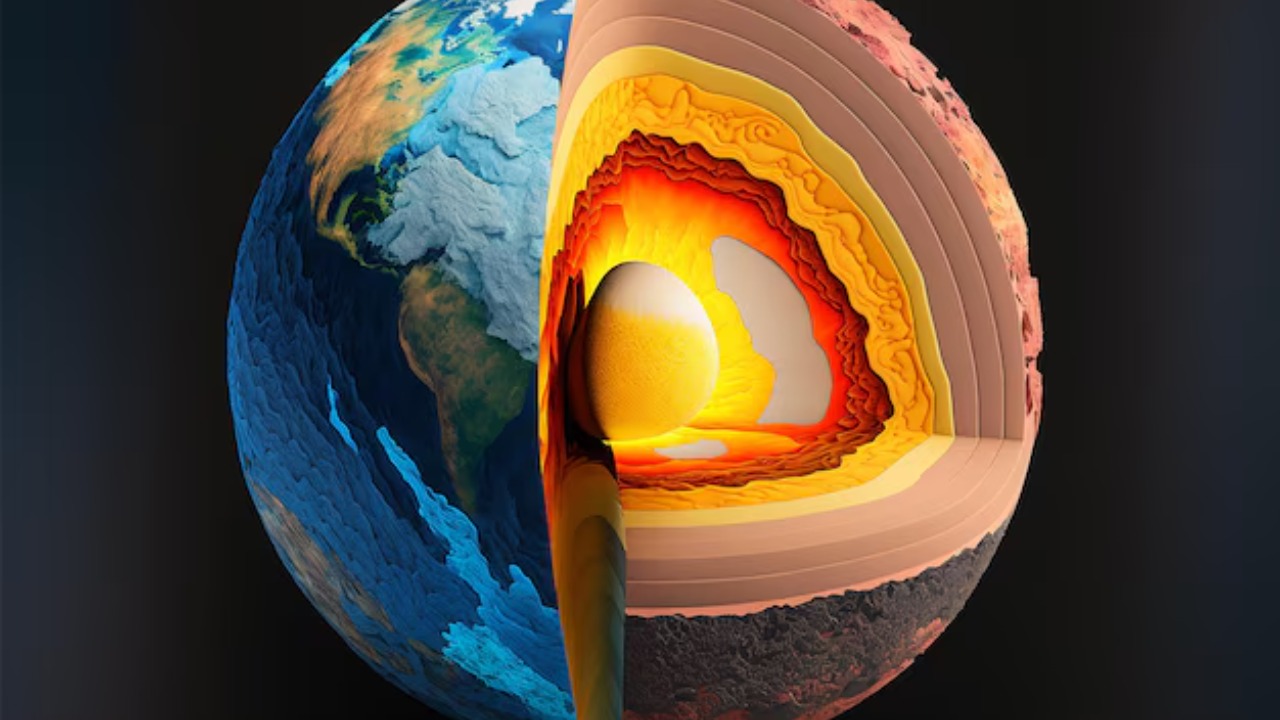

When geophysicists first mapped seismic waves passing through the deep mantle, they noticed two vast regions where those waves slowed down, signaling material that is hotter or compositionally different from its surroundings. These regions, known as “large low velocity provinces,” or LLVPs, sit near the boundary between the mantle and the outer core, one beneath Africa and the Atlantic and the other beneath the Pacific Ocean. The African structure stretches under Africa, Spain, and parts of the Atlantic, while its Pacific counterpart sprawls beneath the Pacific Ring of Fire, and both are so large that each rivals the size of our Moon.

Tomographic models of Earth’s lowermost mantle show these anomalies as nearly antipodal patches of reduced seismic velocities, with one LLVP centered beneath Africa and the other beneath the Pacific, confirming that they are broad, coherent features rather than scattered blobs of hot rock. In these images, the African and Pacific regions stand out as massive protrusions on the core, rising hundreds of kilometers into the mantle and dominating the lowermost layer of the planet. Researchers now routinely describe them as continent scale structures, with tomographic images and detailed seismic models converging on the same basic picture of two giant anomalies beneath Africa and the Pacific.

How seismic waves revealed the “giant blobs”

The only reason we know these deep structures exist is that earthquakes send seismic waves through the planet, and those waves behave differently when they cross unusual material. As compressional and shear waves travel through the mantle, they speed up in cold, rigid rock and slow down in hotter or compositionally distinct regions, leaving a subtle but measurable fingerprint in global seismograph records. By inverting thousands of these travel times, geophysicists in the 1980s and beyond reconstructed three dimensional maps of the deep mantle and saw the African and Pacific LLVPs emerge as coherent, slow velocity zones.

In these regions, seismic waves move with distinct sluggishness, implying that the material is not only hotter but also chemically different from the surrounding mantle. The anomalies are broad, low seismic wave speed patches in Earth’s lower mantle, and their boundaries appear sharp in some directions and diffuse in others, hinting at complex internal structure. Through these patches, the seismic waves travel with distinct sluggishness, a behavior that has been used to argue that the LLVPs are compositionally dense piles rather than simple thermal plumes, a view supported by detailed modeling of through going wave paths and by recent work that treats them as long lived, chemically distinct structures.

Why the African structure looks so different

Although the African and Pacific LLVPs are often discussed as a pair, they are not twins, and that asymmetry is one of the biggest clues to their origin. The African structure appears taller and less stable, rising higher above the core mantle boundary than the Pacific anomaly and showing more evidence of interaction with mantle plumes that feed surface volcanism. Seismic observations indicate that the African LLVP may be more dynamic, with a geometry that suggests it has been reshaped by upwelling hot rock and by the long term pattern of mantle convection beneath the African plate.

Studies that compare the two regions find that the African LLVP is likely less dense and less stable than the Pacific LLVP, which seems more compact and gravitationally anchored. This difference may help explain why Africa’s surface sits at a higher average elevation than many other continents and why the region hosts unusual volcanic activity and rifting. One analysis of the origin of the vast height difference between the African and other plates points directly to the African Large Low Shear Velocity Province, arguing that its buoyant, elevated structure beneath Africa and the Paci region has helped lift the continent over tens of millions of years, with Seismic data suggesting that the African LLVP is less stable than the Pacific LLVP and more prone to generating plumes.

Shape shifters at the core mantle boundary

As imaging has improved, scientists have realized that these deep structures are not static blocks but evolving, irregular masses that can change shape over geologic time. Some models depict the LLVPs as sprawling, continent like plateaus of dense material that can merge, split, and migrate as mantle convection stirs the deep interior. In this view, the African and Pacific anomalies behave almost like tectonic plates of the deep mantle, with their edges interacting with subducting slabs and their tops feeding hot upwellings that eventually reach the surface as volcanic hotspots.

High resolution seismic studies show that the boundaries of the LLVPs are sharp in some places and gradational in others, suggesting that they may be surrounded by smaller scale structures such as ultra low velocity zones and plume roots. Deep in the Earth beneath us lie these two giant blobs of anomalous material, and some researchers describe them as shape shifters that can reorganize over hundreds of millions of years, much like continents and supercontinents at the surface. Visualizations of Earth’s blobs as imaged in seismic tomography highlight the African blob at the top and the Pacific blob at the bottom, with Two Giant Blobs Lurk Deep Inside Earth, And It Looks Like They behaving as long lived but evolving features at the core mantle boundary.

From “weird blobs” to key players in Earth’s geology

For a long time, the LLVPs were treated as curiosities in seismic maps, but that view has shifted as researchers have linked them to some of Earth’s most dramatic surface phenomena. The African anomaly in particular has been implicated in the continent’s elevated topography, its rift systems, and its pattern of volcanism, including hotspots that do not sit neatly on plate boundaries. By acting as reservoirs of hot, possibly compositionally distinct material, the LLVPs may help organize where mantle plumes rise, which in turn influences where supervolcanoes, flood basalts, and long lived volcanic chains appear at the surface.

One line of work argues that the two giant blobs in Earth’s mantle may help explain Africa’s weird geology, including its high plateau and the clustering of volcanoes along the East African Rift. In this scenario, a massive blob of material under Africa could be feeding plumes that thin the lithosphere and drive uplift, while the Pacific LLVP under the Pacific Ring of Fire plays a similar role in organizing subduction related volcanism. Researchers studying 2 giant blobs in Earth’s mantle have suggested that the height of each blob, roughly 1,600 to 1,800 kilometers, and their interaction with subducted slabs help control where plumes form, a view supported by models that tie Africa’s unusual surface features to the deep Earth, Africa anomaly.

New evidence that the blobs are chemically distinct

As seismic data have accumulated, a consensus has emerged that the LLVPs are not just hotter mantle but also compositionally different, with higher densities that help them resist being mixed away. Detailed analyses of wave speeds and attenuation suggest that the material inside these provinces has unusually high iron content and perhaps other chemical signatures that set it apart from the surrounding mantle. This compositional contrast would explain why the LLVPs can persist for billions of years even as convection constantly churns the rest of the mantle.

Recent work on the unique composition and evolutionary histories of large low velocity provinces describes them as broad, low seismic wave speed anomalies in Earth’s lower mantle beneath Africa and the Pacific Ocean, with properties that require both thermal and chemical contributions. One study proposes that crustal material subducted over millions of years was stirred through the mantle and accumulated to form the LLVPs, concentrating dense, recycled rock at the base of the mantle. In this view, the two “large low velocity provinces” are long term repositories of subducted crust and other dense components, with Abstract level modeling and geochemical arguments supporting the idea that they are chemically distinct piles rather than simple thermal anomalies.

The Theia hypothesis: alien remnants inside Earth

The most provocative idea to emerge in recent years is that the LLVPs may be the buried remains of an ancient planetary body that collided with the proto Earth. In this scenario, a Mars sized object known as Theia slammed into early Earth in the same giant impact that created the Moon, and parts of Theia’s mantle sank to the base of Earth’s mantle, where they pooled into the dense blobs we now see as LLVPs. Because Theia’s material would have been compositionally distinct and possibly richer in iron, it could naturally form the kind of dense, slow velocity provinces that seismic studies detect beneath Africa and the Pacific.

Researchers who favor this view interpret the LLVPs as regions with unusually high iron content whose increased density and temperature slow down seismic waves, consistent with the observed low velocities. They argue that parts of the Theia materials sank to and accumulated at the base of the mantle, eventually forming the large low velocity provinces, and that these remnants still influence mantle dynamics and surface volcanism today. An artistic illustration of Theia impacting the proto Earth captures this idea visually, but the core claim is geophysical, with They interpreted as dense, iron rich remnants of an ancient planetary collision that still sit beneath Africa and the Pacific.

Reconstructing billions of years of deep mantle history

To test whether the LLVPs could be ancient, long lived features, scientists have combined seismic imaging with numerical models that track how dense material behaves over billions of years. These models suggest that if a large volume of heavy rock were deposited at the base of the mantle early in Earth’s history, it could survive as a coherent pile, slowly reshaped but not destroyed by convection. That picture fits both the Theia hypothesis and alternative ideas in which subducted oceanic crust and other dense components gradually accumulate into the LLVPs over time.

One study on the evolutionary history of large low velocity provinces argues that crustal material was subducted, stirred through the mantle over millions of years, and then accumulated to form the LLVPs, with the African and Pacific piles acting as long term sinks for recycled rock. The same work links the Pacific LLVP to the Pacific Ring of Fire, suggesting that its presence helps organize where subduction related volcanism occurs and how plumes rise from the core mantle boundary. By treating the LLVPs as dynamic but persistent features, researchers can explain why they appear in reconstructions of mantle structure over the last 300 million years, a perspective echoed in analyses that describe how, for decades, we knew little about the protrusions under Africa, Spain, and the Atlan region, but now see them as key to understanding deep mantle evolution, as highlighted in Rese arch that explicitly ties subducted crust to the formation of the LLVPs.

Why the African blobs matter for life at the surface

The African LLVP is not just a deep mantle curiosity, it appears to be directly linked to the continent’s surface geology and perhaps even to long term climate and habitability. By lifting large swaths of Africa to higher elevations, the underlying blob may have influenced river systems, erosion patterns, and the development of rift valleys that shape ecosystems and human settlement. Its role in feeding mantle plumes could also help explain the distribution of volcanic hazards and the location of key mineral deposits associated with magmatic activity.

Analyses of Earth’s mysterious protrusions on its core argue that the African LLVP has interacted with mantle convection over the last 300 million years, helping to generate superplumes that drive large igneous provinces and continental breakup. For decades, we knew little about the LLVPs other than their locations under Africa, Spain, and parts of the Atlan region, but newer work shows that they are not the same, with the African structure more prone to spawning plumes that reach the surface. This difference has real world consequences, from the East African Rift to hotspot chains, and it underscores why the African blob in particular has become a focus of studies that treat it as a central player in Earth’s deep and shallow dynamics, as summarized in Africa, Spain, Atlan focused reporting.

From baffling anomalies to a new blueprint of Earth’s interior

As the evidence has accumulated, the LLVPs have gone from baffling anomalies to central features in a new blueprint of Earth’s interior. Researchers now describe them as enormous mantle structures that rewrite geological history, forcing a rethink of how plate tectonics, mantle convection, and planetary formation fit together. The idea that dense, possibly extraterrestrial material still sits beneath Africa and the Pacific, steering plumes and shaping continents, is a radical shift from older models that treated the deep mantle as relatively homogeneous.

One synthesis of recent work portrays the LLVPs as enormous mantle structures beneath our feet, with crustal material and possibly Theia derived rock accumulated to form the LLVPs and influence surface geology. Another overview of two massive blobs in Earth’s mantle emphasizes that they baffle scientists with their surprising properties, including their size, density, and role in organizing mantle flow, with one blob under Africa and the other under the Pacific Ocean. Popular accounts of two giant blobs lurking deep within Earth, each roughly the size of our Moon, have helped bring this story to a wider audience, while technical studies and even explainer videos on massive blobs inside Earth highlight how these structures may be responsible for some of the planet’s most dramatic volcanic and tectonic events, as seen in Deep Inside Earth, Two Giant Mantle Structures Rewrite Geological History, Earth focused summaries, Two giant blob explainers, and video discussions of how Jul level discoveries about massive blobs inside Earth may be responsible for major geological phenomena.

Why their origins still remain an open question

Despite the progress, the origins of the LLVPs remain an open and actively debated question, and that uncertainty is part of what makes the African structures so compelling. The Theia hypothesis offers a dramatic narrative in which the blobs are literally not from this world, but alternative models that rely on long term accumulation of subducted crust and chemically dense mantle components are also consistent with the data. What is clear is that the LLVPs are ancient, dense, and compositionally distinct, and that they have survived for billions of years at the base of the mantle, influencing everything from supercontinent cycles to hotspot volcanism.

Some recent reporting frames the African anomalies as colossal structures beneath Africa that may not be from this world, tying them explicitly to the giant impact event that created the Moon and suggesting that they are remnants of the planet Theia. At the same time, more cautious analyses emphasize that, though the mantle was previously thought to be relatively uniform, seismic observations now show that the LLVPs are different in both temperature and composition from the surrounding region, without committing to a single origin story. As I weigh these perspectives, I see a field in transition, with new data steadily tightening the constraints but still leaving room for competing models, from extraterrestrial remnants to deeply recycled crust, as highlighted in Scientists Uncover Two Colossal Structures Beneath Africa and in broader discussions of why there are continent sized blobs in the deep Earth that are denser and hotter than the surrounding mantle, as explored in But focused analyses.

More from MorningOverview